“A graduate generation trapped and betrayed”. “The great graduate job drought”. “Will student loans be the next mis-selling scandal?” “700k graduates on benefits”. These are just a few of the many scary newspaper headlines published in the past month or two that, taken together, prompt the question: is university worth it any more?

What’s for certain is that the calculation has changed almost beyond recognition in the past two decades. It used to be a no-brainer. You got decent A levels. You went to university, preferably a long way from home. You had three enjoyable years, largely at the taxpayer’s expense. And you looked forward to a career where it was reasonable to expect that your pay would be significantly higher than it would have been without your degree.

The change began in the Blair years and accelerated dramatically during the long period of Conservative government. Over that time, tuition fees in England largely replaced state funding for university teaching and maintenance grants were replaced by loans, funded in both cases by the government-subsidised student loans scheme.

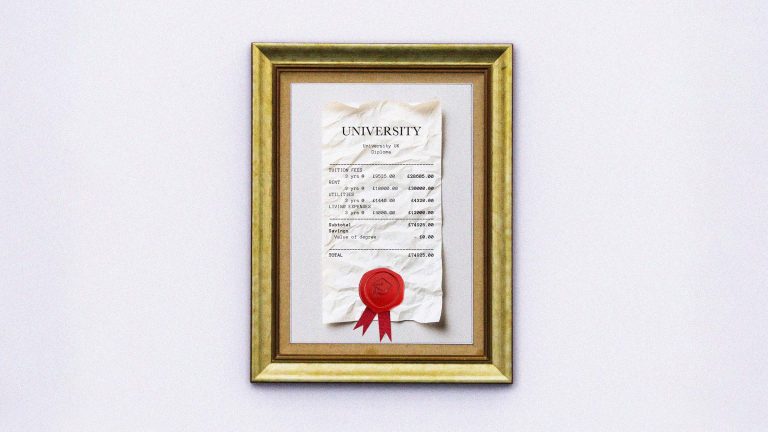

Taking both sets of support together the result was that students graduating in England in 2024 had on average outstanding loans of around £53,000 – more than double the level in 2014-15, before maintenance grants were removed. The repayment terms will be determined by how much money they make each year, and will for many students be spread out over most of their working lives.

This has had two major effects on the way students approach their university choices. One has been a very big switch in applications to courses that might lead to well-paid jobs like medicine or business and away from the humanities, the aim being to ease the repayment burden.

The other has been a much heavier demand for places in institutions that are thought to be in favour with employers – some, though not all, of the research-intensive Russell Group, or other universities with a strong record in areas like engineering.

In this changed environment, going to university is no longer the default option for students with the necessary qualifications, and the choice requires a lot more research and thought than ever before. Here are the eight questions that need to be addressed before making a decision.

Do you aspire to a job that requires a degree?

Medicine is an obvious example but there are others, for example in areas of finance, engineering or teaching. Such careers can be well paid, making loan repayments less onerous.

Are you enthusiastic enough about a particular subject to commit to studying it hard for three years?

It’s become a lot easier to get into prestigious universities by applying for the less popular courses. But that can’t be a sensible way of making such a big decision. Tuition fees now amount to £9,535 a year, and in future are set to rise at a pace to offset inflation. You must be studying a subject that you find stimulating and interesting to justify that kind of investment. All the evidence shows that the choice of the course is at least as important as the choice of the university as a pathway to future success.

Will your degree bring you economic benefit?

The answer is: it depends. Taken as a whole, graduates still earn significantly more than non-graduates over their working lives, although the size of that premium has been shrinking in recent years with the rapid growth of the graduate population.

But the average figure hides a wide range of potential outcomes. On one analysis, you were pretty well certain of getting a positive net return on your undergraduate degree in England if you studied medicine, computing or economics. By contrast, only a minority of male students gained economically from a degree in the creative arts.

This is where you need to understand how student loans in England work. If you started university in 2023 or later, you will come into what’s called Plan 5 of the repayment scheme. Under this, payments start once you earn more than £25,000 a year, and you pay 9% of your income above that threshold. Interest starts accruing from the day you start taking out a loan and is set every year on the basis of the retail price index of inflation. This year, that runs at 3.2%.

For reference, the median gross annual earnings for full-time employees in the UK last year were just over £39,000. If your earnings were much less than this, say £30,000, then under Plan Five your annual repayment would only amount to around £450 whereas accrued interest on a £50,000 loan would add roughly about £1,600 to your outstanding debt. On that basis, you would never pay off the loan, and under the Plan 5 scheme it would be cancelled after 40 years.

Things start to get much more uncomfortable for what you might call middle-income earners: somewhere between the median and, say, £55,000 a year. Your annual repayment would be much higher, but still not enough to clear the outstanding debt. So you would be paying back what amounts to a sizeable chunk of your income almost until retirement was in sight.

Once you get above that earnings figure the picture starts to look very different. Annual repayments are high, but the debt is paid off more quickly so the interest costs don’t roll up.

The bottom line is that for high earners, the student loan scheme is a reasonably helpful form of subsidised debt. For low earners, it’s the equivalent of a graduate tax. For people in the middle, it can be a heavy burden.

So that’s why the choice of course matters so much to so many students. It’s one reason why the number of undergraduates studying business and management in the UK had risen last year to 587,000, up by four-fifths since 2014-15. And it explains the steady decline in the take-up of humanities over the same period.

It’s the sad but inevitable result of ham-fisted government policy.

Which university offers you the best chance of a good career?

Once you’ve decided on the course, the next step is to choose where to study it. This isn’t just a question of going to the most prestigious institution: the best-ranked teaching in a particular course is not always to be found in the grandest universities. Employers use universities as a filtering tool in recruitment: their views matter and can easily be tracked online.

A point to consider is that according to the Office for Students 45% of English higher education providers will be losing money this year unless they take mitigating action. Some are already laying off large numbers of faculty members. Better to go to somewhere that’s thriving rather than somewhere that isn’t.

Suggested Reading

Is 2026 the year that Britain’s universities go bankrupt?

You can judge the way students are working all this out by looking at the way student numbers are changing in particular institutions. Overall acceptances this year rose by 2%. The Russell Group had a 9% increase, but this was heavily concentrated in half a dozen universities – UCL, York, Queen Mary, Durham, Warwick and Exeter, all of which had increases of 20% or more.

Elsewhere, places like Bath Spa and Wolverhampton saw big increases. But several other less-favoured institutions registered steep declines in acceptance rates.

How will you pay for your living expenses?

The best answer is to have well-off parents. But if they are not available, you have to turn to student maintenance loans. Under the government scheme, most students can borrow an amount each year which is based on their family household income, whether they live at home, and whether they study in expensive London. For someone living away from home and at a university outside London, the maximum entitlement this year is just short of £11,000.

In real terms, this figure has declined significantly in the past decade, partly because of higher-than-expected inflation and partly because the government has frozen the threshold for household incomes that determines how much can be borrowed.

This explains why large numbers of students now live at home, rather than study in distant cities, and why so many students have had to take up part-time jobs in order to make ends meet. A recent analysis by the Higher Education Policy Institute found that, in a study of four universities, two-thirds of students were working part time to cover their living costs, and on average were doing 50-hour weeks when study and travel time were also taken into account.

That’s a long way from Brideshead Revisited.

The government has promised to restore maintenance grants to students from disadvantaged backgrounds in as yet unnamed priority subjects. But these are unlikely to be on a scale to be game changers.

What if you really want to study a subject that seems unlikely to lead to a well-paid job?

Go for it – but do so with your eyes open. Get to understand the fine detail of the loan scheme. Do all the homework you possibly can.

Where you want to live after university will make a difference: life is a lot cheaper outside London. And no-one – least of all the government – knows where the jobs of the future lie. AI firms are hiring philosophers to help them grapple with the ethical issues thrown up by their technology. Software companies need anthropologists to understand how their kit might be used. We’ll always need poets.

What are the realistic alternatives to a university degree?

There are quite a few, but they are fragmented and depend in some measure on where you live. Higher and degree-level apprenticeships are an attractive option for people who want practical paid-for learning, but they are not available in huge numbers. Some of the big accounting firms are taking on school leavers and teaching them the tools of the profession. More employers are saying that what matters to them is attitude, rather than degree qualifications.

But it can be a risky path. Unemployment rates are lower for graduates. According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies, women without a degree find it harder to get a well-paid job than do men. And people from disadvantaged backgrounds find it much harder to get a good income if they don’t have a degree.

Will AI destroy the value of your degree?

That’s been a popular newspaper scare story in recent months as early-career employment has been squeezed at the same time as AI has taken off. In fact, this correlation looks dodgy: the pressure is more likely to have come from interest rate changes and economic uncertainty than from ChatGPT.

Consultancy firms have a happy time forecasting massive disruption in the labour market, but the reality is that no one knows when, whether, or how AI will have a real impact. The best bet surely is to assume that in a knowledge-intensive society an ability to think critically will be more important, not less.

Suggested Reading

The great university rip-off

The bottom line is that even in today’s very different environment, the student experience is about much more than building economic value. It’s also a time for developing intellectual and social capital, for learning new ideas and making new friends. Despite all the gloomy headlines, few graduates regret going to university – around 8% in a recent survey. And far fewer students drop out of their course in the UK than is the case in other developed countries.

So yes. Provided you go in with your eyes open and understand that the university world has changed dramatically in recent decades: provided you choose the right course in the right university: provided you recognise that one way or another you are going to have to pay for most of the benefits of your education – then university is still well worth it.

Richard Lambert is former editor of the Financial Times and chancellor of the University of Warwick