What to do when you are faced with a half-mile walk along a muddy country lane at night, in one hand an armful of crucial paperwork, in the other a painting by, er, Cézanne?

That was the predicament facing John Maynard Keynes, towering intellectual, economic adviser to governments, but no athlete. No way could he carry both all that way, so he came to a pragmatic decision; he ditched the Cézanne. Quite literally. He hid the painting behind a hedge and hurried to Charleston Farm, the country retreat of the Bloomsbury Group, where his friends Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant were waiting for him.

Keynes, who was serving in the War Office, had been urged by his occasional lover, the artist Duncan Grant, to go to Paris with the director of the National Gallery, Sir Charles Holmes, to buy what they could from the collection of Edgar Degas, who had recently died.

Never mind that it was 1918 and war was raging, with the sound of guns echoing across the city. In what reads like an episode from Carry On Up The Gallery, the odd couple sailed to Boulogne and on to Paris by train with £20,000 in French banknotes. To appear French and more acceptable to prickly Parisian auctioneers, Holmes shaved off his moustache, wore glasses and adopted a French accent. It seemed to work – they picked up some genuine bargains.

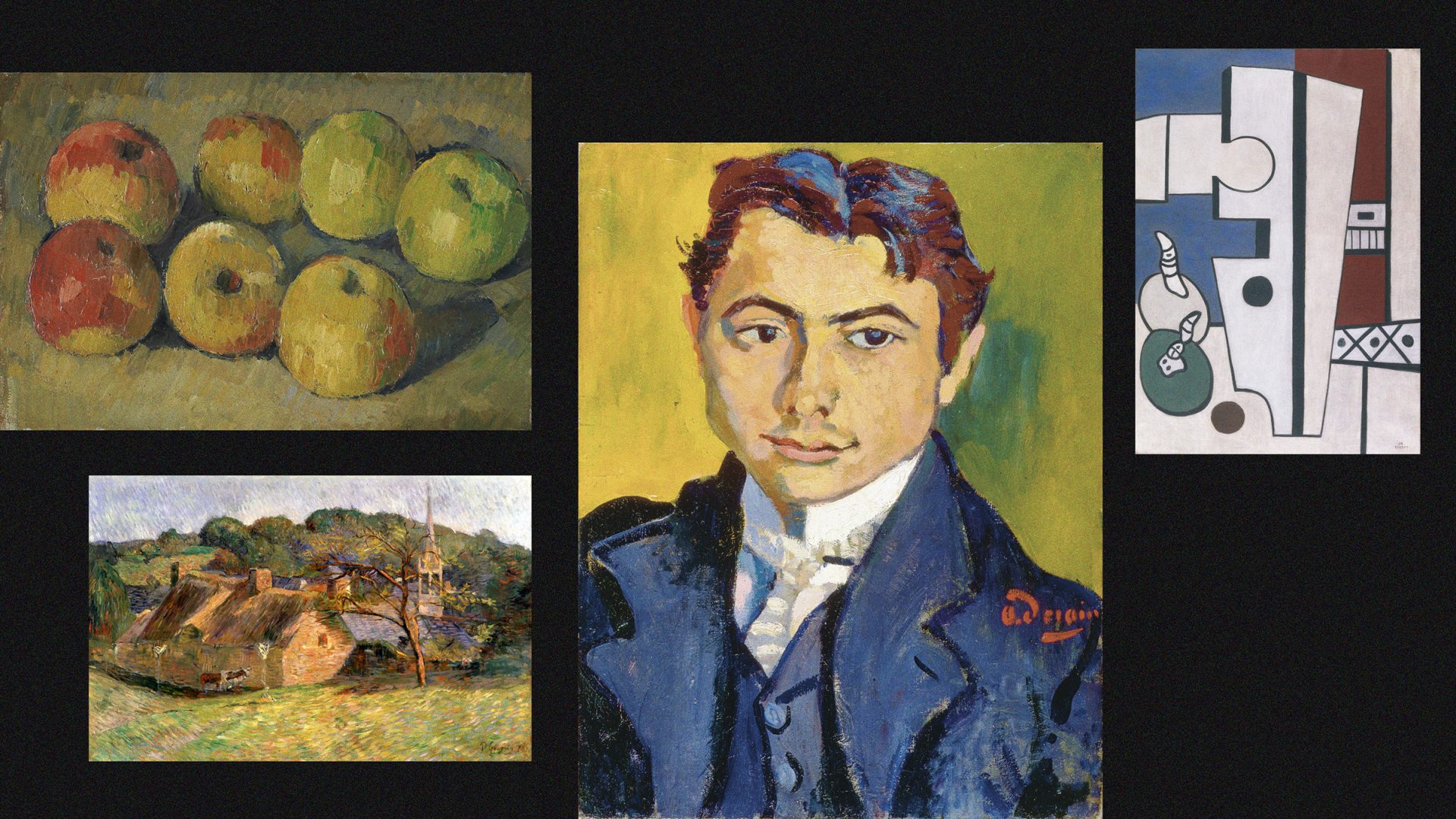

Keynes’s eye was caught by a charming Still Life with Apples (1878) by Cézanne, which he bought for himself for £500, bringing it home on the ferry to Folkestone, where he was given a lift as far as the lane to Charleston.

Once rescued from the hedge, Keynes kept the painting until his death in 1946, when it was bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Today it hangs in its luminous beauty for the first time in more than 100 years as the centrepiece to Inventing Post-Impressionism: works from the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, an exhibition at Charleston in Firle of works from the Birmingham gallery while it undergoes renovation.

It is a slight show but one that celebrates two seminal exhibitions staged by another Bloomsbury stalwart, the art critic, designer and curator Roger Fry. The first, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, at London’s Grafton Gallery in 1910, celebrated the works of the French Impressionists who were all but unknown in Britain.

Fry was obsessed with them, particularly Cézanne, whom he admired for his experiments with colour and form, and Van Gogh for his emotional freedom. In the introduction to the catalogue, he wrote how the works of the Impressionists were “less about the accurate depiction of, say, a tree and more about the tree-ness of the tree itself”.

Aware that many gallery-goers would be baffled by this concept of tree-ness, not to mention the bold colours and unruly imagery on display, Fry gave top billing to Édouard Manet. He was eager not to shock the public with anything too radical at the beginning of the show and considered that the artist was a familiar, accessible figure, who would ease the viewers past the exhibition’s startling paintings to the most disquieting of them all, Matisse. One observer remarked that the progression to Matisse was a shock “administered by degrees”.

The key word for the Charleston exhibition is inventing. It was an exercise in shrewd marketing by Fry to coin the term Post-Impressionists for the first time and thereby define the group as if they were part of an actual movement, even though the Impressionists did not refer to themselves by that label – and, anyway, by that time most of them were long dead.

It worked, with 25,000 flocking to the show over two months and reacting with fascination and horror, but mostly horror.

The critics hated it. Paintings such as Cézanne’s Madame Cézanne in Armchair, Matisse’s The Girl with Green Eyes, Gauguin’s vivid self-portrait as Jesus in Christ on the Mount of Olives and Nude Girl with a Basket of Flowers by Picasso were damned as “bizarre, morbid, and horrible”.

Critics dismissed the works as “paint run mad” and like a “gross puerility which scrawls indecencies on the walls of a privy”.

Undeterred, or maybe encouraged by such a succèss de scandale, Fry held the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition two years later, in 1912. The catalogue cover had the face of a woman drawn by Duncan Grant with a hand raised in defence, perhaps in anticipation of further negative reviews.

This time, the public was more receptive. As well as Cézanne, Gauguin and Matisse, there were seven Picassos and a room showing the “modern” work of up-and-coming British painters such as Wyndham Lewis, Grant, Bell and Henry Lamb.

The violent dashes of colour, the “primitive” imagery, the display of the body so antipathetic to Victorian sensibilities, the puzzling innovations by such as the Fauvists, were undoubtedly a threat to the art establishment and proof of the artists’ “psychological degeneracy”, but they were catnip to younger artists.

Bell declared that the exhibition provided a “freedom and release” with the “graphic, vibrant, and sensual French compositions an antidote both to the oppressiveness of technical finesse, and to the dark palettes of Victorian-era aesthetics.”

The Charleston show captures some of that spirit, with works that echo the paintings exhibited by Fry. The originals have long been dispersed to private and public collections around the world.

The names are so familiar and their work so recognisable that it is hard to grasp the furore the two exhibitions excited.

Renoir, Pissarro, an uncompromisingly angular oil by Fernand Léger, a tender lithograph by Vuillard of his sister hunched over her work in The Dressmaker, the blood red and tormented flesh of The Crucifixion by Odile Redon, a sweet glimpse of family life in The Evening Meal by Pierre Bonnard.

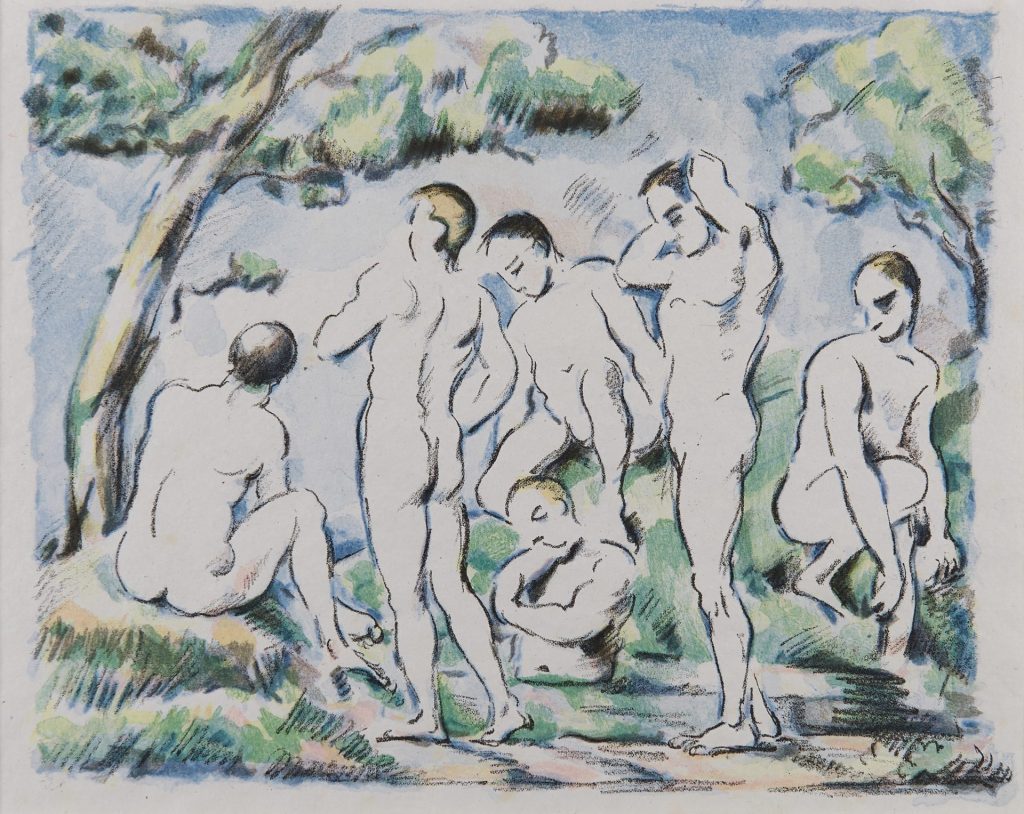

The Bathers by Cézanne displays the kind of uninhibited nakedness that no doubt endorsed the critics’ opinion in 1910 that the artists were guilty of “sexual perversion and moral depravity”.

The drab colours of an early Van Gogh, A Peasant Woman Digging, capture the back-breaking struggle to eke a living from the soil. Quite a contrast to Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows, which was shown at the first show and described as the “visualised ravings of an adult maniac”.

Of all the Impressionists, Cézanne was Fry’s hero, and his enthusiasm for the artist was gently mocked in a series of watercolours by Henry Tonks, a surgeon turned painter. In The Conversion of St Roger he portrayed Fry on his knees in the divine presence of Cézanne, while in another, Fry lectures to a group of fellow artists holding up a dead cat while art critic Clive Bell is shown ringing a bell and shouting Cézannah, Cézannah, rather than hosannah.

Despite this wry assessment, Fry succeeded in changing public perception of what art could and should be, and hugely influenced the artists of the day. Thanks to the two exhibitions, he is recognised as a champion of modernism, the movement that rejected the claustrophobic mores of Victorian art with its formal strictures and dour imagery and replaced it with freedom of expression, a liberation of art and lifestyle.

No wonder Virginia Woolf, that most eloquent of the Bloomsbury Group, declared after the first exhibition: “On or about December, 1910, human character changed.”

Inventing Post-Impressionism: works from the Barber Institute of Fine Arts is at the Charleston, Charleston in Firle, Lewes until November 2