Listening to great music is always a deeply satisfying experience, but what if the music is also listening to you?

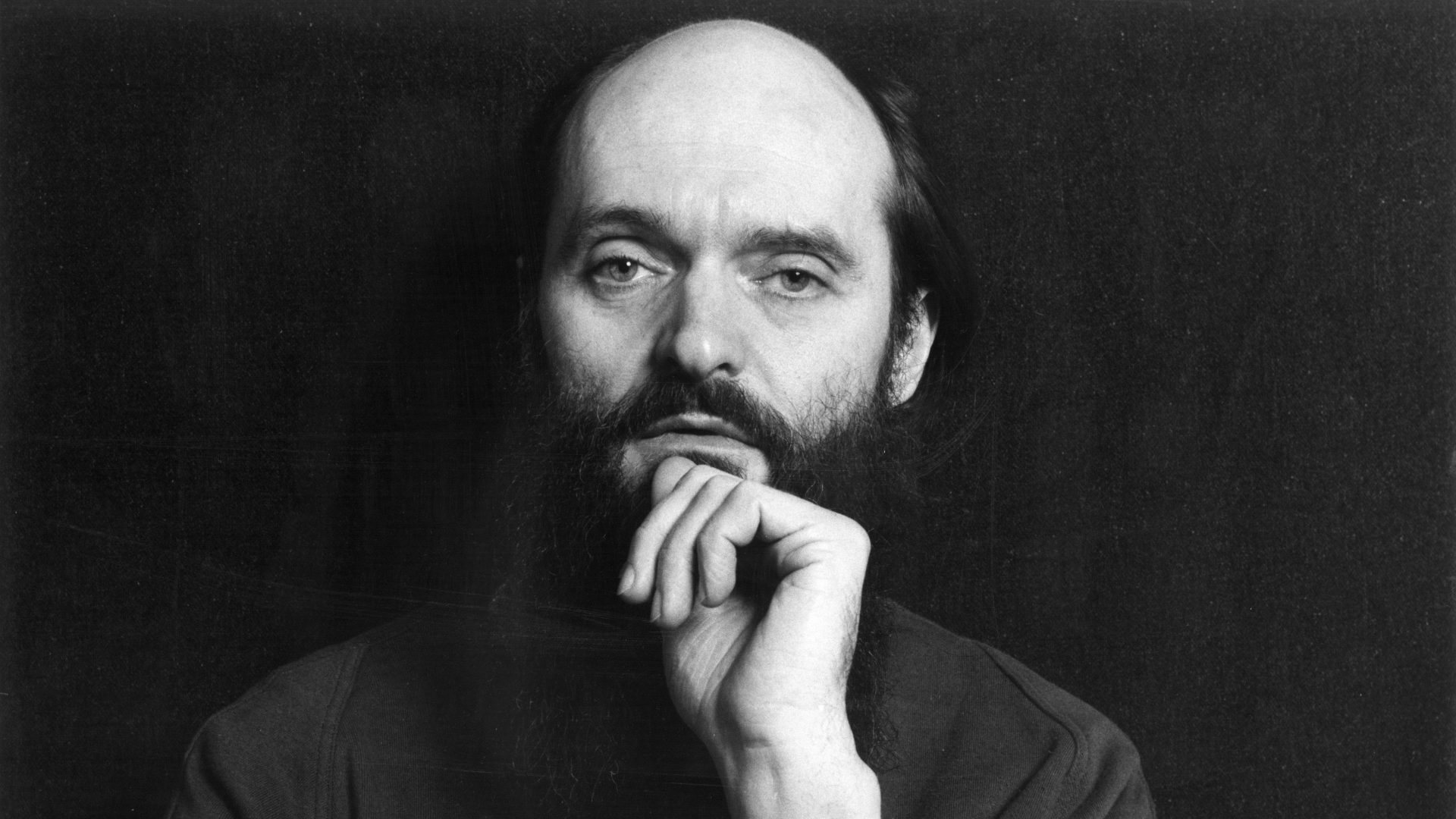

This is an idea suggested by the Grammy award-winning conductor Tõnu Kaljuste, perhaps the world’s leading interpreter of the work of contemporary Estonian composer Arvo Pärt (pronounced “Pairt”). Such is Kaljuste’s faith in the healing power of Pärt’s music that he believes there is a mysterious, reason-defying interaction between it and the listener. “Arvo Pärt’s music was like medicine for me, when I first heard it. It’s very personal. Doctor Arvo Pärt makes me feel well!”

September marks the composer’s 90th birthday. According to Bachtrack, a classical music website, he has been the world’s most-performed living classical composer since 2011, apart from a brief interlude when he slipped below the American John Williams.

Pärt’s birthday milestone is important not only because of his commanding position on the world stage, but because he is one of the few living composers to have developed his own compositional technique, which he calls tintinnabuli – “like the ringing of bells”. This strictly organised, mathematically based system is designed to reduce music to its essential elements: “Minimum is maximum,” as Tõnu Kaljuste puts it.

Listening to these intense, meditative pieces, you hear affinities with the modern minimalism of Philip Glass, and simultaneously, echoes of the 16th-century English composer Thomas Tallis. It’s music that also has something in common with the work of John Tavener, the great English minimalist. It seems no coincidence that both Pärt and Tavener became adherents of the Orthodox church during the 1970s.

Perhaps it’s also no coincidence that this decade was an exceptionally fertile period for Pärt. After spending many years studying medieval and Renaissance music, he began composing religious works in the late 1960s, when Estonia was still under Soviet rule. Some of his close relatives had been among tens of thousands sent to Siberia on Stalin’s orders. Pärt began looking westward for inspiration.

His compositional style first began to blossom when he was studying under the Estonian composer Veljo Tormis, who wrote hundreds of songs for choirs based on traditional folk songs, or “runic” songs. But Pärt gradually evolved his own very different approach.

Some of his music, such as the piano/violin duet Spiegel im Spiegel (Mirror in the Mirror, 1978), sounds childlike in its apparent simplicity – in this case, the violin plays slow, repeated rising and falling melodies up and down the scale, as the piano picks out simple triads. Like most of Pärt’s music, the piece exerts a hypnotic quality. Typical is Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten (1977) in which, to the tolling of a tubular bell, the strings slowly descend and overlap like ocean waves.

Suggested Reading

Oasis have returned when we need them most

The religious focus of Pärt’s work was at odds with Estonia’s official atheism, and resulted in fewer performances of the music. In 1980, Pärt and his family were finally allowed to leave the country, and they moved to Vienna.

The timeless quality of compositions like Tabula Rasa (1977) gradually turned him into a global star. The catalyst was Manfred Eicher, founder of the German ECM record label, who was driving late one night from Stuttgart to Zürich when he heard something on the radio that sounded to him like “angel music”.

Eicher turned off the autobahn and drove to a nearby hilltop where the reception was better. After listening for half an hour, he immediately knew he had to record Tabula Rasa, although at the time he had no idea who had composed it.

The record came out in 1984, and Pärt has been with the label ever since. A nurse in a New York hospital Aids ward reportedly used to play it for the dying young men, and in their final days they would ask for it repeatedly.

A more recent work, Adam’s Lament (2011) for choir and orchestra, shows a further evolution in style. Superficially, this is a piece of work that might have been written at any time in the last 150 years, with its chanting Greek or Russian Orthodox choral style, but structurally it sounds different from what had gone before.

The continued popularity of Pärt’s music is clear from the fact that more than 600 concerts are in the international calendar during 2025 and beyond. Tõnu Kaljuste’s punishing performance schedule with the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir (EPCC) – the world’s leading performers of this music – has so far taken him to France, Belgium, Germany, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, and to China later in the year. At the end of July, Kaljuste conducts several pieces by Pärt at the BBC Proms. There are further gigs to come in the UK – at the Aldeburgh Festival (August 1), and later in the year at Glasgow City Halls and London’s Barbican Centre.

Meanwhile, ECM have recently issued a double vinyl LP, Tractus, featuring the EPCC and the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Tõnu Kaljuste and produced by Manfred Eicher.

While the romantic composers aim straight for the heart, composers who take a more abstract approach can stir hidden depths. “Pärt keeps some distance, always,” says Tõnu Kaljuste. “When you play certain pieces by JS Bach, you feel that the composition keeps some distance from you. It’s not describing straight emotions. Sometimes it’s connected with algebra, mathematics.”

Peter Jones is a jazz musician, journalist and author