Human palaeontology – the study of the origin of humans from our ape-like progenitors – has occasionally been portrayed as the construction of grand narratives about the deep history of our species based on a single fossil tooth. That’s probably ungenerous, but the field certainly seems to offer support for the observation that scientific arguments increase in volume in inverse proportion to the available evidence. To outsiders, it can sometimes seem as though every fresh discovery of some new fossil hominid (the family of great apes, from chimps to gorillas to Homo sapiens) is greeted with the cry “This changes everything!”

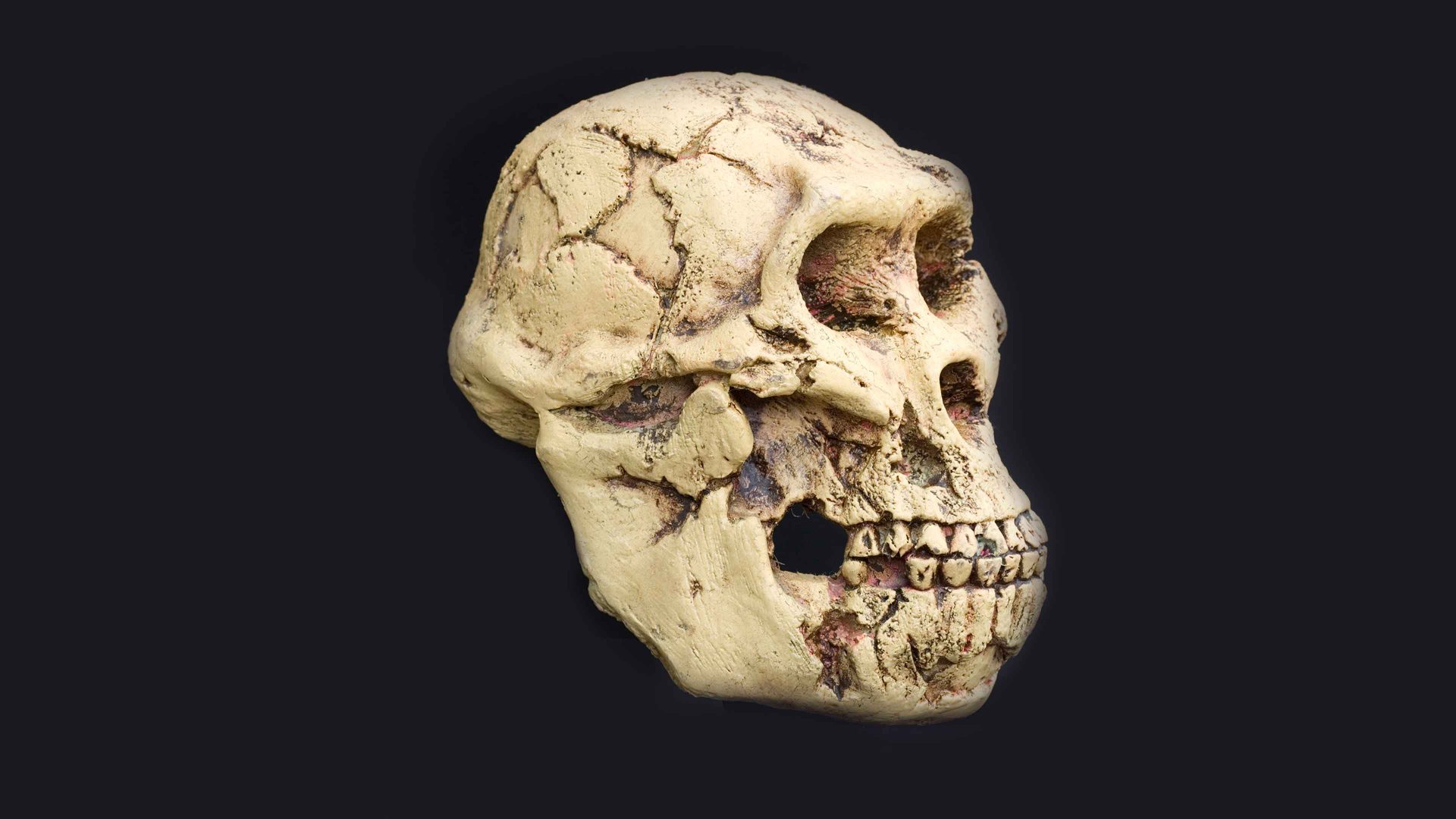

That was true of the discovery by Raymond Dart in 1925 of a fossil skull from Taung in South Africa that was interpreted as belonging to a small-brained human ancestor that walked upright (bipedal). This hominin (the lineage of great apes that we humans share with our closest ancestors, chimpanzees and bonobos) was named Australopithecus africanus. It lived between about three and two million years ago, long after our branch of the evolutionary tree diverged from that of chimps and bonobos. The big deal about A. africanus was not skull size – it didn’t have a big brain – but bipedalism. It suggested that the road towards humans began when our ancestors walked upright.

Dart’s claims were argued over for decades, and some features of A. africanus still aren’t agreed on. But fresh debate was ignited in 2001 with the discovery by French palaeontologist Michel Brunet and colleagues of a much earlier hominin, found in northern Chad and christened Sahelanthropus tchadensis, nicknamed Toumaï. This one was seven million years old, coinciding with the period when humans diverged from chimps and bonobos. That made things complicated. Was this the ancestor of all humans, as Brunet claimed, or instead of chimps, or perhaps even, as some suggested, of gorillas?

Suggested Reading

Driverless cars are coming. But can we trust them?

A key aspect of the debate was the claim that Toumaï too walked upright. How could you know something like that just from a skull? It’s a question of how the head was carried: did it look like one that looked straight ahead, like a biped, or was it adapted to a more horizontal body posture like that of a four-limbed walker? The distinction is blurry anyway: chimps, gorillas and other primates can walk on two legs but more normally use all four in knuckle-dragging fashion.

To do more than speculate, we needed more of the creature’s skeleton. Limb bones – a femur and ulnae – were found alongside the skull but were originally thought to be from a different, non-hominin creature. Over the years, however, they have come to be accepted as bones of S. tchadensis after all – albeit not without more fractiousness. Do these look like those of a tree climber, a quadruped walker, or a biped? Even if the creature walked on two feet, did it do that in the trees or, as a true human ancestor would, on the ground? Those arguments have raged, rancorously, for more than two decades. They erupted afresh in 2022 when Brunet claimed that the bones supported bipedalism, only to have the idea trashed by the researchers who had first identified the limb bones as also belonging to S. tchadensis.

All we have to go on here are comparisons with today’s apes (including us), which of course have all evolved in their own directions for millions of years and so are imperfect comparators. It’s a matter of interpretation – or some might say, of who shouts loudest. In 2023 a team led by Scott Williams of New York University argued that the ulnae and femur supported the hypothesis of knuckle-walking bipedalism, only to for veteran palaeontologist Bernard Wood of George Washington University and his team to gainsay them.

Williams and colleagues have now struck back with a new analysis of the limb bones, which they say do after all supply evidence that Sahelanthropus was bipedal. Sure, the bones look like those of chimps, the researchers say, but they have two features related to the way the hips and knees work that are found only in bipedal hominins like Australopithecus – even though the way they walked would have differed from that later species. The researchers say, for example, that the femur is twisted such that the leg points forward, as it would in bipeds.

The heat of the debate has been a little lower this time round, but there’s still not much sign of consensus. In the end, it’s unlikely that the bones currently available will settle anything – we need more fossils. It’s anyone’s guess whether more searching in Chad will oblige, but that’s the plan.