It seemed that peak flu had passed in the UK for this winter. The number of positive tests peaked in the first half of December and was dropping by week 51, and the number of hospital cases was falling as 2026 began. While some healthcare professionals warned that the cold snap could add to the pressure on the NHS, there was good reason to suppose the worst was over, although last week there was a sharp rise in cases again following two weeks of decline.

But in the end the worst was, apparently, not so bad. Over the Christmas week, the number of flu patients in acute hospitals was lower than in 2024-25, and barely more than half that in 2022-23. So whence all the fuss about “super flu”?

Public messaging about seasonal flu is tricky to get right. Influenza can be lethal, especially for vulnerable groups such as elderly people, but the number of flu-related deaths is hard to assess and hugely variable. In England, flu was implicated in more than 15,000 deaths in 2022-23, and almost 8,000 in 2024-25. But might all the dire warnings from the media and officials be counterproductive when things don’t turn out so bad, relatively speaking?

If you were lucky enough not to get a nasty bout of flu this season, recurring or dragging on for weeks, you probably know someone who did. But it’s not clear that this warranted the term “super flu”, as used by Keir Starmer and the health secretary, Wes Streeting.

The strains of virus going around this winter are all familiar: H1N1, H3N2, and influenza B. The talk was of a new variant of H3N2 called K, which the current flu vaccine was not designed to combat (although the vaccine offers some protection against it anyway). But K isn’t known to be more virulent, and has been recognised anyway for many decades.

Media alarm was driven in part by the timing. Flu cases were unusually high by the start of November, not because this season was worse than previous ones but because it came earlier. In recent years, cases have peaked in early January or, for 2023-24, in February.

It was reasonable to worry that, with things looking so bad already by the start of December, they could be worse still by the new year. But it was equally possible that this was a normal flu season that kicked off sooner.

Suggested Reading

The quest for artificial eggs

Flu seasons are always beset by imponderables, but – as is the case with future Covid-style pandemics – that makes preparedness all the more important.

It’s in this respect that there are lessons to be learned from this winter’s flu season. The main reason for concern about the ability of the NHS to cope was not that numbers of admissions would soar, but that hospitals operate at close to capacity as a matter of course. In its current state, the UK could never be ready for a bad year like 2022-23 (whether doctors go on strike or not).

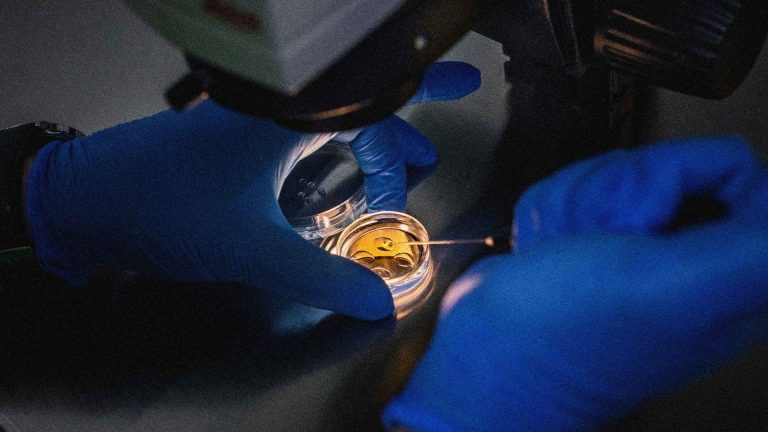

What’s more, stocks of vaccine were inadequate to cope with the demand from those paying for a shot at pharmacies. My own jab was delayed until the mid-December infection peak because my local pharmacy had been given a faulty batch and had to wait 10 days for replacements.

Vaccine take-up is not particularly high: in some groups, less than half of those eligible got a shot. Some of this is due to complacency – people do not tend to think of flu as life-threatening, but if you help to spread it, you put the truly vulnerable at greater risk. But we’re surely also still seeing the impact of post-Covid vaccine hesitancy, now abetted through robust misinformation networks.

There are also questions about the eligibility criteria: it seems absurd that the official messaging urges people to get a jab if they’re eligible while the rules are so restrictive about who is, given the cost of hospital admissions.

The annual guessing game about which viral strains to target – a decision that must be made well before the season begins – is a perpetual challenge. But this at least could be obviated in future by a universal flu vaccine, which several pharmaceutical companies are seeking to develop.

One strategy is to train the immune system to produce antibodies against parts of influenza viruses that don’t mutate much, rather than aiming at the more prominent parts of the virus that tend to rapidly evolve to evade an immune response. Some such treatments are in clinical trials, although the anti-vaccine crusade of US health secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr is threatening efforts at the US National Institutes of Health. It is surreal to witness vaccine research being actively undermined, but this is 2026.