Like many a young, radically minded artist of the 1920s and 30s, Cliff Rowe railed against capitalism and fascism. He was a pacifist, an idealist, who believed he had found the panacea to the world’s evils in The Communist Manifesto, written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

“It solved so many intellectual problems,” he wrote. “I felt the scales drop from my eyes.”

With his lover, he set sail for the Soviet Union in May 1932, where he exhibited vast canvases for the 50th anniversary of the Red Army in support of the “international solidarity of the revolutionary detachment of the world proletariat”. The paintings showed English workers striking for better conditions being brutally assaulted by truncheon-wielding policemen.

By late 1933, he decided to return (with a new wife) to England, where “the class struggle was really going on”. As the historian Andy Friend records in Comrades in Art: Artists Against Fascism 1933-1943, his first call was to a friend, the designer and architect Misha Black, only 23, who was renting office space above a shop in Seven Dials, central London.

It was there that Artists International was born, its purpose defined by artists who were not particularly well known at the time – and perhaps not very familiar today – such as Pearl Binder, James Fitton, James Boswell, James Holland, as well as Rowe and Black. They were united by their own poverty, reeling like the rest of the country from the Great Depression, which they blamed on the iniquities of capitalism but, above all, unanimous in their resolve to oppose the rising tide of fascism in Europe inspired by Mussolini and Hitler and, later, Franco.

Communism, however, as espoused by the Soviet Union, remained their lodestar, guiding them to a society that was free, equal and peaceful. Their philosophy was recorded at that first meeting in Seven Dials by 16-year-old Edith Simon, the daughter of a German refugee, who worked as odd-job girl and copy-taker for 10/6d a week (about 12.5p today).

“Can you imagine the upsurge of energy and will from the news that art could actually help to revolutionise society?” typed Simon. “Clearly artists formed the natural vanguard in the fight for peace, freedom and full employment.”

The gathering had somewhat clunkily called themselves The International Association of Artists for the Revolutionary Proletarian Art, but she added in the margin “Artists International – British Section, more generally called AI.”

Friend has filled the book with considerable detail about their work, their loves, marriages and divorces, as well as acknowledging the contributions made to the cause by influential artists not just from Britain but also the USA, Mexico and Europe.

Their primary means of raising awareness – and money – was by staging exhibitions. The first, The Social Scene, was a mixture of Marxist discussion group and agit-prop, festooned with anti-war and anti-fascist posters. It showed works by artists such as Edward Burra, Henry Moore, Eric Gill and Paul Nash. A snatched photograph by Edith Tudor-Hart of three distinctly shifty surveillance officers on the lookout for troublemakers at a Communist Party rally in Trafalgar Square is a reminder of the hostility AI faced from the establishment.

AI kept up a steady flow of articles in publications such as the Left Review, designed posters and book covers, printed satirical cartoons, but perhaps their coming of age as an effective protest group was the exhibition held in Soho in 1935, Artists Against Fascism and War, which attracted Laura Knight, Augustus John, Duncan Grant, Nash and Moore. Just as significant, given the group’s international aspirations, it also featured more than 30 contributors from France, including Fernand Léger and André Lhote.

Further exhibitions were staged, one in the Charing Cross underground booking hall, which featured a painting of blazing rooftops after an air raid (Incendiary Bombs, Old Camden Studios) by one-time copy-taker Edith Simon, and another on the bombed site of John Lewis on Oxford Street.

The group rarely faltered in their support of the Soviet Union, but that was jolted in 1939 when Stalin allied with Hitler. There was considerable relief when Hitler turned on Stalin, enabling Britain and the USA to join forces with the Soviet Union. The AI committee sent greetings to the artists of the Soviet Union “withstanding fascist attack on civilisation” and welcomed “all possible cooperation in the common task”.

For all the rhetoric, the political ins and outs, the original band of comrades who gathered in Black’s scruffy flat in the autumn of 1933 stayed true to their own recruiting leaflet: “The artist must be on the side of the working class.”

Boswell produced satirical drawings of the effete upper classes, and his dense lithographs in The Street are likeable, thoughtful reflections of London. His series Bull, however, is a savage indictment of the officer class and their callous treatment of their men. It is hard to look at two officers with bulls’ heads forcing a cross down a soldier’s throat.

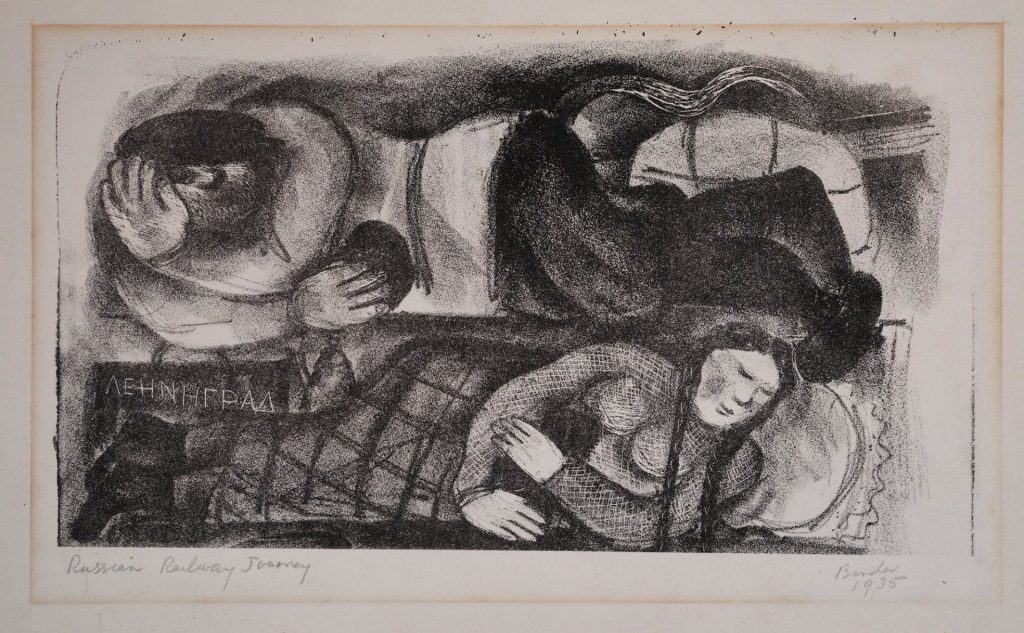

Binder produced warm-hearted lithographs of Jewish life in the East End, a bookshop, restaurant and the hustle and bustle of the evening crowd in Aldgate.

Fitton painted forceful propaganda posters and had an eye for satire; For Charity has a group of well-fed types doing their bit for a worthy cause by gathering around a table overladen with food and wine.

Suggested Reading

The water always wins

Rowe, the man who got the ball rolling when he contacted Black in 1933, is perhaps the foremost of the group. He painted accessible scenes of working life, but the ferocity of his anti-establishment feelings is palpable in his posters, none more than Jubilee (1935), which shows a skull with a crown, a dribble of blood from his jaws. The poster reads “25 years of war, hunger and unemployment”.

Oddly, it is one of the quieter paintings, The Fried Fish Shop (1936), that says as much about the group’s loyalties as the more strident works – and something about Rowe’s sense of humour. Customers in a cafe are enjoying that most quintessential of British meals. A sign reads “Harry’s for Quality” and the man serving the fish and chips is Harry Pollitt, leader of the British Communist Party. A man in a bowler hat is a detective checking up on possible sedition.

Perhaps he had his eye on the solitary figure at a table in a blue coat and distinctive cap. None other than Joseph Stalin himself.

Comrades in Art; Artists Against Fascism 1933-1943 was published on September 4 by Thames and Hudson, £40

Richard Holledge writes about the visual arts for the Wall Street Journal, Gulf News, Financial Times and The New World