A question mark hangs over the G20 gathering of the world’s largest economies as it convenes in Johannesburg for the first time ever on African soil: Do international summits still matter in the age of Donald Trump?

The US president isn’t in South Africa, nor is he sending a stand-in. In his second term, Trump is conspicuously reinforcing the diplomatic predilections of his first. He eschews hours-long deliberations at multilateral forums in favour of bilateral meetings or micro-drama-style televised sit-downs in the Oval Office.

Even so, the international summit is a staple for numerous thrillers, has long been the frame for writerly visions of world peace and remains an institutionalised part of the world order.

Exactly 75 years after Winston Churchill suggested “summit” as a term for international diplomacy at the very highest level, it symbolises the aspirational peak of high-stakes problem-solving.

Cambridge academic David Reynolds explains as much in Summits: Six Meetings That Shaped the Twentieth Century. He lays out how Churchill arrived at the term in the dark days of the cold war.

In 1950, Churchill called for high-level talks with the Soviet Union saying it was “not easy to see how matters could be worsened by a parley at the summit”. The reason for this talk of summits was ongoing attempts to scale Everest, the world’s highest peak. Churchill continued to speak of the need for a “summit of nations” over the next few months and years and in May 1953, he did so again in the British parliament. By month’s end, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had become the first known human beings to stand on the highest point on Earth.

Reynolds writes, “the Everest obsession helps explain why Churchill’s metaphor rooted itself in popular consciousness”. By 1955, “summit was picked up as an official term by the US State Department. Cartoonists portrayed world leaders eyeing a peak or perched uncomfortably on its top”. Suddenly, the summit had become the pinnacle of international leadership and negotiation.

That said, summitry is as old as diplomacy itself. Reynolds points to examples dating back to Bronze Age Babylon, fourth-century BC Greece, the Byzantine Empire and most famously, between England’s Henry VIII and France’s Francois I on the so-called Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520.

His specific focus, though, is six significant summits of the last century: Munich (1938), Yalta (1945), Vienna (1961), Moscow (1972), Camp David (1978) and Geneva (1985). All showed the possibilities – and perils – of personal engagement by national leaders when they came to solving problems by negotiation.

But perhaps the most consequential and least-studied summit of the past 100 years was the Bretton Woods gathering of 1944. Ed Conway’s starkly titled The Summit tells the history of the turbulent transformational conference that continues to undergird the global financial system today.

At a crucial moment, during world war two, the Allied nations sent economists to the Bretton Woods summit in New Hampshire, hardly daring to hope for success. It led to the establishment of the International Monetary Fund and what became the World Bank Group. It was the only time countries from around the world have agreed to overhaul the structure of the international monetary system.

Meanwhile, novelists have had their way with summits, as an aspirational tool as well as a malleable plot line. An early example is The World Set Free. One of HG Wells’ lesser-known novels, it deals with a summit called by a fictional French ambassador based in Washington in response to the threat posed by mankind’s power to wreak devastation by “atomic bombs”.

Wells’ prediction of nuclear warfare, decades before Robert Oppenheimer’s development of the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, highlights the power of international summitry. He caustically writes: “Men who think in lifetimes are of no use to statesmanship.”

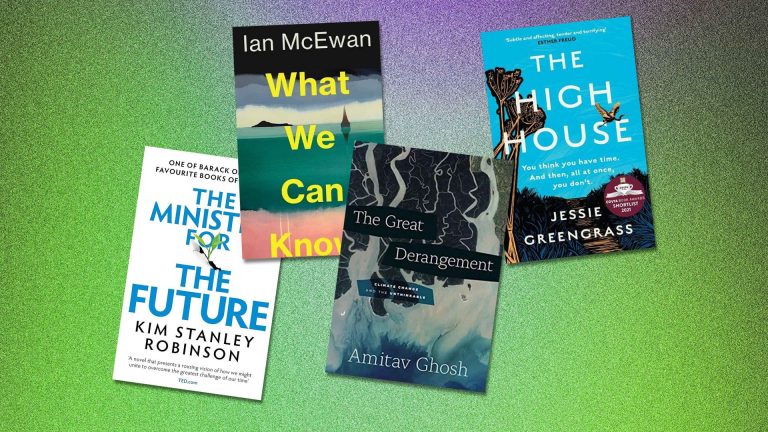

Suggested Reading

When climate fiction stops being fiction

The fictional summit leads to an agreement to form a one-world government that will try to end all wars. Ironically, the book was published the year the first world war started.

Even so, reassuringly for this format of international diplomacy, many modern thrillers continue to repose faith in the summit, if only for its dramatic possibilities.

Terry Fallis’s Operation Angus and Mark Terry’s The Fallen revolve around summits – not the G20 but the G8. Fallis, who is Canadian, features Angus McClintock, an accidental politician who has become a bestselling character in a series of comic satirical novels. McClintock is travelling around Europe, ahead of the summit in Washington DC, when he receives a warning from a British secret agent that Chechen separatists are planning to assassinate the Russian president while he visits Canada. The rest, as they say, is the novel.

Coincidentally, Mark Terry’s potboiler is also set around a G8 summit. This one is in Colorado Springs in the US. A terrorist group manages to infiltrate the summit and take many world leaders hostage. Only one man has any agency at this point.

It all does work out, which is more that can always be said of actual summits.

Rashmee Roshan Lall’s Substack blog This Week Those Books explains current affairs by recommending books by experts