On the day Augusto Pinochet seized control of Chile, primary school teacher Paz Errázuriz climbed up to the top of her house in the Santiago suburbs. Above her were screaming jet fighters; in the distance she could see smoke billowing from the blasted ruins of the Presidential Palace.

It was September 11, 1973. The coup ushered in 17 years of dictatorship during which thousands of dissenters were killed, many more tortured and at least 40,000 “disappeared.” That “terrible” day spelt the end of her teaching career because she belonged to a union but was determined to do what she could to undermine the regime. She decided to become a photographer.

She had no training – “I did not know what I should be doing” – but the mere fact that she was a woman, on the streets of the capital, with a camera of all things, was itself a form of resistance.

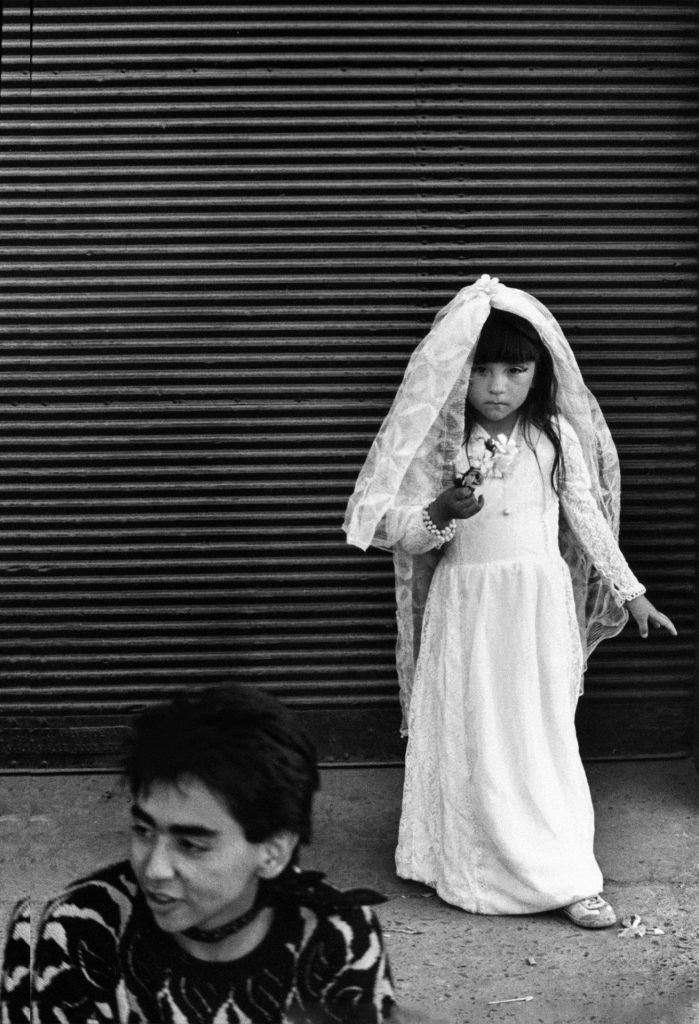

Errázuriz, 81, found her subjects on the margins where transvestites endured persecution, where prostitutes plied their trade and psychiatric patients were treated with a cruel disregard. Their images, often defiant, often proud, many inscrutable, line the walls of the MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, in a comprehensive exhibition covering more than 50 years of her work, Paz Errázuriz: Dare to Look; Hidden Realities of Chile.

“People talk about outsiders or minorities but for me they are not outsiders,” she says. “It’s just that the margin is where power looks differently. These are people who stand outside and have always been subordinated to power. You have to make people learn how to look.”

With no one to tell what to do she developed her own mantra – “No studio shots, no flashes, no unnatural poses. Chile. Always Chile” – and produced portraits of unusual candour.

One of her earliest photographic essays, Dormidos (The Sleeping, 1979) expresses the nihilism felt by many at a time when 45% of the population lived below the poverty line and unemployment had risen to 30%. Men are slumped in doorways or balanced precariously on walls and benches, some are drunk, all without hope. In an impromptu moment Errázuriz photographed a drunk reeling down the street from the window of her car. It is a rare flash of playfulness.

She turned her gaze on the elderly in her series Old Age (1983) with results which are humorous and empathetic. One group seem to be dressed for a beauty pageant and in another slightly surreal gathering, women pose stoically in bonnets, some in tiaras, others clutching dolls. Most moving, Asylum (Woman and Nun, 1986) in which a nun gently massages the feet of an old lady.

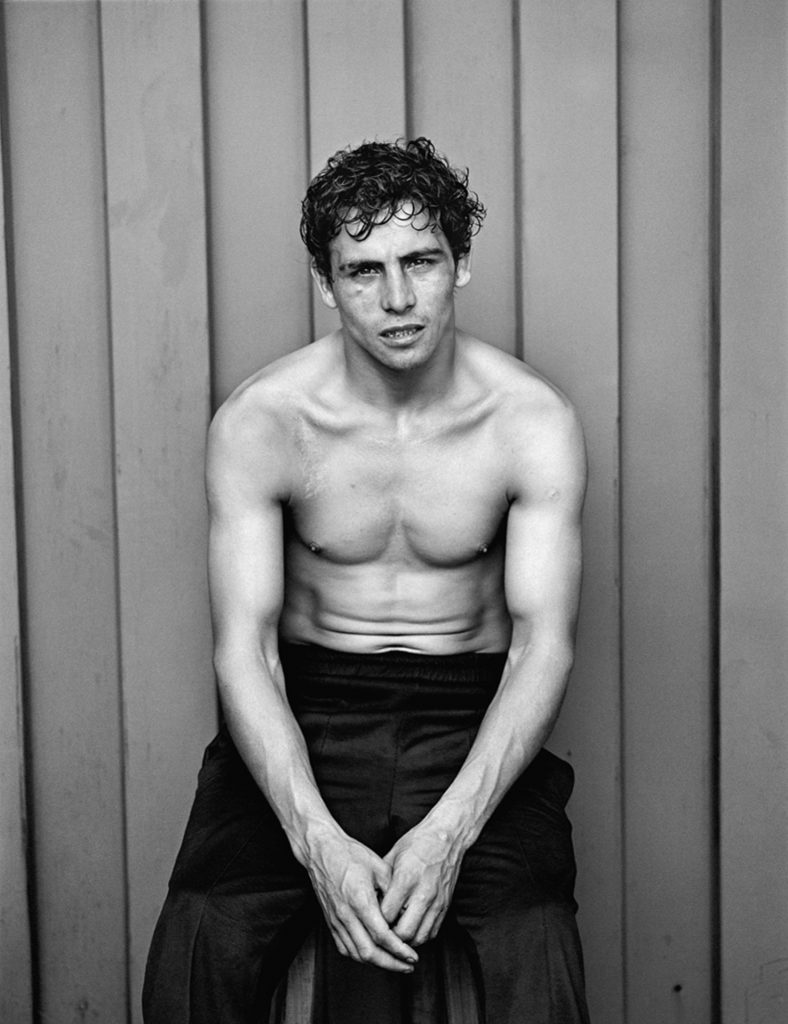

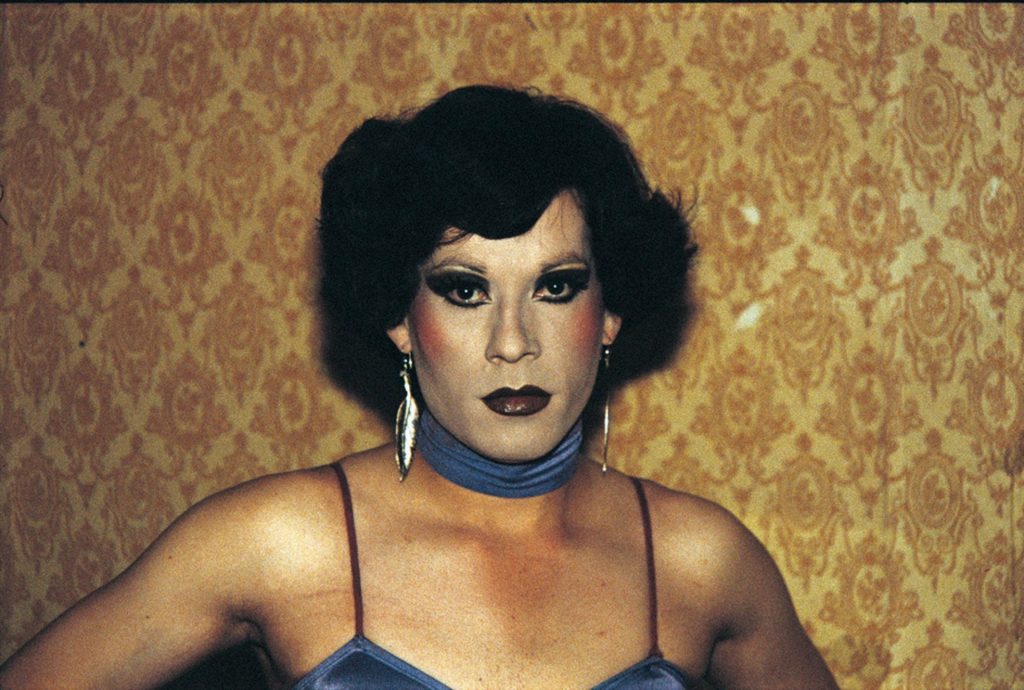

The combination of her gentle demeanour, obvious compassion and unshakeable resolve is evident in the series Adam’s Apple (1983-88) which follows the lives of transvestites. She spent more than four years earning the trust and friendship of what was a paranoid community. Understandably; homosexuality was illegal under the regime.

The result, a compassionate insight into their lives as they apply their makeup, pose in slip and suspenders, try on earrings or recline seductively on a bed. Their eyes speak of defiance and pride, but also reflect the constant terror that they might be arrested and tortured. As they were.

One gruelling account by a transvestite called Pilar talks about being seized, put on a boat off the port of Valparaíso, beaten, urinated over and hung from ropes. “They killed one,” Pilar recalls. “She looked like Liz Taylor.”

Errázuriz was travelling along the border with Peru when she came across La Casa de las Muñecas (the House of Dolls), a brothel. Again, she spent many months getting to know the workers and, unusually for her, used colour film instead of her habitual black and white which effectively contrasts the undoubtedly seedy quarters of the dolls, with their own matter-of-fact, half-clothed, lack of inhibition.

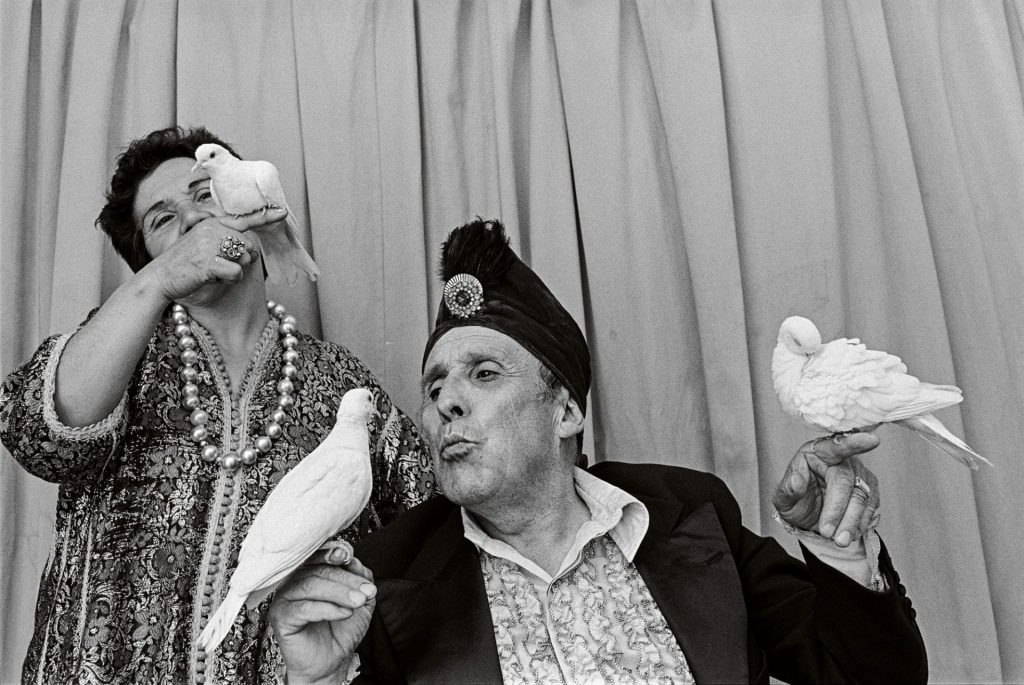

If they are bold, she represents the young men in Boxers, the Fight against the Angels (1987), not as virile fighters, sporting trophies, but rather vulnerable, not sure what to do with themselves outside the ring. She brings a lightness to El Circo (Circus), which took her five years living for long periods with an itinerant circus; we meet a dwarf in a Miss Piggy mask, a magician about to do a trick with ping pong balls (with one in his mouth), another with doves.

She does photograph protesters brave enough to march on the streets, defying the police, daubing graffiti, but the most subversive portrait is one of a boy perched on a bed wearing a grotesque hood of Pinochet. Mickey Mouse posters on the wall add a sly mockery.

Suggested Reading

Zed Nelson’s unnatural world

The malign influence of the regime means despair is all pervading. She heard that many of the “disappeared” ended up in psychiatric hospitals and she went looking for lost friends but instead discovered that in the grim and uncaring confines of the hospital several patients had found love. They were banned from marriage, many were known only as NN No Name, but in Seclusion. Heart Attack of the Soul (1994) the tenderness of their feelings for each other is palpable.

The scenes from Antechamber of a Nude (1999) “terrified her” when she first visited. “It was like a concentration camp.” She found it “deeply touching” that people who had never thought that their bodies could be of interest were prepared to let her photograph them in communal shower blocks, grimy surroundings of concrete walls and wire grills. Undignified is the least of it. Bodies are portrayed with unflinching honesty yet somehow, maybe because it is Errázuriz taking their pictures and they trust her, there is a glimmer in their eyes of self-belief.

“Everybody can make what they want out of these pictures,” says Errázuriz. “It is the viewers’ eyes that make them, not me.’ But it is more than that. In portrait after portrait, she offers the lost a chance to be found by bringing them in from the outside. Now, rather, it’s their turn to stare at the viewers, and more, to dare to look beyond their margins.

Paz Errázuriz: Dare to Look; Hidden Realities of Chile is at MK Gallery until October 5.