A choppy green ocean flecked with white, and a massive, black-hulled ship surging through it: an undeniably romantic maritime image. One of thousands now circulating online, it depicts the last days of the liner the United States, on tow from Philadelphia to Florida in September, to its planned sinking as an artificial reef.

The last liner built for the long-defunct United States Lines (USL), the United States was an American icon, and its numerous celebrity passengers included Marilyn Monroe and Salvador Dalí. In the late 1960s, as a baby, I was one of its final passengers.

Suggested Reading

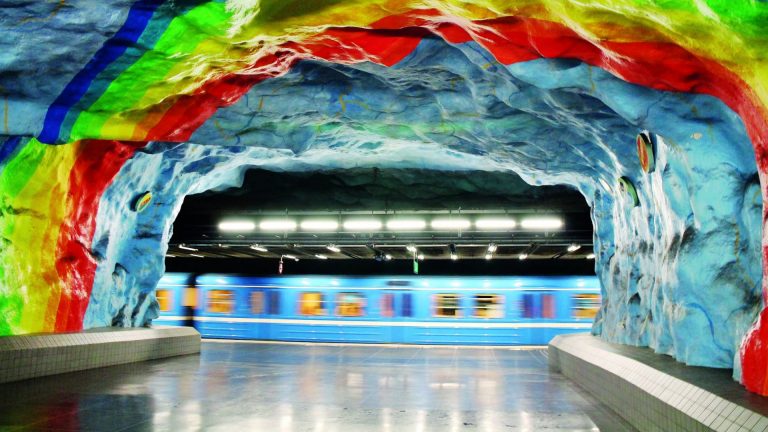

Tunnel visions: The world’s most beautiful subway stations

In its pomp, the United States was also by far the fastest ship on the Atlantic. It won a prize in 1952, the Blue Riband, for the fastest Atlantic crossing, at an average of 35 knots, or over 40 mph. It was reported by the New York Times, although never proved, that it was capable of 42 knots, or nearly 50 mph – imagine an object the size of the Empire State Building travelling at close to motorway speeds.

It often shows up in popular culture. There’s an aerial view of it in the opening sequence of the 1961 West Side Story movie, where it looks like a dagger aimed at lower Manhattan’s gridplan.

The United States was a national symbol, as were all Atlantic liners. However, it was more than merely symbolic, as it had been designed specifically as a troop ship, capable of moving a 14,000-strong army division at speed from the United States to Europe.

Funded equally by USL and the military, it was built in a naval rather than civilian shipyard at Newport News, Virginia. The design of its hull remained secret for decades (toy replicas, including mine, stopped at the waterline).

Other liners of the time had played a military role, like Cunard’s ships during the second world war. But they were fundamentally civilian, whereas the United States was conceived by the military for war purposes. And it looked it – its utilitarian interior was almost almost entirely wood-free as a wartime fire prevention measure (the only wooden items, it was said, were a butcher’s block and a grand piano).

Outside, the beetling superstructure and the two huge smokestacks gave it a battleship-like profile. Compared with today’s cruise liners which look exactly like what they are, floating resort hotels, the United States was built for speed.

Despite its iconic status, the United States had a strange life. It only saw active service for 17 years, retiring abruptly in 1969 when United States Lines declared passenger traffic economically unviable. It passed into navy ownership until 1978, hermetically sealed in a Virginia dockyard, in theory ready for action. It then had a succession of owners, all of whom failed to bring it back to commercial service.

In 1992, it made a last eastbound transatlantic voyage to Turkey, and then Ukraine where in Sebastopol it spent a couple of years having its asbestos stripped, a job apparently too hazardous for Americans. It was towed back to the US in 1996, where it found a berth in Philadelphia for the next 29 years.

It became a niche tourist attraction in Philly. If you visited the local Ikea, you looked out on it as you ate your meatballs – right across the street from the furniture store, it filled the view from the restaurant windows.

For its 73 years of existence, it spent no less than 55 of them inactive, latterly as a semi-ruin overseen by the SS United States Conservancy, a charity engaged in increasingly desperate attempts to secure the ship’s future. It was an odd life for such an icon. We tend to think of these liners as eternal, but scarcely any of them actually survive.

Back to the present day: following a choppy voyage under tow along the US east coast, the United States arrived in the deepwater harbour at Mobile, Alabama, having been sold to Okaloosa County, Florida. At Mobile, it lost its signature funnels to a proposed museum, along with anything non-metallic from the interior. At some point to be determined in 2026, the ship’s eviscerated remains will be scuttled to make what the Okaloosa County trumpets as the “world’s largest artificial reef”, a magnet, it is hoped for tourist divers – and fish.

I was a baby when I travelled on the United States, and while I have no memory of the trip, it loomed large in my childhood. My parents had saved postcards of the ship at speed in a turquoise Atlantic, deck plans, luggage tags, menus, a cutaway drawing showing off the different parts of the ship – I spent hours absorbed in them.

For my parents, and I am sure countless other passengers, the United States represented a benign and generous America, of fine engineering and public works. They spoke of it in the same way they described other things they had liked about their stay in the country: national parks, clean campsites, fine roads and decent plumbing.

Above all, the United States was Atlanticism – perhaps in its most literal form. A projection of American cultural power, it was perhaps the maritime equivalent of Encounter magazine, or Radio Free Europe. Its America was relentlessly optimistic and progress-oriented, represented in the ship’s unfussy, fresh interiors. You see it in USL’s zippy advertising from the 1950s – this was the modern ship, unlike its British rival, Cunard’s stuffy Queen Mary.

The United States was also, underneath it all, hard power too. This was the ship that might, after all, be called on to save Europe. For those good historic reasons, during 2018 the SS United States Conservancy approached President Trump to see if he might help save it for the nation, perhaps as a patriotic tourist attraction on New York City’s West Side, where there are other historic vessels including the USS Intrepid, a second world war aircraft carrier. He declined.

We understand much better in Trump’s second term quite how far Atlanticism is down the toilet. There will be perhaps no better symbol of its new status than the scuttling of the United States.

Richard J Williams is the author of Imaginary Cities: The Expressway World (Polity)