“Nothing is too good for ordinary people,” declared Russian-born British architect Berthold Lubetkin in 1938. He was speaking at the opening of the Finsbury Health Centre, a pioneering facility he’d designed to provide medical services to deeply deprived communities in central London. It is hard now to imagine how futuristic the building must have seemed at a time when many Londoners didn’t even have indoor toilets. The spaceship-like facility featured a convex glowing entrance of glass bricks flanked by two gleaming wings of treatment rooms, flung wide like arms offering a hug.

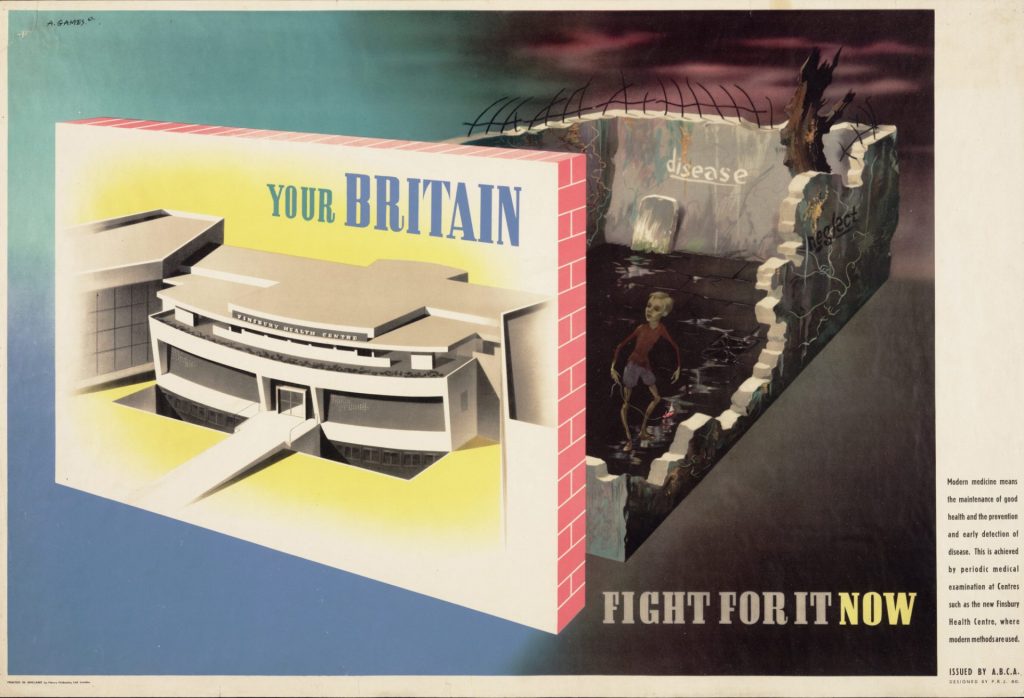

Lubetkin said the welcoming design was intended to “introduce a smile” – an overtly new style for an overtly new type of public amenity. Completed a decade before the founding of the NHS, Finsbury Health Centre was such a beacon of optimism that it featured on wartime propaganda posters as a symbol of the prosperity that could await if the Nazis were defeated. “Your Britain – Fight for it Now”, ran the caption – the future was bright, public and modernist.

A century later attitudes to modern design in the UK have changed. Far from representing a future so inspiring that we might give our lives to defend it, many Brits have come to resent contemporary architecture and look on the infrastructure, towers and estates created in the decades since Lubetkin as “eyesores”. Nowhere is the contempt for modern buildings more acute than in social housing estates, which are routinely criticised, maligned, neglected and demolished.

The government has now announced it will build 180,000 new social rent homes, but will this new generation of much-needed housing inspire more animosity or renewed appreciation? How did the reputation of public housing in Britain get so bad, and what can be done to improve the quality of social housing in the future?

After the second world war the UK embarked on an epic programme of investment. The new Labour government built hospitals, schools, roads, railway stations and thousands of new homes. So widespread was the consensus that Britain needed state-led renewal to recover from the war that the Conservatives continued Labour’s strategy when they returned to power. In 1963 Tory housing minister Keith Joseph declared: “The only answer is more houses”, promising his party would build 400,000 homes a year.

The unprecedented enthusiasm for building allowed the creation of some extraordinary projects that genuinely transformed lives from Lillington Gardens and Dawson’s Heights in London to Park Hill in Sheffield and Byker Wall in Newcastle. But the building boom delivered a fair share of duds too. Patrick Keiller’s 2000 film The Dilapidated Dwelling explores how an eagerness to hit government-mandated housing targets, mixed with corruption and a lack of proper oversight, allowed numerous large tower blocks to be built to abysmal, and ultimately unsafe, standards. Tragedies such as Ronan Point, which saw five people killed after poor design and construction caused multiple floors of a new East End tower block to partially collapse following a gas explosion, severely knocked confidence in new public buildings, especially housing.

An endemic lack of maintenance also sullied the reputation of social estates. The late architect Neave Brown confessed it had simply never occurred to him that the council would renege on their promises to maintain the buildings he designed for them. “The idea was that the concrete would be cleaned regularly,” he explained in 2015 at an Architecture Foundation event discussing the once dazzling white Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate Brown he’d built for Camden in 1969. “There would be a programme set up for proper maintenance and intensive cleaning as required.” Over five decades on, the estate hasn’t been properly cleaned once. So many once chic buildings of the 20th century have suffered similar decline, as years of grime, stains, bodged repairs and unthinking alterations have chipped away at their appeal.

There’s also been an attempt to scapegoat social housing. Politicians of all colours have found it convenient to claim crime and deprivation are the result of bad architecture rather than symptoms of their own policy failures. It was no coincidence, for example, that in 1997 Tony Blair used a visit to the postwar Aylesbury Estate in south London to criticise what he called “an underclass” of welfare claimants in his first public speech after winning the election. If Blair had taken a genuine interest in the estate, which was designed by Hans Peter Trenton, he’d have found generous apartments with panoramic views, multiple communal green spaces and a strong community. Instead, the former prime minister was happy to use the estate (and by extension social housing everywhere) as shorthand for fecklessness and social decline, allowing negative perceptions of social tenants and their homes to further ferment.

Today, the few councils and housing associations still building new social housing stock seem to have almost no ambition for the buildings they’re commissioning. Much new council housing is extremely poor: badly built, generic, characterless architecture with no sense of craft, place or personality. Many wonder why building more inspiring and well-made social housing is so hard.

But the blunt answer is that with an ounce of political will, high-quality social housing not only can be built, but frequently is.

Step across the Channel you’ll find that our neighbours are doing things very differently. In Paris, for example, mayor Anne Hidalgo has made housing a key priority. Ten years into her mayoralty, the city is starting to bristle with excellent and ecologically sound social housing schemes: a scalloped limestone apartment block in the sixth arrondissement; a seven-storey tower wrapped in colonnaded white balconies; a new scheme of 297 low-carbon timber apartments currently under construction.

If Paris alone suggests social housing can be sustainable and beautiful, Vienna proves it. The capital of Austria has a long-term strategy of commissioning outstanding social housing and now boasts some of the most remarkable and affordable contemporary homes in Europe. Alterlaa, for instance, is a 24-hectare neighbourhood of 3,200 homes arranged in three mountainous spines surrounded by public parks. Completed in 1986 and designed by Harry Glück, the blocks are lusciously verdant – each flat equipped with bathtub-like planters big enough for flowers, vegetables and even small trees. The estate has churches, shops, nurseries, 20 saunas and 14 swimming pools – seven of which are on rooftops.

Suggested Reading

The best hospital in the world

Vienna and Paris are wealthy cities but the impressive social housing being built in much poorer municipalities shows how proactive public sector leadership is ultimately more important when it comes to housing. Mallorca, for example, is now home to social housing of remarkable quality and vivacity. The Balearic Social Housing Institute (IBAVI) is a public agency designing housing projects and field- testing new methods and materials that can eventually be scaled up. The variety of social housing on the island is now so rich that IBAVI’s former managing director was awarded the RA Architecture prize – the first public servant to receive the honour.

Even in Britain decent new social housing is still occasionally built. Goldsmith Street, by architects Mikhail Riches, for example, is a pretty development of council homes in Norwich that won the 2019 Stirling prize. In Barking, a small and characterful block built in 2022 by Apparata proved exuberance can be achieved even within Britain’s miserly minimum space standards. And the warm-hearted buildings of Peter Barber Architects, masters of creating a sense of neighbourliness within substantial housing developments, are gradually multiplying.

Yet rather than working with some of the many careful and creative designers available, social housing commissioners in the UK too often opt for big profit-driven development partners who churn out uninspiring and generic buildings with no thought given to the communities they will serve or the neighbourhoods of which they are part. Frequently poorly insulated, prone to overheating, car-dominated and with minimal community spaces or amenities, the homes these large firms produce will do nothing to reverse the negative perceptions that still stalk social housing.

But by learning from the many exceptional new social developments springing up across Europe, and the visionary public sector bodies that enabled them, Britain could finally become a country where nothing is too good for ordinary people.

Phineas Harper is the director of Open City and a regular contributor to the Guardian