There’s a buzz around women’s sport right now, as the rugby world cup ends with a sold-out final at Twickenham and its cricket counterpart begins in India and Sri Lanka. There, tickets have been priced at record lows – less than a pound apiece – in the hope of packing out stadiums.

After the hugely successful women’s Euros, the continued growth of England’s football Super League and the US Women’s NBA, plus a new generation of superstar female athletes that takes in rugby’s Ilona Maher and basketball’s Caitlin Clark, the much-discussed tipping point for women’s sport may have finally arrived. Total global revenues are expected to rise to nearly £1.8bn this year, a huge leap from £508m in 2022.

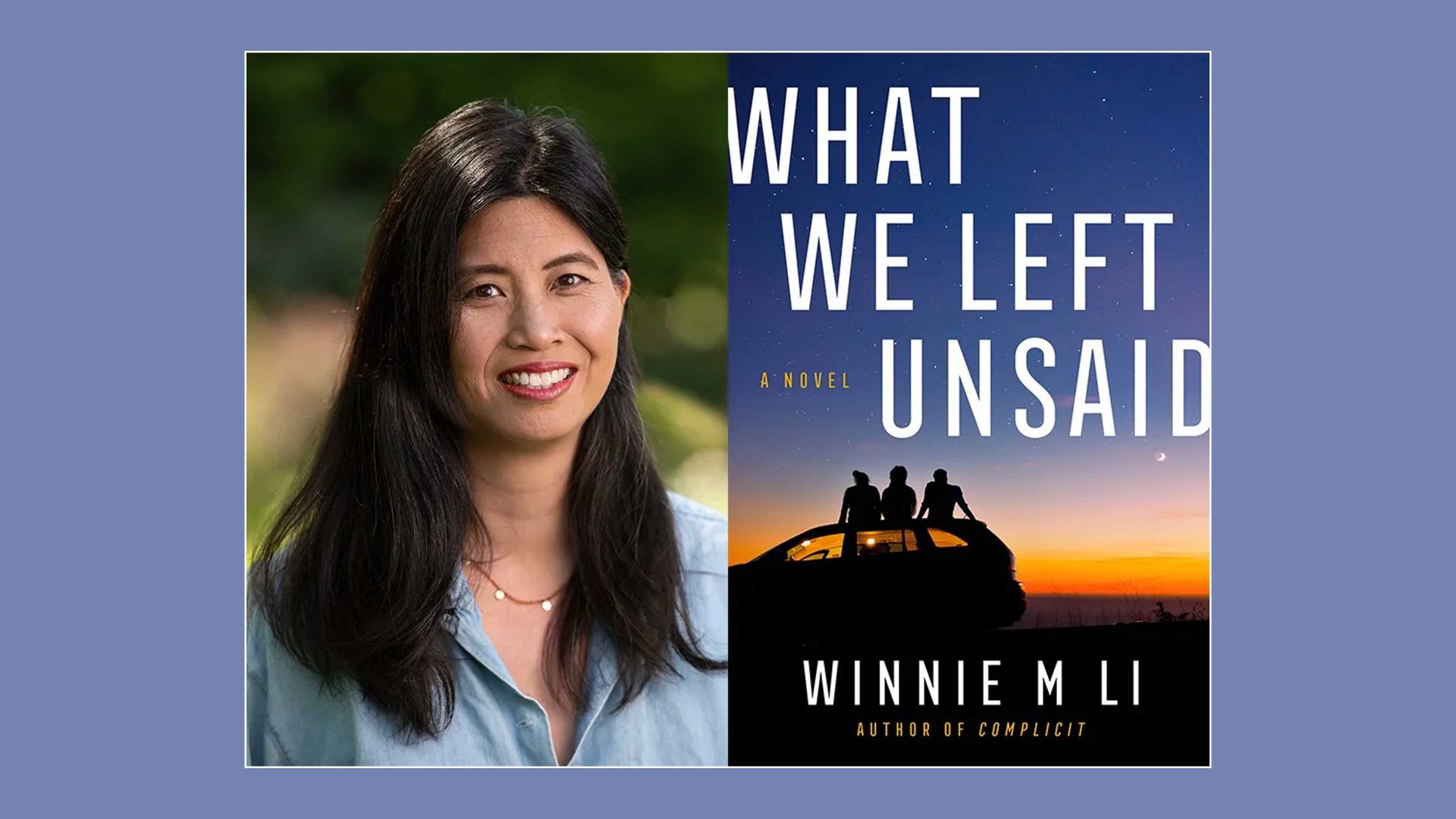

Yet it all sounds almost unbelievable when set alongside three books about women’s sport, all published within the last five years. Each author brings a different perspective – practitioner; historian; journalist. Each book notes progressive advances over time; all lament the slow process of change.

The point about Girls Don’t Play Sport by Australian rugby union player and Olympic gold medallist Chloe Dalton is in its title. The crossing out of the word “don’t” on the book’s cover is both an assertion and an admission. Dalton offers herself up as proof that girls do play sport and to high standards.

She lays out the many reasons women’s sport is “entire generations behind the men’s game”. These include underrepresentation, “from playing to coaching to administration and management”. And linguistic devaluation. “I am known as a female athlete who plays women’s sport. Have you ever heard Tiger Woods referred to as a male athlete who plays men’s golf?”

She notes that men’s sport has always been “the default” and when a women’s competition is introduced, a ‘W’ is simply added to the default name without recognising that “for female athletes, language can be a harmful tool that reminds them that they are not part of the fabric of sport – that their contribution is added in, second string”.

Suggested Reading

Has Prada walked Indian footwear into the mainstream?

Dalton is also good at recording key moments in the struggle for recognition, a hidden history that must be celebrated. Women competing in the 1900 Olympic Games for the first time in history. Frenchwoman Alice Milliat founding the International Women’s Sport Federation in 1921 and creating “women’s only” events that drew spectators, global attention and eventually that of the sports authorities too.

And Kathrine Switzer, the first woman to run the Boston Marathon in its 70 years of existence. Dalton writes that when Switzer completed it in four hours and 20 minutes in 1967, she crossed “the finish line for women across the globe”.

Sports historian Marion Stell examines slightly different parameters of achievement in The Bodyline Fix: How Women Saved Cricket. The book offers fascinating detail on the inaugural Australia v England women’s Test series. Now called the first women’s Ashes, its 90th anniversary was marked with a historic test at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in January 2025, won by Australia.

Stell explores the role played by Australia’s women cricketers in restoring the sport’s reputation after the infamous men’s Bodyline series of 1932-33. Using interviews, scrapbooks, diaries and other archival material, she tells a story of passion and pragmatism.

Women taking up cricket back then did so without encouragement, without equipment, without mentors. Still, Don Bradman’s mother, Emily, was an accurate bowler who “regularly bowled her left-armers to him each afternoon after school”, but few knew of her role in raising a boy who went on to be arguably the greatest batsman of all time.

One female cricketer of the time wryly notes the perils of her own childhood practice sessions: “Playing in the streets required accuracy and restraint, especially during the Depression: ‘If we hit the ball into a particular lady’s place she’d keep the ball…”

Guardian journalist Suzanne Wrack’s book, Woman’s Game: The Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of Women’s Football, examines other limiting factors: Male condescension, outright misogyny and a 50-year ban in Britain.

When Londoner Nettie Honeyball (aka Mary Hutson) launched the pioneering but short-lived British Ladies’ Football Club in 1895, she wanted to prove that “women are not the ‘ornamental and useless’ creatures men have pictured”. Through the suffrage movement, football became a form of feminism.

During the first world war, with men’s leagues suspended, roughly 150 local women’s football teams were established and became enormously popular. Astonishingly, the high profile of the women’s game earned it a half-century ban by the Football Association, which declared the sport “unsuitable for females”. The ban was lifted only in 1971.

Wrack is clear in the “manifesto” at the end of her book, that the women’s game should not be “a mirror of the men’s” but a more wholesome force for social change.

It’s a worthy goal and endorsed by many. Thus far, it lacks a roadmap.

Rashmee Roshan Lall’s Substack blog This Week Those Books explains current affairs by recommending books by experts