If a spacecraft were to land on Jupiter’s moon Europa, where an ocean of salty water apparently sloshes beneath the icy crust, and search for signs of life, what would it look for? If it were to photograph fish swimming under the ice, there’d be little to argue about.

But you’d be hard pushed to find an astrobiologist – the scientists who think about life on other planets – who expects to see big animal-like organisms anywhere else in our solar system. The best we might hope for is something like a microbe. But it might have totally different chemistry to life on Earth – no DNA, no proteins – and might not look anything like life as we know it. How then could we be sure that anything we might detect would even qualify as life?

We couldn’t: for there is no agreed scientific definition of life that can be brought to bear. This lack of consensus is apparent in a recent paper (not yet published) by a team of researchers that includes the US biologist Michael Levin and computer scientist Blaise Agüera y Arcas, an AI researcher at Google, titled What lives?

They asked 68 selected scientists and philosophers who have thought about the issue (full disclosure: I was one of them) to offer a definition of life, and then ran the results through a large language model to look for common themes, concepts and words.

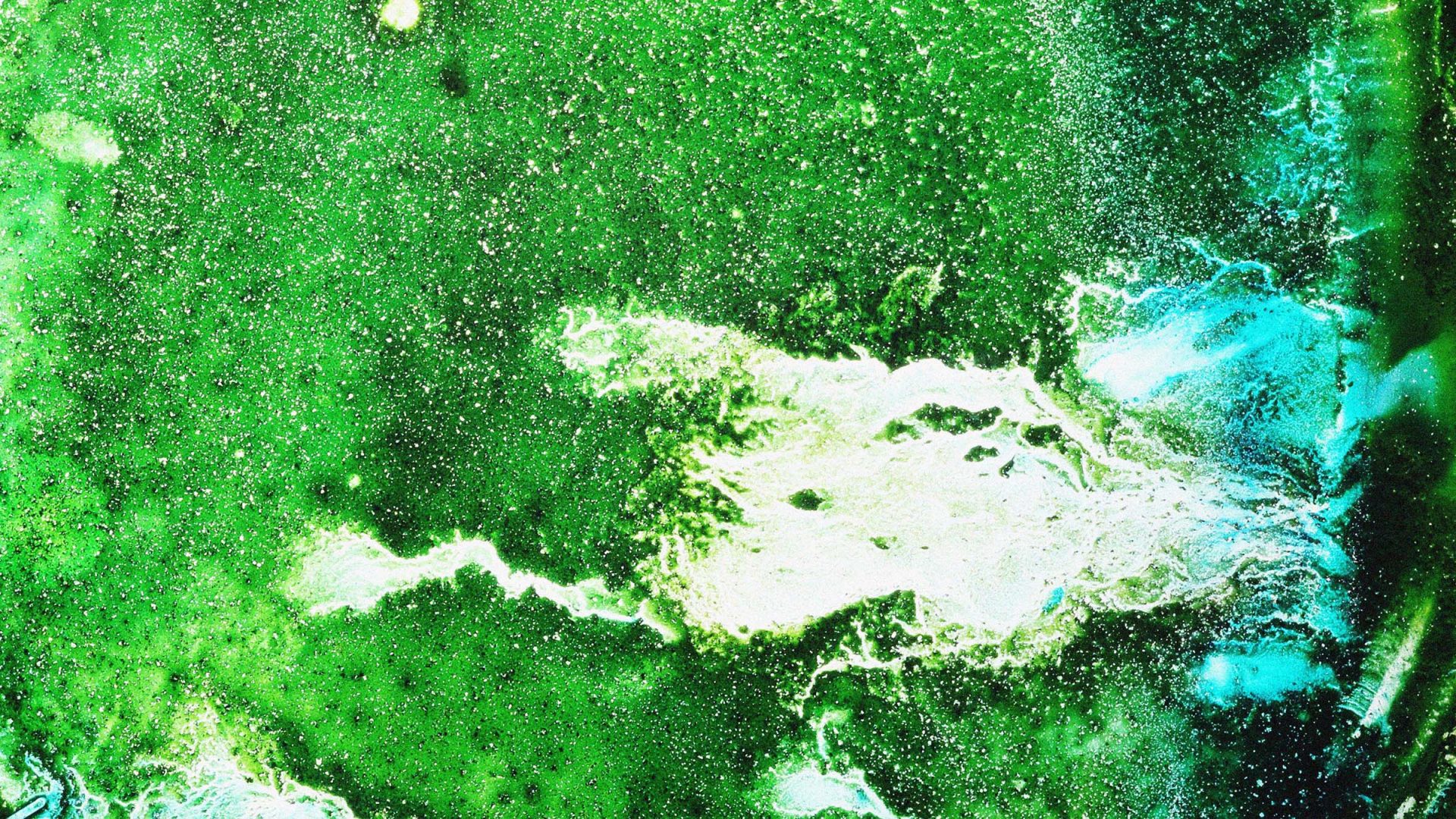

The AI boiled the answers down to a set of points on a two-dimensional graph that represents a kind of map of the “concept space” of life. You could think of the position of each point as an indicator of how much importance that person places on, say, the idea that life must show something like cognition, or be able to replicate and evolve, or resemble life as we know it.

The coordinates of the 2D plot are a mash-up of many such variables, with no obvious interpretation in their own right. But they offer a snapshot of the diversity of thinking among the respondents, showing how close or far each person’s views are from the others. (No two definitions were identical, or were deemed equivalent by the AI.)

Such differences are no surprise. Agüera y Arcas, for example, has reported simple computer programs that, simply by being able to interact and to mutate, develop the ability to self-replicate. Does that superficially mimic life, as computer games do, or is it a genuine form of life itself? That depends on what you mean by “alive”. To my mind the notion of life becomes too shallow if it can include bits of computer code – but I’m now reminded that I’m just one point in the landscape of opinion.

Suggested Reading

Why we need to be more chill about language change

The question “what is life?” is ancient and universal. Some cultures and traditions don’t confine life to the things biologists study (bacteria, blue whales, beetroot) but extend it to rivers and mountains. Only in the 19th century did scientists become pretty sure there is no vitalistic “essence” distinguishing the living from the non-living.

But they’ve been scratching their heads ever since about what then seems to make these entities distinct, if both can be reduced at some level to the principles of chemistry and physics.

The 1944 book What Is Life? by physicist Erwin Schrödinger inspired Francis Crick and James Watson to seek an answer in DNA, where Watson thought, wrongly, that they’d found it. Nobel laureate biologist Paul Nurse offered an updated tract with the same title in 2020 but was characteristically modest about how much of an answer he could really give. The paper by Levin and colleagues confirms that his humility was wise.

This sort of thing is bread and butter to the philosophers of biology in whose company I am spending the week at an international conference on the subject in Portugal.

It’s not angels-on-pinheads stuff. Finding life on another planet, quite apart from being front-page news, would profoundly impact our sense of place in the universe. Just one such detection would – given that we’ve only surveyed a negligible fraction of the planets that exist – imply that life is common throughout the cosmos, making it feel a little less lonely on our blue dot (or, some might argue, a little less safe).

Knowing something about alien life could very well offer clues about how life started on Earth. But right now, we can’t be sure that, even if life were staring us in the face on Europa, we’d recognise it as such.

Our view is inevitably Earth-centric: if life is not as we know it, we might not even call it life.