“I’m worried about going out. I’m even more worried for my little brother, who’s 14. Everyone thinks they’ve got to carry a knife to protect themselves. It’s dangerous.”

This was break time in one of our workshops. A group of 10 young lads puffing on their vapes in the small garden outside the hall.

What these young people were telling us, we heard again and again across the country. We have spent the last year talking, and more importantly listening, to more than 700 young people between the ages of 16 and 18 about their hopes and fears.

We come from two very different backgrounds – a mid-50s, white, ex-headteacher and former adviser to Tony Blair and Keir Starmer from London, and a mid-20s, black, researcher and mentor from Manchester. Both of us were determined to get beneath the screeching headlines, the moral panic, and the patronising condescension shown to young people. Our report, Inside the Mind of a 16-year-old, published this week by Demos, does exactly that.

Young people did not just see knife crime as a political issue or something they had read about online, it was personal. Politicians’ failure to act on it was a symbol for young people that they don’t care – or if they do care, they don’t deliver.

From Bristol to Oldham to Sunderland to Birmingham, young people talked about carrying a sense of anxiety, of looking over their shoulder on the way home, of knowing which streets to avoid, of having fewer and fewer places to go where they could relax without worry.

When we dug deeper, it became clear that knife crime and the fear surrounding it was often a symptom of something broader: the collapse of social spaces for young people. When asked what would help, young people didn’t just say more police. They talked about youth clubs that had shut down, libraries that no longer felt welcoming, parks that felt unsafe after dark and leisure spaces that were unaffordable. One student put it like this: “You can’t complain that young people are always online if there’s nothing for them to do offline.”

On the train back from the workshop, we debated what we had heard:

Shuab: Peter, you’ve worked for Keir, tell me why he doesn’t care more about knife crime.

Peter: He does, only the other day he had Idris Elba around the cabinet table discussing it.

Shuab (laughing): Idris Elba, the representative of Gen Z! No one knows who he is. He was definitely famous for my aunties’ generation, because he was in The Wire and kind of for my generation because he was in Luther. But a 16-year-old wouldn’t have a clue who he was.

Peter: But at least he raises the profile of the issue.

Shuab: Great! And for women’s sexual health, I suppose we’ll get Judi Dench to talk to 16-year-old girls.

Those train journeys were a chance for us to reflect on what appeared to be a growing gap between generations.

Moral panic is nothing new. In fact, it’s very much the norm. Every few years, it cranks up again.

Some will remember rave culture in the late 1980s being condemned as a “sinister evil cult”. Or hoodies in the 1990s being described as “gangs of feral youths and yob culture”. Or the panic over a “happy slapping” craze 20 years ago.

Suggested Reading

My best friend’s murder

Today that panic is in overdrive, fuelled by screaming headlines about Gen Z, irresponsible dramas like Adolescence playing on the fears of parents, and an online world that older generations seek to condemn before even attempting to understand it.

And this moral panic is a bit rich coming from politicians and policy makers who have got it so badly wrong. Who have reduced education in schools to an exam factory – and last week, in the government’s curriculum review, also refused to do anything about it. Who have put housing out of reach of first-time buyers so that 30-year-olds are still living at home with their parents. Who have delivered a triple lock for pensioners, and at the same time a triple fear for young people: fear of knife crime, fear of not getting a job, fear of the future.

This needs to change. Not just because 16-year-olds are about to get the vote and need to be taken more seriously, but because this is the first generation in history who are destined to be poorer than their parents. That is the real national emergency.

And if we continue to do so little to help young people get their future back, it will be no surprise if their despair pushes them into the arms of the populists.

To be honest, it is already happening across Europe. Populist parties used to be brimful of ageing fascists, but are now being given a new lease of life by disillusioned young people.

There are two problems. And they are linked. There is a meagre policy agenda tailored to the needs and aspirations of young people. And the mainstream political class is hopeless at communicating with them.

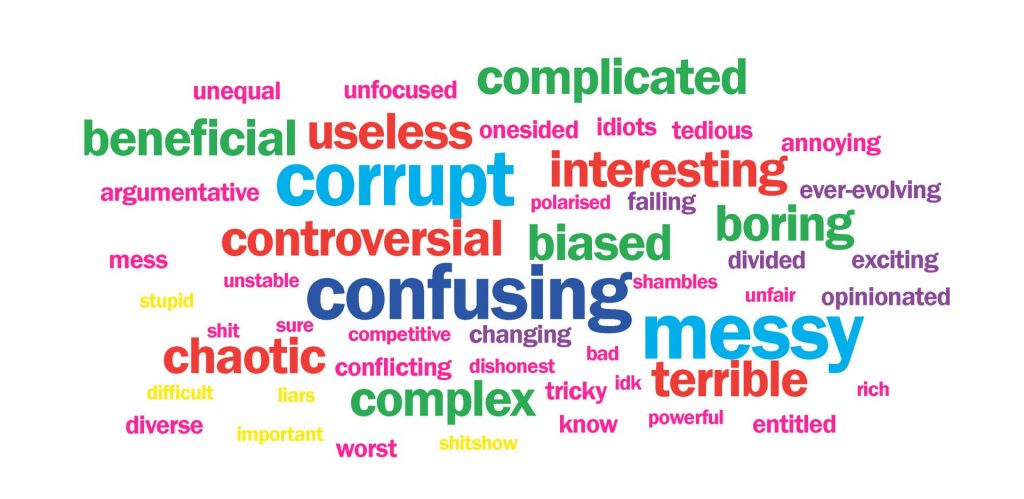

When we asked young people about the state of politics, a loud blast of disapproval came back.

“Politics feels more like a circus. Politicians are too busy arguing and calling each other corrupt to fix anything that matters,” said one student in Bristol.

They spoke clearly about feeling exhausted by constant crisis management and superficial political battles.

As 16- to 18-year-olds, the government for them is having six prime ministers in nine years. From our conversations it became clear that what they want is not authoritarianism or less democracy, it is a democracy that delivers tangible improvements in their lives.

When asked explicitly about the changes they would like to see, students articulated clear priorities for democratic reform. Crucially, these demands went beyond surface-level changes:

Accountability and integrity: young people want politicians held genuinely accountable for mistakes. A student from Oldham stated plainly: “If they break promises, there need to be real consequences.”

Genuine responsiveness: rather than symbolic gestures, students wanted practical improvements in areas such as housing affordability, education, mental health and climate change. “Stop arguing about Brexit and sort out affordable housing,” said one from Uxbridge.

Political stability and focus: they wanted an end to constant infighting and scandal. “Headlines shouldn’t always be about political drama,” said a student from Bristol. “They should be about fixing the country.”

Young people’s vision for democracy was fundamentally practical, realistic and achievable. They are not expecting a utopia.

Suggested Reading

The locked-in generation

One of the most revealing themes to emerge from our workshops was how deeply the idea of “strength” resonates with young people. A sense that a leader knows what they believe, speaks clearly and acts quickly. In a political landscape often defined by dithering, U-turns and spin, this kind of clarity is magnetic.

Donald Trump and Nigel Farage came up repeatedly in conversations, not always with approval but often with a kind of reluctant respect. It was not necessarily about liking them or agreeing with their views. It was that they seemed confident, unapologetic and clear in what they stood for.

For many young people, especially in contrast to more conventional politicians, Trump and Farage gave the impression of being in control. A teenager in Oldham explained it plainly:

“Trump says things and then does them. Or at least it looks that way. Politicians here just argue.”

Across the country, we heard strikingly similar views. Trump was frequently described as bold, unapologetic and “not afraid to make enemies”. Farage, meanwhile, was seen by many as one of the few UK politicians who “says what he actually thinks”.

“Even if I don’t agree with him, at least he says what he means. You don’t get that with most politicians,” said one.

Farage’s appeal was not necessarily about political alignment. In a field of politicians whom students often struggled to describe or differentiate, Farage stood out. They could tell you what he thought, they could tell you what he said.

“Farage is the only one who sounds like he actually believes what he’s saying,” a student from Sunderland told us. “Everyone else sounds like they’ve been told what to say by some committee.”

Others were more critical, but still acknowledged his appeal. One student in Wigan said: “He’s not likeable, but you know where he stands. That matters.”

Most of our conversations happened before Zack Polanski came on the scene, and we believe there would be a similar reaction to him.

Traditional politicians are increasingly seen as indistinguishable from one another. Several students admitted they did not trust Trump or Farage, but still admired the way they communicated.

“It’s not about facts. It’s about energy,” one student in Uxbridge said. “Trump and Farage come off like they actually want to fix stuff.”

The appeal of these figures is not necessarily a rejection of democratic values. It is a reaction to how democracy is currently functioning. After years of political chaos, party scandals and economic stagnation, many young people have grown sceptical that traditional processes can deliver change at all. Figures who project strength, even if it’s just a carefully maintained image, are filling the leadership vacuum left by cautious centrism and institutional paralysis.

This is not the same as support for authoritarianism; students were clear-eyed about the risks. But the attraction to “strength” reflects a hunger for conviction, a longing for action in a climate dominated by hesitation.

What makes this even more striking is how early this scepticism takes root. Many of the young people we spoke to have not even voted yet and already a significant proportion are convinced that politics in Britain is broken.

The danger is not that this generation has given up on democracy. It’s that if nothing changes, they might stop believing democracy can work for them at all.

For many, there was real affection for British values like fairness and free speech, and institutions such as the NHS. But that sat alongside a deep sense of unease about the cost-of-living crisis, political sleaze, broken promises and the feeling that this is a country where success depends too much on where you are born.

There was a sense that politics had become too performative and that many politicians were more interested in superficial communications than in addressing the structural issues facing their communities. Rather than disengaged, these young people were reflective and realistic, hopeful that things could improve, but unconvinced that those in power were willing or able to make that happen.

Just imagine if the government had said “we want to take money from wealthy pensioners and put it into supporting the next generation – to tackle knife crime, the cost of living, to provide homes, to address mental health, to ensure every young person has the education they need to thrive”. Then, the winter fuel allowance cuts would have had a totally different complexion.

This is urgent. A new agenda for young people is a priority. An education and skills revolution for the AI generation is essential. But it will only happen with a new mindset: less moral panic and more listening, fewer lame TikTok memes and more substance, fewer quick fixes and a deeper commitment to the next generation.

“I’m proud to be British,” one 16-year-old told us in Birmingham, “but I don’t think Britain is proud of us.”

We haven’t lost this generation yet. But if mainstream politicians don’t start getting their act together, young people will look elsewhere for those who offer the hope of a better future.

How to communicate with young people

1. BE AUTHENTIC

Young people gravitate to personalities. Authentic voices that have a take on the world. They resist the “on message” scripted politician reading out the line to take, dancing around the issues, hiding from the difficult questions and failing to make an emotional connection. The young people we spoke to said:

“They just say what they think we want to hear. Not what they actually believe.”

“It always feels like they’re performing, not talking to us.”

“You can tell they’ve rehearsed everything. There’s no real emotion, no truth.”

“They use so many words and say absolutely nothing.”

“It doesn’t feel like they actually care about young people… It would be beneficial if they were more personable and more honest.”

“They don’t often do what they say, they lie and that’s how that stigma is brought about.”

“They should be more honest with policies to the people and not sugarcoat over their actual intentions.”

2. DON’T BE NEGATIVE

Young people, like the rest of the population, want a message of hope, to be able to see a brighter future.

“All they do is bash the other side. What are they actually for?”

“Politics feels like a never-ending fight, not a place for solutions.”

“It’s always blame, fear, outrage, nothing uplifting.”

“They’re always tearing people down, never building anything up.”

“They argue.”

“Too petty, too adversarial, attack each other too much, which limits cooperation significantly.”

“They insult the opposition without providing any of their own policies.”

3. CUT THE JARGON

Politician-speak goes down like a bag of cold sick. Young people want plain speaking and honest engagement.

“They talk like they’ve never had to pay rent or take a bus to work.”

“You can tell they’ve never sat in a classroom like ours or worried about paying for lunch.”

“They don’t get it. They talk about issues like they’ve never lived them.”

“They appear out of touch… trying to relate to the younger population doesn’t seem genuine.”

“Be more genuine, put things simply so that we actually understand what they’re trying to do.”

“They try to be relatable online, but it’s painful to watch.”

“Stop posting memes. Start posting meaning.”

“We don’t need you to go viral – we need you to be honest.”

“Just be real. We can tell when you’re faking it.”

4. GIVE US SOME VISION

People want policies and ideas that they can engage with. They want a sense of direction, a sense of what it’s all for.

“They talk about policies but not purpose.”

“I want to hear about the kind of future they believe in, not just what they’ll cut or fund.”

“It’s like they’re managing a system, not leading a movement.”

“They tell us what they’ll do, but not why it matters or what kind of world they want to build.”

“Too formal and boring, doesn’t engage with some people.”

Inside the Mind of a 16-Year-old by Shuab Gamote and Peter Hyman is published this week.

Shuab Gamote is a researcher and writer whose work explores how young people understand politics, identity and belonging in a rapidly changing world

Peter Hyman is a former advisor to Tony Blair and Keir Starmer and a former headteacher. He is author of the Substack, Changing the Story