September 19, 1933 – September 25, 2023

The Meat Puzzle, a 2005 episode of the much-franchised US TV series NCIS, is notable for two things. One is a rare late-career appearance for Nina Foch, the Netherlands-born 1940s Hollywood star who became a noted instructor of actors and directors. The second is the moment when Mark Harmon, the show’s star, is asked what his Naval Criminal Investigative Service colleague Dr Donald “Ducky” Mallard looked like when they first met as younger men. “Illya Kuryakin,” Harmon replies.

David McCallum played Mallard for the final two decades of his life, having played Kuryakin in the hit US TV series The Man From UNCLE between 1964 and 1968. These were the years when a RADA-trained actor who had been a stage manager at the Glyndebourne opera company, had appeared on TV in Jean Anouilh’s Antigone and as US president John Adams and was soon to play Judas Iscariot for Hollywood, became an unlikely superstar and a heart-throb to match the recently arrived Beatles.

Here was a Scot, playing a Ukrainian who had presumably been trained by the Soviets before working alongside Americans in a secret international spy network. The part could have been cliched and clownish, but McCallum invested it with the enigmatic gravitas he brought to his major roles.

Like Eric Ashley-Pitt, who he played in The Great Escape, Kuryakin was resourceful, intellectual. Where his colleague Napoleon Solo (Robert Vaughn) was a Bond-esque playboy, Kuryakin was a pragmatic scientist who figured things out and was unafraid to do the dirty work.

Along with Pavel Chekov in Star Trek, McCallum’s Kuryakin was probably responsible for a thawing of American attitudes to Russians following years of cold war propaganda and high-profile espionage cases. He must have been responsible for the sales of a lot of turtleneck jumpers too.

At the height of UNCLE’s popularity, McCallum was receiving more fan mail than any other actor in MGM history – no mean feat given that Elvis Presley was also under contract to the studio. But fame had its downsides. McCallum told an interviewer: “I was rescued from Central Park by mounted police once. When I went to Macy’s department store the fans did $25,000 worth of damage and they had to close Herald Square to get me out.” It also gave him the opportunity to follow in the footsteps of his father David Sr, a classically trained musician who took up the position of first violin with the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Suggested Reading

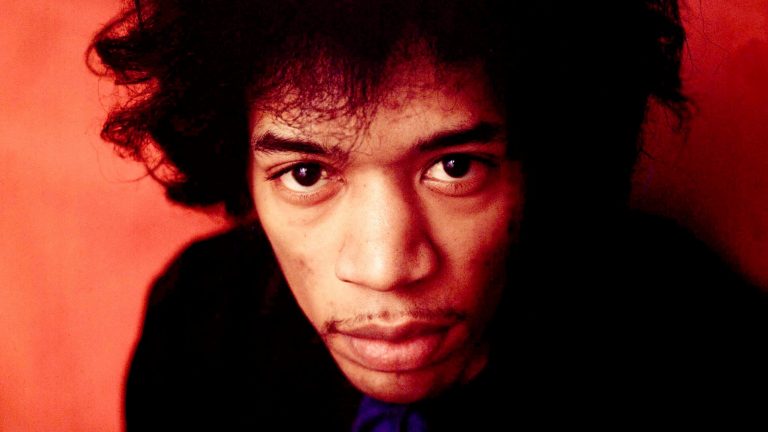

Jimi Hendrix, the guitarist who kissed the sky

In those days of Illyamania, McCallum’s name appeared on four instrumental albums produced by the gifted American David Axelrod. Music: A Bit More Of Me (1967) features the much-sampled The Edge, extracts from which will be familiar to fans of Dr Dre, the video game Grand Theft Auto IV and/or Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver.

This restless nature, this refusal to be pinned down, was one of the things that made McCallum so interesting as a man and a performer. When UNCLE ended, his choices were not those of someone devoted to retaining his status as an action TV idol.

Although he starred in a misfiring series that updated the story of The Invisible Man, he also recorded three audiobooks of novels by the sci-fi/horror pioneer HP Lovecraft and later starred as an interdimensional operative investigating breakages of time in the generally unfathomable Sapphire & Steel. McCallum treated celebrity as an impostor – “you just have to deal with it,” he said, “and then whoever was next came along, and you get dropped overnight, which is a relief.”

He was similarly pragmatic when, in an early celebrity scandal, his wife Jill Ireland, with whom he had three children, abandoned him for his friend and Great Escape co-star Charles Bronson. McCallum was left, he said, with “nothing more than a case of 1959 Chambertin Burgundy wine and a tube of toothpaste.”

He remembered it as “an extremely difficult time… But I never hated Charlie. He was always a good friend.” Indeed, it had been Bronson who, in 1963, introduced a hard-up McCallum to producers Norman Felton and Sam Rolfe at the MGM canteen. “Sam had made Have Gun – Will Travel and Norman created Dr Kildare,” said McCallum. “Now they were trying to get this James Bond-style action drama off the ground. Charlie suggested I might be right for one of the supporting roles, the guys agreed and the rest is… well, you know what.”

Perhaps this stoicism derived from his early years, where McCallum’s father was frequently absent because of work, and where his childhood meals – a “bag of bits” from the chip shop, a “jammy piece” as a treat – hardly suggest a life of privilege. Wartime brought two near-misses from Luftwaffe bombs, evacuation, and more thrift.

This might explain some of McCallum’s political views – he was a fan of both Margaret Thatcher and Donald Trump, viewed Barack Obama as both an ideologue and a socialist and believed the extent of Britain’s welfare state was hindering personal ambition in some.

Yet he knew the extent to which he was fortunate, despite personal loss that included the death of his son Jason, who was just about to become a father, to an accidental overdose in 1989.

“I could sit here and talk to you about my life and 99.9% would be wonderful and positive,” he told an interviewer in 2016. “The worst moment of my life was when I lost my son, there’s no question of that. But it’s gone, it’s done. He’s not coming back, so I don’t dwell on it. The best moment of my life is right now.”