Last month, Tommy Robinson arrived in Israel. The former leader of the English Defence League and long-time agitator against Islam documented the trip in a stream of social media videos and posts, filmed across Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and several towns in the south of the country. He met with right wing activists and a handful of political figures, visited communities near the Gaza border, and repeatedly declared Israel “the world’s front line against terror.”

Robinson described the country as a model of national strength and moral clarity, “a nation that still knows who it is.” He contrasted it with what he called “Britain’s decline under multiculturalism.”

For his supporters, the trip was presented as a moment of moral reckoning. The imagery of Robinson standing before an Israeli flag, touring the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial centre, addressing followers from “the Holy Land,” and invoking biblical language was carefully constructed to suggest transformation: that the man long condemned for bigotry had become an ally of the Jews.

His visit came in the wake of the Manchester synagogue killings, and while controversy raged over a ban on Maccabi Tel Aviv fans at Aston Villa, at a moment when antisemitic attacks in Britain and across Europe have surged to levels unseen in decades. Against that backdrop, gestures of solidarity can appear seductive, even when their source should provoke unease.

Yet beneath the performance of friendship lay a familiar pattern. Robinson’s rhetoric throughout the trip, praising Jewish strength while condemning “liberal elites,” revealed not repentance but repositioning. His pilgrimage was a calculated act of rebranding, an attempt to recast an anti-Muslim demagogue as a defender of Jewish civilisation.

This shift did not occur overnight. For several years, Robinson has been cultivating a narrative that blends admiration for Israel with resentment toward Jews who do not share his politics.

His praise for Israel comes hand-in-hand with attacks on “liberal Jews” and Jewish institutions in Britain. The journey to Israel was not an end but a culmination of a long ideological evolution that began, in writing, with a document whose title exposed its essence: his 2022 essay The Jewish Question.

Published on, and later deleted from, his Urban Scoop website, this remains Robinson’s most explicit statement about Jews and Jewish power. The title itself evokes a phrase with a grim lineage.

In 19th-century Europe, “the Jewish Question” referred to the debate over whether Jews could ever belong as equal citizens. In Nazi Germany, it became the justification for extermination. To resurrect the term in 2022 was not an act of inquiry but an act of continuity.

The essay begins by defending Kanye West’s claim that Jews control the media. “Ye was telling truths others fear to say,” Robinson writes, arguing that the backlash against West only proved his point. In one passage, he insists that “every major media network and record label is run by the same small group” and that “to question it is to be destroyed.”

This reframes the old conspiracy of Jewish control through the vocabulary of digital grievance: censorship, cancel culture, and victimhood. The logic is circular. Antisemitic speech supposedly proves Jewish power because it provokes condemnation, and condemnation supposedly proves the conspiracy because it silences dissent.

Suggested Reading

Tommy Robinson’s march was a drunken, coked-up mess

Robinson claims that “liberal Jewish elites dominate culture and redefine racism to target white people.” His citations are a patchwork of biographies, Wikipedia entries, and screenshots. It is the classic method of conspiracism: mistaking visibility for proof of control.

Though Robinson repeatedly insists that he does not “blame all Jews,” his qualification collapses under the weight of his argument. He accuses “liberal” and “left-wing Jews” of betraying traditional values and creating “a hostile environment for ordinary Jews.” He praises “strong conservative Jews” for defending Israel and condemns others as “weak and self-hating.”

The division is moral and political rather than theological, yet it echoes the old pattern of separating the “good Jew” who assimilates from the “bad Jew” who corrupts. The supposed respect masks a hierarchy that rewards submission and punishes dissent.

This document laid the foundation for Robinson’s later self-presentation. His claim to love Israel was never about Jews themselves, but about what they could symbolise: strength, identity, and defiance. His visit to Israel in 2025 did not contradict his essay; it completed it.

Three years after the publication of The Jewish Question, and just two weeks before his trip to Israel, Robinson posted a video following the Manchester synagogue attack. What might have been an occasion for sympathy quickly revealed the continuity between his earlier essay and his 2025 persona.

“Let me explain to you what’s going on here,” he began, responding directly to the attack. “The elitist Jews, the woke liberal Jews, the ones like the Board of Deputies who are pro open borders, they don’t represent all Jews. Netanyahu and his government are conservatives. They’re not woke, they’re not liberal. The liberal Jews have created the hostile environment for ordinary Jews.”

He went on to accuse “liberal elites” of “spending years cuddling up to Islam and mass immigration,” and claimed that Jewish communal leaders had “created the very problem they now face.” He contrasted these figures with “real Zionist Jews” who “stand strong, not weak,” describing Israel’s right-wing government as the authentic voice of world Jewry and dismissing liberal Jews as “traitors to their own people.”

In a few minutes, Robinson distilled the core argument of The Jewish Question: that antisemitism is not the fault of antisemites but of Jews themselves, or at least of the wrong kind of Jews. By dividing the Jewish community along ideological lines, he presented himself as a better defender of Jews than their own institutions.

The ideological function of this division is clear. It recasts antisemitism as a problem Jews should solve by altering their politics. The logic is ancient: that Jews bring hostility upon themselves through disloyalty or cosmopolitanism, and that redemption lies in conformity to the dominant culture.

Suggested Reading

Tommy Robinson’s long shadow

Robinson’s version modernises this idea for the age of culture wars. His “ordinary Jews” are those who share his worldview; the rest are complicit in their own victimisation.

This inversion of victimhood serves a dual purpose. It absolves the bigot while indicting the victim, converting hatred into a lesson about strength. It also reinforces Robinson’s self-image as a truth-teller besieged by elites. By redefining antisemitism as a form of moral correction, he cloaks prejudice in the language of protection.

And in doing so, he twisted a moment of mourning into propaganda. At the very time Jewish communities were grieving victims of antisemitic violence, Robinson turned that grief into proof of his own righteousness.

During his 2025 visit, Robinson repeatedly praised Israel as “the front line of the West” and “a nation that still knows who it is.” These phrases, shared across his videos and interviews, strip Jewish self-determination of its complexity. The Israel he celebrates is populated not by real Israelis but by archetypes: the soldier, the settler, the survivor. His rhetoric flatters, yet beneath the admiration lies a rebuke to Britain, a lament for what he sees as his country’s decline into self-doubt.

This is not a new phenomenon. Throughout modern European history, the right has often expressed admiration for Jews when they seemed to confirm right-wing ideals. In the 19th century, conservatives romanticised Jewish unity as a model for national revival. In the 1930s, fascists praised Zionism as proof that races should live apart. After 1948, segments of the Cold-War right embraced Israel as a bulwark against communism; after 9/11, as the vanguard of a global struggle with Islam. In every case, Jews were admired not as people but as instruments of another ideology’s self-definition.

Robinson’s invocation of Israel continues this pattern. His “support” transforms Jewish history into validation for English nationalism. When he praises Israeli resilience, he is really mourning British weakness. When he speaks of “a people who never apologise,” he is lamenting what he sees as his own nation’s moral exhaustion.

Jewish experience becomes a parable for the restoration of Western confidence, a story about Britain told in borrowed symbols. His philo-Semitism is therefore a form of projection: he loves in Jews what he believes his own culture has lost.

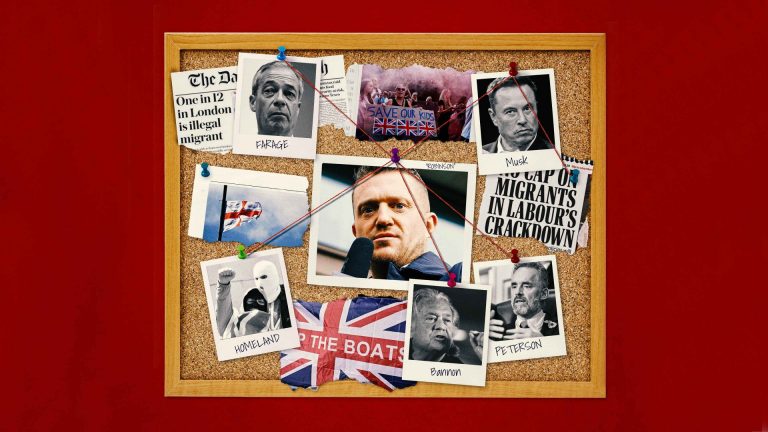

Robinson’s sudden affinity for Israel does not exist in isolation but as part of a wider ideological current reshaping the European right. Across Europe and North America, the populist right has discovered the political utility of professing love for Jews.

The far right that once trafficked in open antisemitism now recasts itself as the Jews’ protector. Figures such as Marine Le Pen, Viktor Orbán, and Giorgia Meloni speak admiringly of Israel’s nationalism and military strength, presenting the Jewish state as a model for their own societies.

In the United States, Donald Trump and his allies praise Jewish success and champion Jerusalem while recycling insinuations about loyalty and control that would once have been condemned as antisemitic. These gestures of admiration have in some cases encouraged better diplomatic and communal relations, but they also carry familiar undertones: public praise serving as moral camouflage.

Robinson’s rhetoric follows this pattern. His talk of “shared values” and “defending the West” replaces religious hatred with the language of cultural struggle. Where he once warned that Muslims were “taking over Britain,” he now points to Israel as proof that strong nations can resist cultural invasion.

To many observers, that might seem like progress: a man once consumed by hatred now expressing admiration. Yet the structure of thought remains unchanged. The Jew is still a mirror in which Europe defines itself, still a vessel for its anxieties about decline and identity.

Robinson called his visit to Yad Vashem “a very moving experience,” saying it helped him understand “why this homeland, why this place of safety is so important,” and urging that “we must stand together against those who seek to destroy it.” Such sentiments deserve acknowledgment; remembrance can awaken conscience.

Yet his words carried the same undercurrent as the rest of his trip: turning Jewish tragedy into a parable of strength, using the Holocaust to reaffirm his own narrative of cultural survival. True reckoning with antisemitism requires more than sympathy for its victims; it demands abandoning the conspiracies and divisions that sustain it. Holocaust memory must not be allowed to serve as moral theatre.

Tommy Robinson’s journey from street agitator to self-styled ally of Israel has been presented as a story of transformation. In truth, it is a story of adaptation. His philo-Semitism is not the negation of his earlier hatred but its mutation into a form that suits the times. It asks Jews to serve as proof: of the West’s strength, of Britain’s decline, of the righteousness of one tribe over another.

Taking antisemitism seriously means rejecting not only those who hate Jews outright, but also those who would use that hatred for their own redemption. The only adequate response is to refuse the premise. The Jewish story is not an accessory to Britain’s culture wars, nor a test of anyone’s political virtue. It is its own story, and it needs no interpreter – least of all, Tommy Robinson.

Raoul Wootliff is a strategic communications consultant focussing on international reputation building. Hailing from the UK and currently based in Israel, he was formerly the Times of Israel’s political correspondent and producer of the TOI Daily Briefing podcast. This article draws on themes from The Jewish Question Revisited: Tommy Robinson, Corbynist Populism, and the Ideological Grammar of Modern Antisemitism, first published in Fathom Journal.