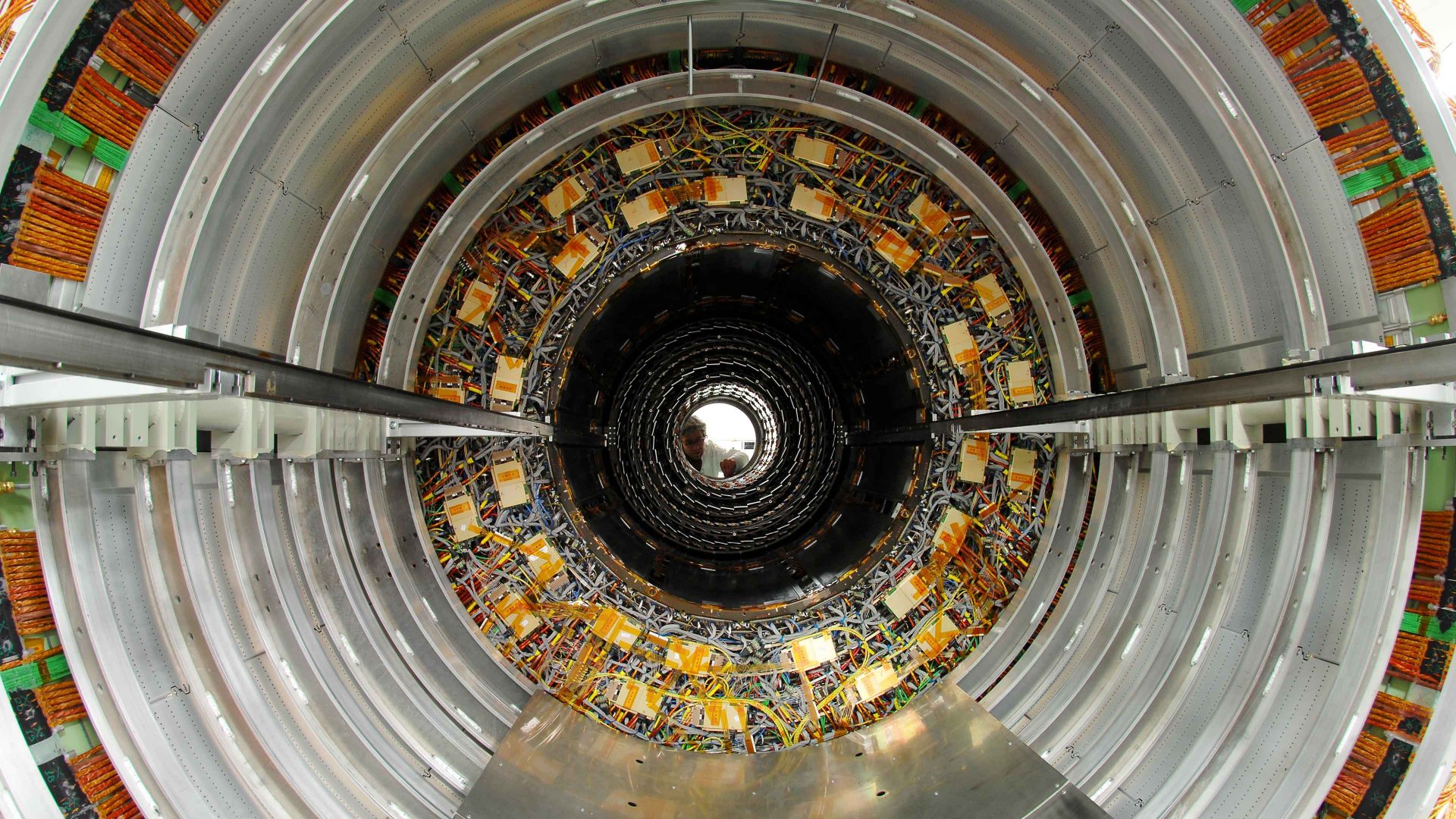

Cern, the European centre for particle physics, is exploring the feasibility of a new circular collider to push high-energy physics beyond the limits reachable with the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which is currently the world’s most powerful particle accelerator. The LHC is housed in a tunnel 27km in circumference, close to Geneva in Switzerland. Particles in the proposed Future Circular Collider (FCC) would make a 100km round trip: the LHC is a mere napkin ring to the FCC’s dinner plate.

The feasibility study for the FCC began in 2021 after being recommended in the 2020 update of the European Strategy for Particle Physics; the results of the study are due in 2027. If the project is found to be acceptable not just on scientific grounds but also in terms of the engineering challenges, environmental impact and cost, construction could start in the late 2030s with a view to having the device operating by around 2045. A second circular collider might then be added in the same 200m-deep tunnel (which would extend over the border into France) in the 2070s. Cern says that such a massive machine could keep particle physicists busy well into the next century.

But is such an immense undertaking justified? Is it reasonable for particle physicists (who are a minority of the entire physics community) to go on demanding ever bigger instruments? Not everyone thinks so, especially because the LHC itself has not yet produced the kind of breakthrough results (beyond proving the existence of the Higgs particle in 2012) that some had hoped for. The problem is that there are some areas of science, especially in fundamental physics, in which gargantuan instruments seem the only way forward for studying the universe. Advocates say the FCC could answer burning questions about dark matter, quantum gravity, the imbalance of matter and antimatter, and the mysterious particles called neutrinos.

Circular colliders are devices for smashing fundamental particles into one another at enormous energies. The particles are guided along circular trajectories by magnetic fields, while being given electromagnetic kicks on each circuit to increase their speed. They typically approach the speed of light – the cosmic speed limit – before colliding. The proposed FCC would create collision energies almost 10 times greater than those of the LHC.

Suggested Reading

The deepest view into the universe yet

The higher the energy, the more we can hope to see. Higgs particles, for example, will only form in collisions as energetic as those of the LHC. To put it another way, accessing higher energies allows scientists to probe ever smaller length scales and thus to see the physical world at an ever finer grain. The first particle accelerators were used to give particles enough energy to blast their way into the atomic nucleus and reveal what is inside. Today’s higher-energy accelerators can probe the inner structure of the fundamental particles themselves, such as protons that make up atomic nuclei. By crashing electrons and protons into one another at unprecedented energies, the FFC would examine even smaller scales.

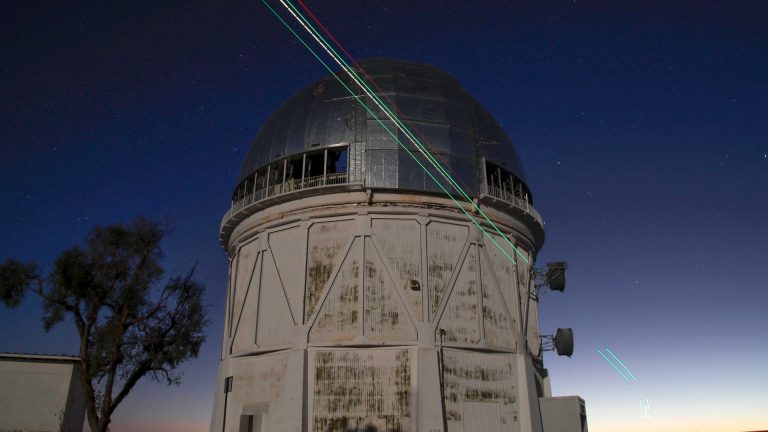

Other scientific instruments have to be huge for other reasons. The bigger a telescope is – the wider, say, its light-focusing mirror – the more light it can gather and so the further afield in the cosmos, and the dimmer the objects, it can see. The largest of today’s telescopes have mirrors around 10m across, although by joining individual telescopes via satellite telecommunication networks we can in effect create a kind of observing device thousands of kilometres across. There are plans to make much larger mirrors, most notably that of the gauchely named “Extremely Large Telescope” in Chile, due to be completed in 2028, which will have a 39m diameter. The installations housing and controlling these reflectors are of course immense too.

Meanwhile, gravitational-wave detectors such as LIGO in the US have channels several kilometres long, down which light beams are bounced off a mirror at the far end. Tiny changes in the lengths of two such channels at right angles, due to the passage of a gravitational wave (GW), cause interference of the light beams, which signals the passage of the wave. The longer the arms, the more sensitive the detector, which is why the European Space Agency plans to construct a GW detector in space with arms 2.5 million km long. The light source and mirrors would be carried by spacecraft orbiting the sun, the light beams travelling through empty space between them.

It seems ironic that the more deeply we want to see into the world, the bigger we have to make our instruments. But often that’s just how the physics works. The question is whether the intellectual returns from such huge projects justify their ballooning costs.