During the Covid pandemic, Boris Johnson’s promise of a “world-beating” test-and trace system came to seem like a sick joke. But there was one respect in which the UK’s testing really did excel: analysing the viral genome in samples so that the emergence of new variants could be spotted quickly. This ability relied heavily on one laboratory: the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridgeshire. Over the course of the pandemic, the institute analysed more than 2m viral genomes in a round-the-clock operation. “We were watching the pandemic evolve in real time, hour by hour, as samples came in,” says the Sanger’s director of strategy, partnerships and innovation, Julia Wilson.

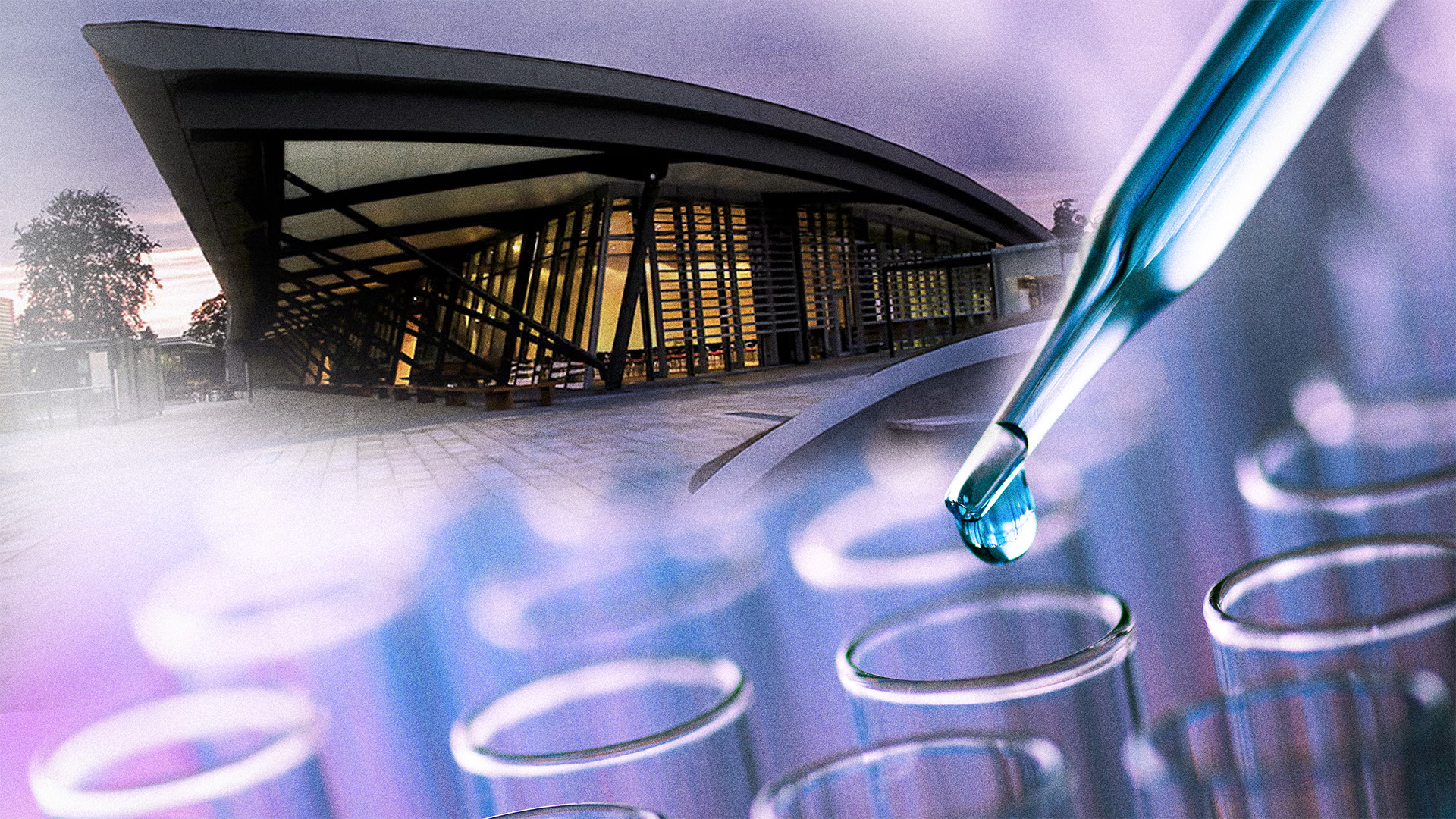

This remarkable feat was a dramatic vindication of the Sanger’s existence and its unique status, in between an academic research institute and an industrial lab. The keystone of the Wellcome Genome Campus near the village of Hinxton, in the countryside nine miles south of Cambridge, the institute is a cluster of modernist glass and concrete springing from the meadows around the River Cam.

The Sanger was founded in 1992, with funding primarily from the Wellcome Trust, to develop the large-scale gene sequencing technology needed for the Human Genome Project (HGP), the international initiative to read the 3bn-letter code (“sequence”) of human DNA. The institute is named after the British biochemist Fred Sanger, who won two Nobel prizes, the second in 1980 for developing key techniques used in genome sequencing. One third of the HGP sequencing was done at the Sanger.

It was always clear that the HGP would initiate a demand for more sequencing. The key to understanding our genome is to tease out the small differences in sequence between individuals so that we can see how different gene variants are associated with specific traits and diseases. That demands not just one reference genome sequence, but many thousands or even millions. No academic labs could generate data on that scale.

With that goal in mind, the Sanger was central to the international 1000 Genomes project that ran between 2008 and 2015 to collect and compare the genomes of “1000” (in the end it was just over 2,500) individuals, to identify common genetic variants in diverse human populations – “common” meaning that they are found in at least 1% of those populations. Impressive in its day, that effort pales in comparison with what is now possible: the Sanger has sequenced more than half of the half a million genomes stored in the UK Biobank repository, a collection of genomic material from volunteers. Data like this makes it possible to identify the genetic roots of many rare diseases associated with gene variants that only a tiny proportion of people carry, as well as showing how such variants are distributed across different populations.

It’s not just about data. Understanding the roles of genes in our constitution requires a huge amount of fundamental research. Using gene-editing methods to alter the genomes of individual cells, for example, can help to reveal how genes actually function and how they are linked to “phenotypes”: the characteristics of tissues and organisms. Such work is being done in university labs all over the world, but what the Sanger can offer is resources to pursue it on a larger scale. As well as having genome-sequencing facilities, the institute now possesses large-scale cell-culturing and gene-editing capabilities.

Thanks to such facilities, the Sanger plays a key role in the international Human Cell Atlas initiative, which seeks to map out all the cells in the human body and how they are arranged – a map that of course differs in detail for everyone, but shares the same broad structure. So far, the heart, lung, and placenta are among the tissues and organs that have been closely mapped, helping to understand the differences between healthy and diseased tissues at the cellular scale. Researchers at the Sanger also investigate the genomes of non-human organisms, from gorillas and dogs to antibiotic-resistant bacteria: information that can advance our understanding of evolution, biodiversity, and biomedicine. Cancers – how they develop, and how they can be combated – are a major focus of the research at the institute.

Wilson says that freedom from the academic treadmill means that the Sanger groups can take a much longer-term view, pursuing “decadal challenges that you can’t do in a university setting”. In this way, the institute has a “mandate to do science that no one else can do.”

“The HGP was the exemplar of a large-scale project that was hard to do in academia,” says the Sanger’s director Matthew Hurles, whose research team seeks to apply new genetic technologies to the diagnosis of rare genetic disorders. Research in university departments tends to be driven by hypothesis testing, the end product of which are academic papers. Thus “academia excels at doing deep but narrow research,” says Hurles. The Sanger, on the other hand, can focus on generating large data sets, like those now needed for AI, that drive the whole knowledge ecosystem forward.

Suggested Reading

The cancer vaccines under threat from MAGA

That’s possible because of the type of funding it receives. Academics must rely on grants, and can only conduct the projects that get funded. But the Sanger can be more strategic, because it has “core funding” guaranteed by Wellcome. Faculty leaders can decide on a programme and allocate resources in a top-down approach. “The director has the autonomy to look at what the world is doing and define strategic areas,” says Wilson.

This structure also means that the Sanger can pivot very quickly from one topic to another. “Wellcome wanted agility, political and financial independence,” says Wilson. That’s what made it easy for the institute to drop everything in the pandemic and devote its huge sequencing capability to analysing viral genomes.

Sanger researchers must, however, be on board with the mission, says Hurles – which won’t suit everyone. It doesn’t mean they get less autonomy than academics, he adds, but it’s a different kind of autonomy. “At the Sanger they get to do science that they can’t do elsewhere.” The institute currently has around 1,300 staff, which includes 30-35 faculty and principal investigators, between 80-100 PhD students and around 100 postdoctoral students. Group leader Emma Davenport says that one of the advantages compared with academia is the ability to hire new team members quickly and get working on a promising new idea right away, without having to go through the slow and painful process of applying for grants.

On the other hand there is no tenure for staff, and in the past the Sanger has suffered accusations of a lack of due process for hiring and firing, with some staff complaining that resources were allocated unfairly and feeling that “the axe can fall at any time”. There were also accusations of bullying and harassment, leading to an independent investigation in 2018 that cleared the institute of wrongdoing but called for more transparency in decision-making.

Suggested Reading

Epstein and the moral rot of US public intellectuals

It’s perplexing that the Sanger’s model is not adopted more widely. Universities are an invaluable source of ideas and discoveries, but some objectives, especially in the life sciences, demand repetitive work that doesn’t attract academic kudos. The commercial sector can be good at turning basic science into useful applications, but in a narrow and market-driven way that doesn’t necessarily serve key societal needs. The Sanger aims to translate discovery into genuinely useful procedures before “passing the baton on to pharmaceutical and biotech companies,” says Wilson. “We deliberately democratise discovery, then move on.”

There are efforts internationally to fill this same gap: leveraging basic science to produce socially useful capabilities and applications and generating knowledge that is valuable rather than glamorous. Germany positions its Fraunhöfer Institutes, funded by government and industry, somewhat in that space. The United States, with a long tradition of philanthropic funding for non-profit research, has centres such as the Salk Institute in California, the Janelia Research Campus in Virginia, and the Broad Institute, affiliated with Harvard and MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts. And since 2016 the Francis Crick Institute in London has served as a hub of biomedical research funded by the UK’s Medical Research Council and the charities Cancer Research UK and Wellcome, although Hurles says it operates rather closer to an academic model.

Among its projects, the Sanger Institute has worked closely with Genomics England, affiliated with the NHS to work on genomic diagnostics of disease. “One hundred and forty-five families have received rare-disease diagnosis due to a new method developed at the Sanger,” says Wilson. Davenport has been collaborating with the Rosie Hospital, part of Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, to predict pregnancy outcomes and complications from genetic analysis.

It is hard to get this kind of institute right. Hurles notes that comparable institutions in the US, such as the Allen Institutes for Brain and Cell Science in Seattle, tend to be younger than 30 years or so. After a time, he says, it seems very hard to resist the “gravitational pull” of the academic system, with its rigid departments, publications-driven incentives, and dependency on grants. The UK hasn’t traditionally been very good at setting up research institutes that deviate from the standard academic model. The Alan Turing Institute, established in 2014 as a hub for research on AI, became an awkward halfway house, lacking any centralised base and staffed by fellows from academia. The result was institutional bickering over funds and a tendency for staff to do their own thing rather than collaborate; the institute is now in crisis.

The lack of institutional diversity in the UK was highlighted by the 2023 report on research, development and innovation headed by Sir Paul Nurse, director of the Crick Institute. “In academia, the sizes of teams, budgets, and projects are similar,” says Hurles. But there are surely many ways to produce useful knowledge. “I’d love to see more unconventional institutions like Sanger in the world,” he says. It’s not a bad idea.