On August 14 and 15, India and Pakistan will mark 78 years as independent nations. These may not be milestone birthdays, but they will feel significant nonetheless in light of heightened tension between the South Asian neighbours. Barely 12 weeks ago, they were engaged in what defence experts describe as a “near-war”. For the first time in half a century, India and Pakistan struck deep into each other’s territory, sending drones and missiles across their heavily fortified border to reach teeming cities on either side.

Those four days of deadly hostilities have frightening implications for two nuclear-armed states with a fractious history and little apparent will to overcome it. After the flare-up, a dispiriting consensus emerged: the India-Pakistan relationship is so fraught that there will almost certainly be other crises, of escalating severity and with growing risks of catastrophic miscalculation. Screaming headlines around the world suggested the conflict is testing the threshold for nuclear war.

How did the subcontinental siblings get to this point? Born in mid-August 1947 a few hours apart, India and Pakistan had much to share. Culinary tastes and cultural affinity, not least a passion for cricket. Language. Family ties. Rivers. Crucially, they had the same backstory of a struggle for independence from Britain.

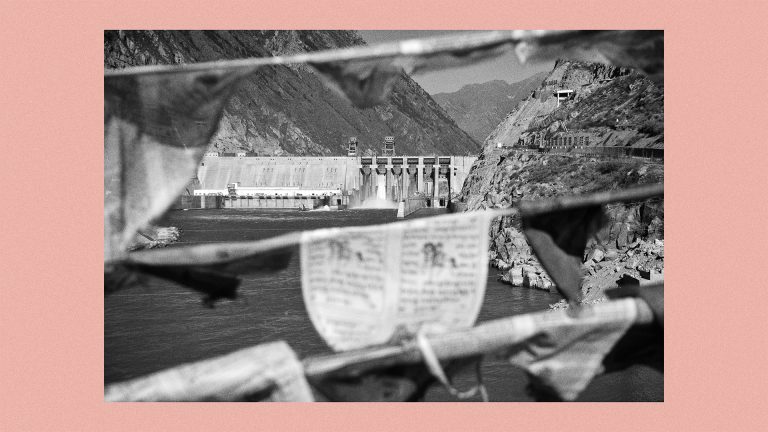

But in the past few decades, the neighbours have metaphorically moved further apart, suspending already scant transport links and people-to-people exchanges. There are no direct trains or flights, trade relations have been frozen for years and the latest near-war led India to put in abeyance a 65-year-old water treaty that allowed the two countries to share the Indus River.

The story of India and Pakistan today is best understood through four books published within the past 20 years. Their Indian and Pakistani authors journeyed to the other side for business or pleasure and emerged with a nuanced view of the enmity that seems so entrenched. In various ways, each account brings into focus a grim reality that the subcontinent still lives with the trauma of its moment of rupture, when a bloody partition gave rise to separate countries.

The point about Coming Back, Shueyb Gandapur’s 2025 account of his travels in India, is the audacious title. A Pakistani who put himself through the grinding bureaucratic process of acquiring a visa to visit India, Gandapur tells it like it is. He is “coming back” to a place he has never been but feels he knows in his bones.

Before partition, members of his family had left their dusty town in north-western Pakistan to make their fortune in an area that lies in present-day India. The great displacement caused by partition forced them back. They, like most other Pakistanis, spoke of India “in mixed tones of warmth and rancour,” Gandapur told the New World. He was riveted by his grandfather’s stories about life in India and transfixed by the Bollywood films he could easily understand, because Hindi sounds so much like Urdu. Curious about “the common ethos of Hindustani culture” that transcends the border as well as religious differences, it became Gandapur’s “dream” to visit India.

It wasn’t easy. “Despite sharing the same subcontinent, my turn to visit India came after I had visited twice as many countries as my age,” he writes. Granted no more than a four-city visa – Delhi, Agra, Jaipur, Varanasi – and required to check in with police in each, he writes of the hostility and hospitality he receives and the tenuous invisible ties that still link Indians and Pakistanis despite years of acrimony.

Suggested Reading

The next India-China war

But in some ways, Gandapur’s account too is of a vanished world. He travelled to India in 2017. In the years since, two near-wars have rendered India and Pakistan even less accessible to each other.

It is the doleful sense of increasingly becoming “distant neighbours” that preoccupies former Indian diplomat Rajiv Dogra. He was India’s last consul general in the Pakistani port city of Karachi before the host country ordered the mission to close in 1994.

Drawing on Dogra’s professional experience of Pakistan as well as anecdotal material, Where Borders Bleed goes back over old ground – the unfinished business of partition – but in a new way. He tries an alt history, speculative and dreamy in its counterfactual basis. What would it mean if “PakIndia” were a single entity? Could India and Pakistan go the way of Germany and become one again?

But then he recounts a story told by a Karachi friend of a long in-flight conversation with Pakistan’s foreign minister. Asked what he wanted to achieve while in office, “the minister stretched both his hands in front of him, opened his palms facing skywards and said, ‘If God were to grant me a wish, I would ask him to place a nuclear bomb on each of my palms.’ Then, with a satisfied smile, he turned his palms downwards and added, ‘One I would drop on Bombay, the other on Delhi’.”

Prominent Indians may have their own equally startling wishlists and academic Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar explains some of the fervour by focusing on the “long partition” still endured by both countries. Of Pakistani heritage and from a family divided across borders, Zamindar spent more than two years on ethnographic and archival research to suture the “severed histories” of 20 million forcibly displaced people. The result is The Long Partition, a highly readable book, which emphasises the “bureaucratic violence” that added to the collective suffering.

Both India and Pakistan weaponised religion from the beginning, she says, with refugee status turned into “a governmental category… marked by religious community”. Thus, post-colonial India was “able to push out and dispossess Muslims… as it bounded a new nation for the well-being of ‘our people’.”

And Pakistan, which claimed ideologically to “safeguard” the interest of all Muslims on the subcontinent, argued “it could simply not accommodate all the Muslim refugees that might want to come to Pakistan from India”. The decades since have only ossified the divide, resulting in a continuing and long partition.

But sometimes, there are desperate attempts to bridge the gap. Urvashi Butalia’s The Persistence of Memory tells one such story. Bir Bahadur, an elderly Sikh man in Delhi, briefly makes it back to his ancestral village in Pakistan more than half a century since his family abruptly left. His goal is to ask forgiveness because Bahadur’s family – the only Sikhs in a village of Muslims – had distrusted their promise of security as independence neared and communal tensions sharpened.

The reunion, watched by Butalia and a Japanese radio journalist, is bright with laughter and unshed tears. For a brief moment, the simple, brutal political geography of partition is transcended.

Rashmee Roshan Lall’s Substack blog This Week Those Books explains current affairs by recommending books by experts