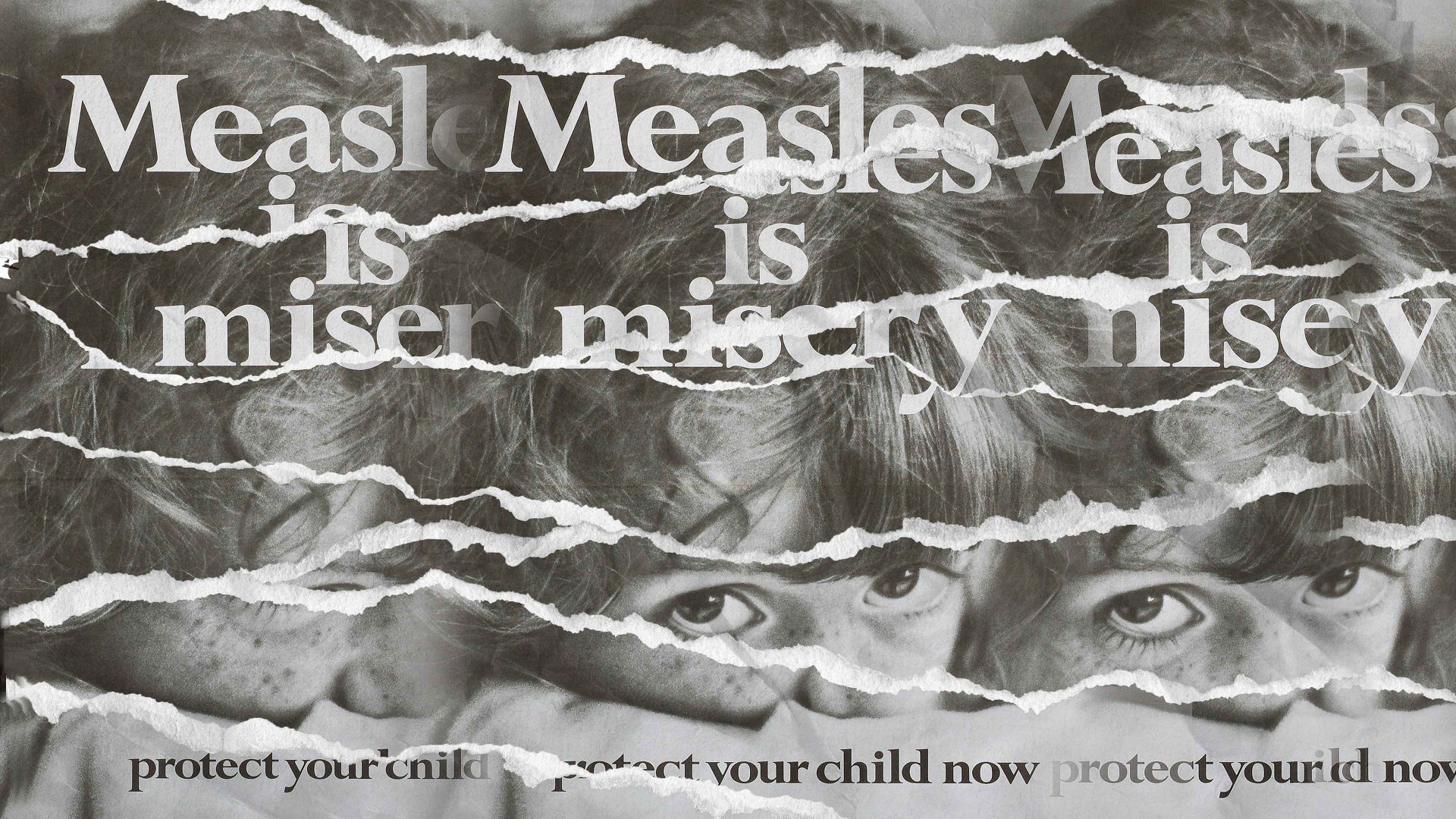

The death of a child from measles at the Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool in July has forced a reckoning with the unpalatable truth that this infectious disease has returned as a serious hazard to public health. And while the precise circumstances of the child’s death are not known, the reason for the growing crisis is clear enough: not enough parents and carers are giving their children the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) jab.

In Liverpool the rate of uptake for both doses of the vaccine is just 74%, lower than the national average of around 83% and considerably below the target of 95% cited by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the necessary coverage for herd immunity in the population.

What is causing this vaccine hesitancy? Many healthcare experts may be thinking: didn’t we already win this argument? The claim made in 1998 by Andrew Wakefield, a doctor at the Royal Free Hospital in London, that the MMR jab was linked to cases of autism, has been thoroughly debunked. In 2010 the General Medical Council found Wakefield guilty of misconduct in his research by falsifying results, and struck him off their register. While some pressure groups continue to recycle the discredited claim, studies have convincingly shown that there are no known long-term adverse impacts of the vaccine and that it confers effective protection against these diseases.

Yet uptake of the MMR vaccine in the UK has fallen to its lowest level in a decade, and as a consequence measles is having a resurgence. In 2023 there were outbreaks in the West Midlands and Birmingham, with most cases seen in children under 10. The Liverpool death has thrown a spotlight on the uptick in measles cases in the Merseyside and Wirral areas over the summer. In 2008 measles was declared endemic – circulating at a sustained low level in the population – in the UK for the first time in 14 years, and in May of that year a 17-year-old with underlying congenital immunodeficiency died of acute measles infection.

This problem is not specific to the UK. The WHO and Unicef warned earlier this year that measles cases across Europe are higher than they have been for a quarter of a century. “Measles is back”, said Hans Henri Kluge, WHO’s regional director for Europe. In the US, the chaos and anti-vaccine sentiment in the new health administration has led to a surge, with outbreaks in Texas and New Mexico in which one (unvaccinated) child has died. As of early July, more than 1,200 US cases have been reported for 2025, nearly all of them in those who are unvaccinated or whose vaccination status is unknown. There have also been outbreaks in Madagascar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Liverpool case was a reminder that measles, which many parents think of as a mild and transient nuisance, can be serious and even fatal. It is caused by a virus (Morbillivirus), and usually produces cold-like symptoms and an itchy, inflamed rash but can also lead to ear infections, pneumonia (the most common cause of measles-related deaths in children), and, in rare cases, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and respiratory problems. Women who get it during pregnancy are particularly at risk, as it can cause premature birth, miscarriage and stillbirths. While the vast majority of cases come and go, it’s still pretty horrid – you don’t want to get it. But it’s terribly easy to do so if you’re not vaccinated, because the disease is highly contagious.

A double dose of the MMR vaccine is 99% effective at giving lifetime protection from these three diseases. It is offered as a routine and free part of the NHS’s Childhood Program, with one of the products on offer being free of pig-derived gelatin for those whose religious beliefs or customs demand that.

Despite this easy and readily available solution, “uptake is nowhere near what we need to achieve,” says Vanessa Saliba, an epidemiologist at the UK Health Security Agency and a specialist on planning and implementation of immunization programmes. It’s not a new problem: coverage of the MMR vaccine has been declining for over a decade. The Covid pandemic exacerbated this trend, but only slightly: uptake dipped from 2020 to 2022, probably due mostly to the difficulties of simply getting to surgeries for the jab.

The national trend hides a lot of variation though. “We know that there are inequalities in uptake by geography, by ethnicity, and by deprivation,” says Saliba. In general, she says, “the areas that are most diverse, urban, and have highest deprivation, have the lowest uptake.” The communities at highest risk of outbreaks are migrant populations, traveller communities, and ultra-orthodox Jewish communities.

Suggested Reading

Trump’s war on scientific truth

This alone indicates that the problem is complex, and that the caricature of middle-class mums consuming and spreading vaccine misinformation on Mumsnet simply doesn’t apply. No single factor accounts for low vaccination rates in all those different groups. Some won’t get vaccinated because they are itinerant; others might be mistrustful of authority; others might have conflicting belief systems. Some simply don’t have good access to information about what is available, or the resources to get their children to a GP.

But while the factors driving the relatively low vaccine uptake are complicated, vaccine hesitancy – a reluctance, ambivalence, or refusal to get the jab – clearly plays a role. Vaccine hesitancy has been recognised by the WHO for more than two decades, and the organisation identified it in 2019 as one of the top ten threats to global health. A WHO working group on the issue has acknowledged that this problem is context-specific, varies over time and place, and is vaccine-specific. It is not in itself a recent phenomenon, but many health experts agree that it has escalated in scope and scale in the 21st century.

Heidi Larson and Christopher Murray, two experts on the subject at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, say that a decline in trust in expertise, political polarization, and the hyperconnectivity of the internet and social media have all played a part. One doesn’t need to believe that vaccines contain microchips or poisons to become hesitant; all it takes is a seed of doubt, especially when it comes to parents making choices for their children.

That was what Wakefield sowed with his 1998 paper in The Lancet (retracted only in 2010) on the spurious correlation between the MMR vaccine and autism. The paper caused a sharp decline in MMR compliance, from 92% in 1996 to 84% in 2002. A major review by the US Institute of Medicine, published in 2004, showed no evidence of any link to autism. But, once Wakefield’s message was abetted by credulous media coverage and celebrity endorsement, the damage was done. Wakefield subsequently became an anti-vaccine activist, directing a 2016 anti-vax film Vaxxed: Form Cover-Up to Catastrophe. The most notorious advocate of Wakefield’s claim is the US health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr, a long-time vaccine sceptic who is convinced that autism has some “environmental” cause and has long pushed quack cures such as cod-liver oil for all manner of diseases.

While such antivax messaging initially spread through traditional print and broadcast media, it was one of the earliest examples of “fake news” and conspiratorial misinformation to be boosted by social media. “The role of social media in fuelling the spread of vaccine hesitancy and its increasingly documented health consequences cannot be overstated,” say Larson and Murray.

Unsurprisingly, they observe that vaccine hesitancy reached new levels during the Covid-19 pandemic, when distrust of the new Covid vaccines merged seamlessly with the existing narrative created by the MMR controversy. The pandemic hypercharged the information ecosystem through which vaccine distrust and misinformation spreads, connecting far-right and hate groups intent on fostering conspiracy theories with groups previously focused on “alternative” healthcare and well-being. In the US these networks are now part of the mainstream, aided by the conspiracy-fixated Trump administration. Inevitably some of the toxic fallout blows across the Atlantic.

There is no avoiding the fact that ethnicity is a strong factor in vaccine hesitancy. A 2021 report from NHS England says that it is highest for Black people, followed by the Bangladeshi and Pakistani communities. The document suggests this might be driven in part by “by a lack of trust in the medical profession due to historical discrimination, racist ideology and immoral experimentation on people of colour” – in other words, by entirely understandable worries. Covid added to the problem here too. In April 2020 a French clinician suggested that Africa was an ideal testing ground for future anti-Covid vaccines because “there are no masks, no treatment, no intensive care” – an idea later echoed by others, but which the WHO rapidly condemned. It’s little surprise, then, that around 72% of Black people surveyed in the UK said they would be unlikely to take part in a study at that time of Covid vaccines, whereas 84% of white British people said they would.

There is surely no easy or one-size-fits all solution to this problem. It’s certainly not a matter of simply asserting more loudly that vaccines are safe and protect people’s health (however true that might be). People concerned about vaccines need to feel heard, not admonished. “Healthcare providers need to offer support and encouragement and listen to what matters from the patient’s perspective”, say Larson and Murray. As experience with the Covid vaccines showed, communities particularly hesitant about vaccines need to hear the messaging from people they trust, not just from NHS websites or the government. “The messenger can be more important than the message,” says Larson. “The advice of trusted primary healthcare providers, families and friends is often much more influential than the cold facts of official sources.”

The return of measles is a reminder that public health is and always has been as much a matter of politics and sociology as it is of science. “The story of measles is one of remarkable progress,” say epidemiologists Amy Winter and Spencer Fox of the University of Georgia. “What was once a leading cause of childhood death has become a vaccine-preventable disease, with elimination achieved in many countries. Yet the recent resurgence in the Americas underscores how fragile elimination can be when vigilance wanes.”

Because it is one of the most contagious of vaccine-preventable diseases, they add, “measles is the first to re-emerge when vaccination systems falter”. But “it is unlikely to be the last”.