It concentrates the mind no end when a visit to an art gallery is disrupted by a rather long snake slithering briskly across your path. “Can be deadly,” said the guide casually as the creature disappeared into the undergrowth.

It was an unexpected sideshow even for the Instituto Inhotim, an eye-opening array of contemporary art set in a parkland of dense tropical forest, lagoons and grassy meadows, paths bedecked with vivid orchids.

Inhotim is spread over 345 acres in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, some 300 miles north of Rio de Janeiro and one hour’s drive from the nearest city, Belo Horizonte. It boasts 24 galleries, some dedicated to well-known Brazilian artists such as Adriana Varejão, Cildo Meireles, Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape, as well as several of international renown such as Olafur Eliasson and Yayoi Kusama

This fabulously eccentric project is the creation of the immensely wealthy mining magnate, Bernardo Paz, who bought a farmhouse in the area in the 1980s where he could show his growing portfolio of art. Paz went on to acquire about 2,500 acres, and with the advice and friendship of Tunga, one of Brazil’s most famous artists globally, opened his collection to the public in 2006.

Appropriately, perhaps, Tunga’s work is celebrated in the park’s biggest gallery, with sculptures made from materials such as glass, heavy skeins of rope, felt and rubber. In True Rouge (1997), for example, nets filled with glass bottles, beads, and red fabric is a curious mix of scientific experiment and mystical ritual.

His often puzzling works stand in stark contrast to Paz’s hard-edged commercial world – he made his fortune in a region where 17th-century Portuguese colonists were drawn by gold, and which today boasts a booming iron ore and aluminium industry. Open-cast mines scar the hillsides, yet without the wealth they have brought to the region, the green oasis of Inhotim would not exist.

Culture and business clashed in 2018, when Paz was accused of illegal deforestation, land grabbing and using slave labour, and sentenced to nine years in jail for money laundering. Though he was cleared in 2020, he no longer plays a part in the institute, which is run by a private non-profit organisation with a board of directors.

One of their earliest challenges came in January 2019 when a dam burst and destroyed the town of Brumadinho, only three miles away. Tragically, 270 people died and six are still listed as missing. To assist the town’s recovery, they started education courses for local people and recruited many to drive the park’s golf carts and trained others as guides.

It is a joyful representation of the town which greets the visitor. Two vast 3-D murals created by John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres show a big blue bus full of passengers on one wall arriving at the terminal to find a party in full swing with people dancing to forró, a traditional form of Brazilian music, while on the other, a jaunty African religious cortege parades along to the beat of the drums.

To illustrate the connection between the town and Inhotim, our guide was eager to share that the pregnant woman in one scene is a family friend and showed us a picture of her today with her baby.

There is a lot to see. Golf carts whizz visitors to the furthest points, but by walking there’s time to see dramatic blue butterflies, lizards, tiny monkeys and flashy toucans. There is something delightfully serendipitous about coming across a gallery half-hidden by foliage or spotting an outdoor sculpture through the columns of the slender trunks of the Tamboril tree.

da cor, Penetrável Magic Square #5, De Luxe, 1977

The gallery dedicated to Lygia Pape is one of those almost lost in the greenery. As one of the proponents of Brazil’s Concrete movement of the 1950s which espoused clear, hard shapes, it is only fitting that her work is housed in an uncompromising concrete structure.

While much of her early work was all very rational, here, Ttéia 1, a Portuguese pun on teia (web) and teteia (something or someone of grace) – is altogether more emotive. Shimmering golden threads stretch from floor to ceiling and from corner to corner, seemingly weaving through the air. It is a work of apparent simplicity and of great beauty.

Just as spiritual, Forty Part Motet by Janet Cardiff. She recorded 40 members of the Salisbury Cathedral Choir singing Thomas Tallis’s 16th-century choral composition In No Other Is My Hope and has arranged speakers in eight groups of five singers, from soprano to bass. The listener can move from speaker to speaker to hear individual voices or stand in the middle to hear the sounds in unison.

You then emerge blinking into sunlight to find three VW Beetles painted in red, blue and yellow by Jarbas Lopes to celebrate a long drive the artist and a group of friends took in 2002. On their travels, they fastened stickers featuring palindromes to the windscreens of random cars and the game is repeated here. One example reads: e nobreza fazer bone (in English “and nobility to make a cap”). Something lost in translation, maybe.

Still, whatever it’s all about, the three Beetles make you smile, which cannot be said of the work by Brazilian conceptual artist Cildo Meireles. His works are often angry responses to oppressive regimes such as the military dictatorship which afflicted Brazil from 1964 to 1985.

In one, he takes an everyday family room with its tables, chairs lamps, a birdcage, telephone, all the impedimenta of daily domesticity. Every item is painted red. The effect is uncomfortably claustrophobic, but a small red sauce bottle which has spilt its contents on the floor leads to something altogether more disturbing – a darkened room. In it a sink, slightly tilted. Blood runs from a tap.

His work is fiercely political, so too that of Adriana Varejão. One of her sculptures in the gallery, Linda do Rosário (2004) refers to a hotel in Rio which collapsed in 2002.

All escaped save for two lovers, both high-profile in city society and about to be married – but to other people. To flee the building might find them being recognised, and a scandal would erupt. They stayed, only to perish in the rubble. Varejão’s interpretation is an unflinching mess of blood and guts trapped within the ruins.

Many of the artists reflect on Brazil’s troubled history, not least the shame of the slave trade. Grada Kilomba has filled a huge space with O Barco/The Boat, in which 140 blocks of burnt wood, each in the shape of a coffin, are arranged to represent the outline of a ship. Each coffin carries a saying in six languages, including Nigerian Yoruba, Portuguese and English. One reads, “One Sorrow, One Revolution”, another, “One Boat One Cargo Hold”.

Paulo Nazareth also speaks to the country’s sense of identity by travelling around the country painting scenes which seem simply to be of everyday life, but are a recognition of those who are dispossessed and who stay out of sight because they have legal problems or are being harassed by the authorities.

To imbue outsiders like them with a sense of dignity, he has assembled medals to honour the memory of indigenous and black leaders who resisted European colonial domination. His citations include Haiti revolutionary leader Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Jamaican insurgent Nanny of the Maroons.

The struggles of the Yanomami, an indigenous people living in the Amazon rainforests to preserve their identity against the often violent opposition from white people, are forcefully portrayed in 400 photographs by Claudia Andujar. She not only campaigned for their rights but her images, often close, unflinching portraits, speak of the tribespeople’s pride and a determination to survive.

Suggested Reading

Gaza and a dance against oblivion

If most of the artists are from Brazil – or about Brazil – it is Japan’s Yayoi Kusama who draws the longest queues. Visitors are allowed only two minutes to appreciate the apocalyptically titled In Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity (2009), with its flickering pinpricks of light that brighten and fade to complete darkness with hypnotic effect.

But for all her cleverness, for all the committed, often angry works, the greatest pleasure is to wander through groves of Jacaranda and mango trees, crick your neck looking up at the Bismarck Palm with its silver-blue foliage or the towering Talipot Palm topped by a fringe of yellow flowers like a bad haircut. And orchids, orchids all the way.

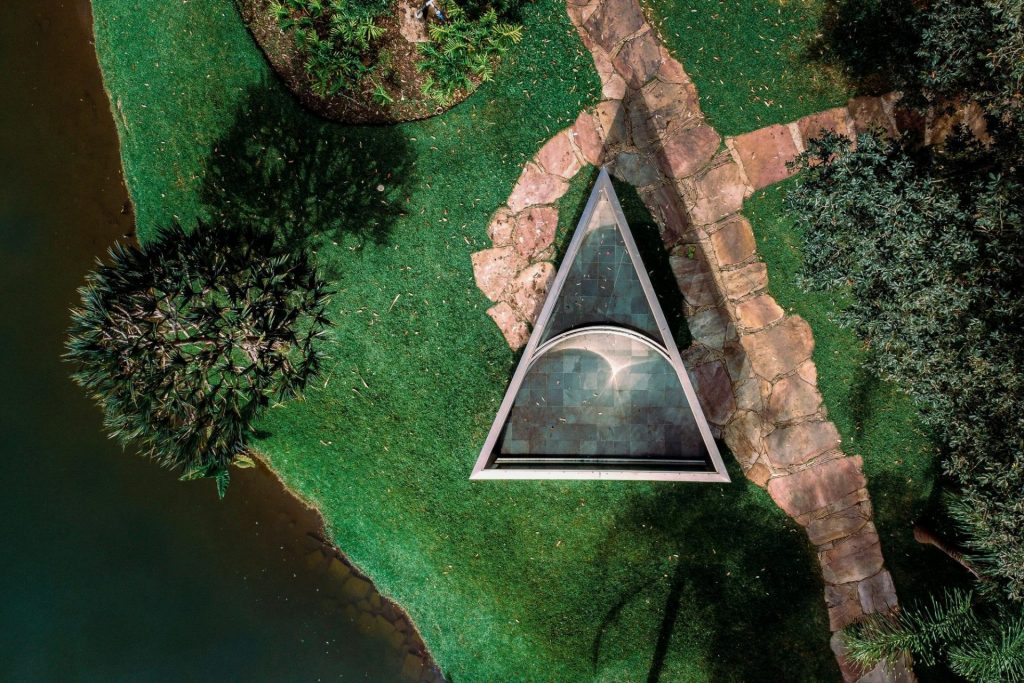

Across a lake and through the trees, the pink, blue, red and yellow panels of Hélio Oiticica’s impromptu gathering place Magic Square #5; in a glade, the distinctly odd trio of somersaulting headless bodies in bronze by Edgard de Souza, the rusty steel beams of Chris Burden’s Beam Drop Inhotim stand starkly on a hillside, and to cheer everything up, a bright yellow duck made by Paulo Nazareth, bobs gently on a lake. Well, why not.

As if there weren’t enough trees, Italian Giuseppe Penone has made one of bronze cast from a mould of a chestnut found in the grounds of Versailles, Paris. In Elevazione (2001), the bronze is raised on steel supports three metres above the ground and set among five (real) trees.

The tree is quite a walk from the park’s front gate but it’s worth it, especially when a toucan flaps languidly past and lands on its unyielding branches. Altogether more appealing than a snake.

Inhotim is open Wednesday to Sunday, tickets £11 (free on Weds). Tour operators offer day trips from Belo Horizonte (you will need at least one day to get the most out of the place). The expensive Clara Arte Hotel is on the doorstep but other hotels are available in Brumadinho