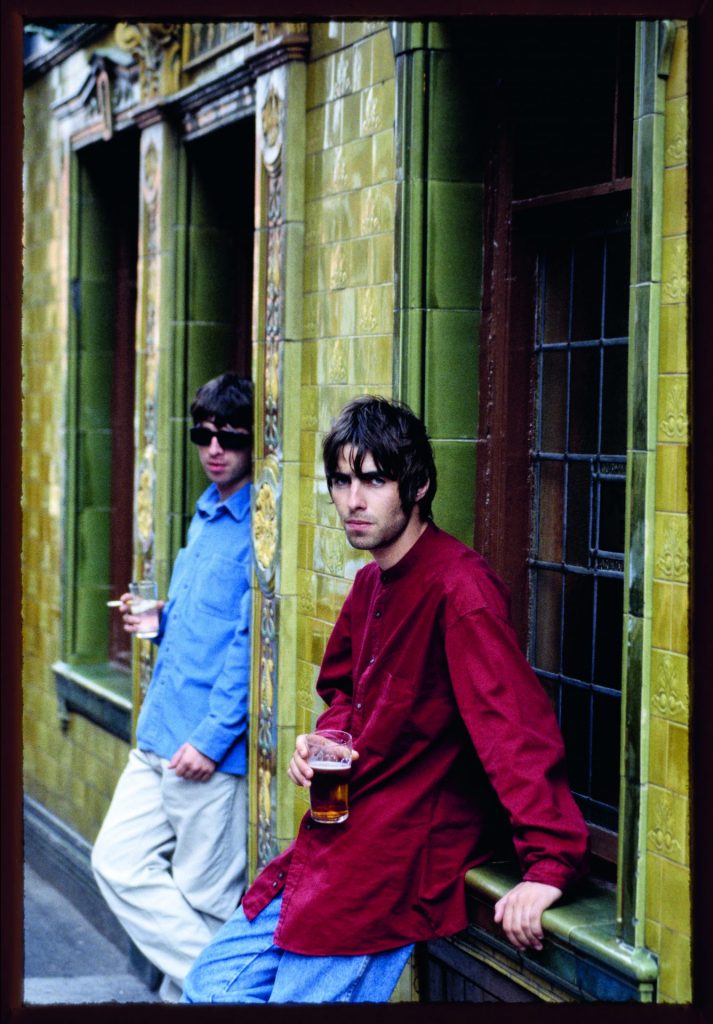

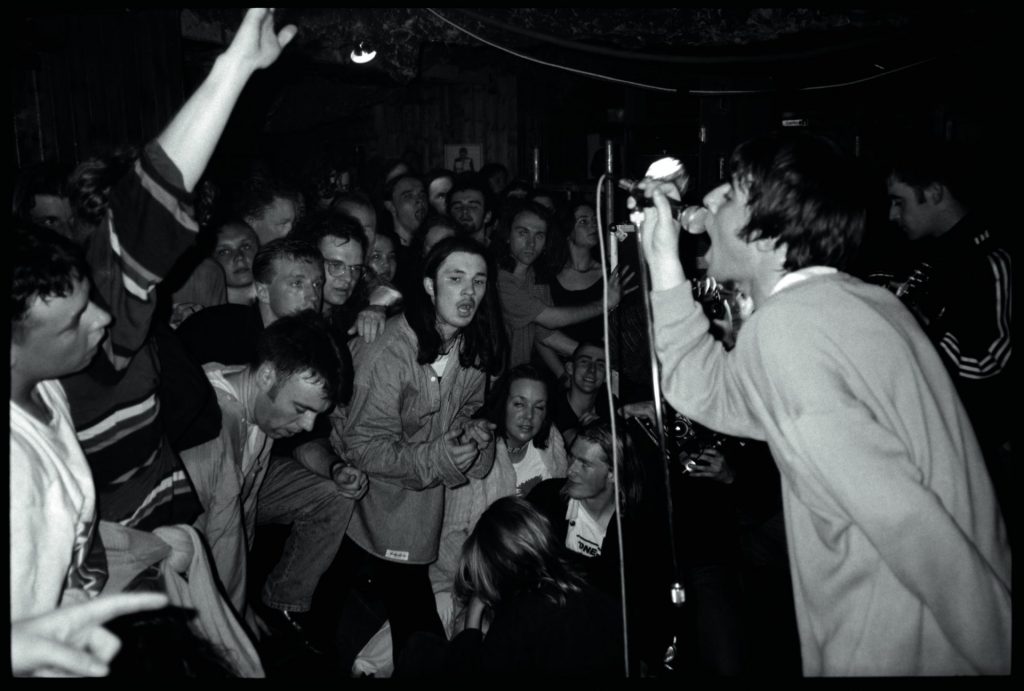

It’s April 1994 and although we don’t know it just yet, we’re in the presence of a rock ’n’ roll star. In Glasgow, Radio One-sponsored indie festival Sound City is into its third day. Almost all the bands playing there are staying at the same hotel. In the lobby bar, members of Pulp, The Charlatans and The Wonder Stuff shoot the breeze with their respective PRs. On the second floor, the doors of a crowded lift open and Britain’s next rock ’n’ roll star walks in. The conversation stops. With his Burnage pimp roll, you don’t know if the feeling you’re experiencing in the presence of Liam Gallagher is terror or excitement. In truth, you’re probably at the precise intersection of both.

Also in Glasgow for the week is a friend of mine, the guitarist and songwriter in an indie band, whose most recent album has been hailed by critics as a modern psychedelic masterpiece. But this past week, my friend has… how can I put it? He appears to have undergone a total personality transformation. Three years before the famous sketch on Harry Enfield & Chums in which Kevin and Perry fall under the same spell, it’s happening right in front of me. The afternoon he and I set eyes on each other – our first encounter in months – he saunters up to me as though he might be about to offer me out for a fight.

This once shy man – one of life’s perennial playground outsiders – wants to know if I’ve seen Oasis yet. Despite growing up in a completely different city, unmistakeable top-notes of Mancunian have entered his diction. He takes a slug from a bottle of Rolling Rock and sings the opening lines of Oasis’s newly-released debut single Supersonic, “I need to be myself,” he bellows, “I can’t be no one else”.

It’s easy to laugh, but my friend won’t be the last musician whose world will be turned upside down by Liam and Noel Gallagher. The disruptive energy of Oasis will leave almost nothing around them as it was before. Two days later, just as the festival is coming to an end, news filters through the hotel that Kurt Cobain’s body has been discovered in his conservatory. A somewhat bloody line is drawn beneath one era so that another can properly begin.

At times, I’m not sure how much we’ve moved on. The Kangol bucket hat favoured by Liam never fell out of favour with a certain sort of young male. Ditto the zip-up Adidas top. Millennials and Gen Z-ers are as word-perfect on Wonderwall as their parents. Last month, an entire episode of Britain’s longest-running sitcom Not Going Out revolved around its protagonist’s attempts to get tickets for their upcoming Wembley Stadium shows. You’ll probably remember that last August, an estimated 14 million people attempted to buy tickets.

Back in 1993, aged 23, I was working for Melody Maker. I should have been savvy enough to spot that British music was about to undergo a paradigm shift, that it was adopting a certain sort of swagger whose reach would spread into other branches of popular culture. But Liam Gallagher represented something I thought I’d forgotten. Suddenly it was all coming back to me. Yep. I remembered these people.

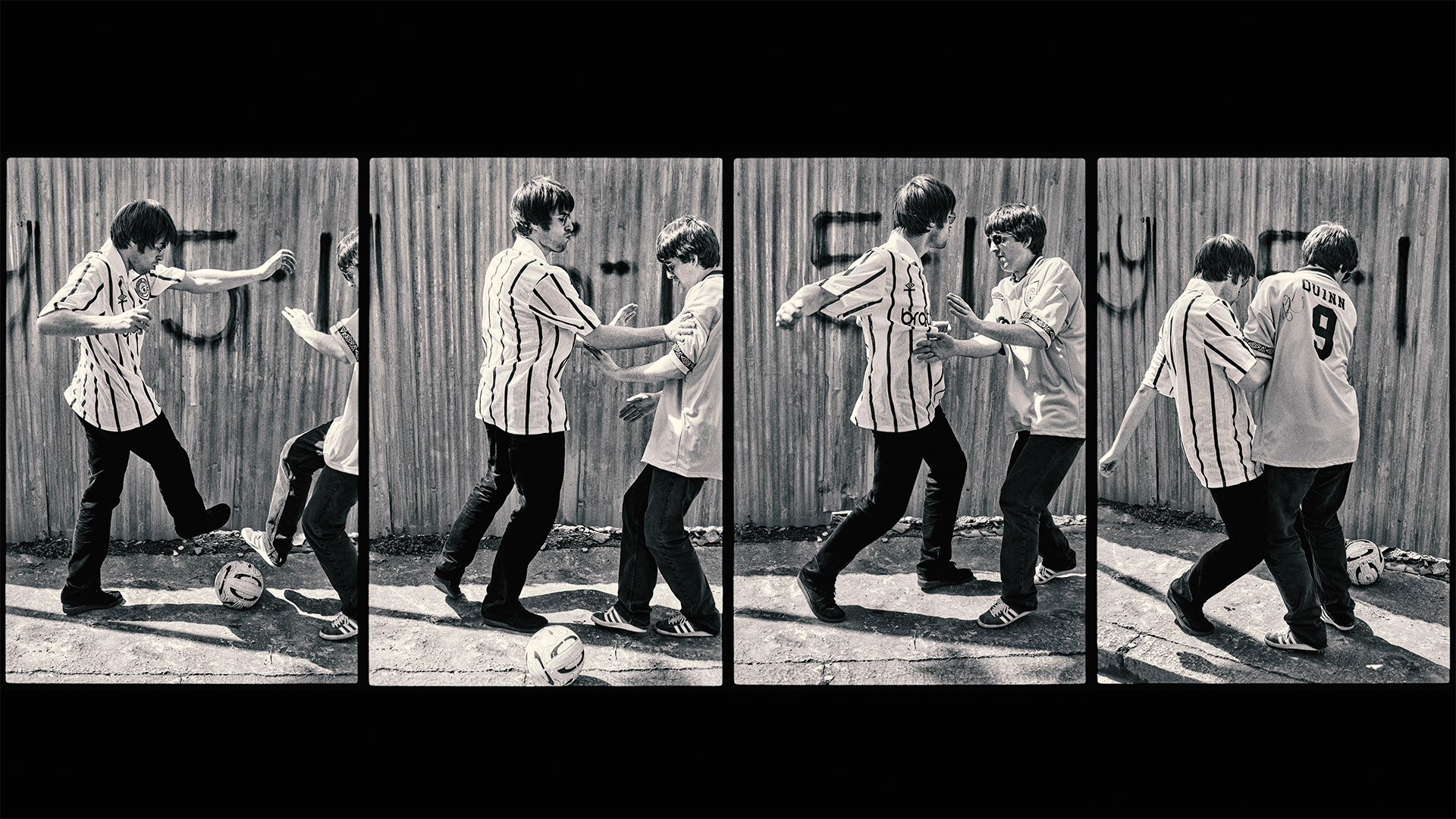

Six or seven years previously, they wore pastel-pink Pringle v-necks and Diadora Borg Elites. They called themselves football casuals and indie kids like me would often have to leg it home the moment we alighted the bus at night because if one of them caught sight of us, they’d use some tenuous pretext upon which to pick a fight. How is it that this group – far from being the antithesis of indie music – might suddenly be its future?

Suggested Reading

Beyoncé, Karen O and getting past the male gaze

Over the summer of 1994, I’m finding it hard not to take this blurring of tribal lines personally. But with each new Oasis single, something strange starts to stir. The group’s third single Live Forever lands into the top 10. I hear the lines, “Lately did you ever feel the pain/In the morning rain/As it soaks you to the bone,” and feel what I can only describe as a holy shiver. Then a few seconds later, “Maybe you’re the same as me/We’ll see things they never see.” These aren’t just great lines – they’re a dog whistle to everyone who, to quote another early Oasis classic (Columbia) “can’t tell you the way I feel.”

In fact, a lot of early Oasis songs seem to happen in the space between feeling a certain way and being able to put it into words. On Supersonic, it’s the line: “You need to find a way for what you wanna say,” On Acquiesce – not just their greatest B-side, but surely one of their very greatest songs – Liam sings, “I hope that I can say the things I wish I’d said/To sing my soul to sleep and take me back to bed/Who wants to be alone when we can feel alive instead?” And you’re left wondering why it is that three lines in a song can simultaneously sound so life-affirming and devastating.

An answer of sorts can be found in Ian Leslie’s new Beatles book John and Paul – A Love Story In Songs. In it, Leslie writes: “The songs [Lennon and McCartney] wrote and sang together were not ‘about’ their feelings – they were their feelings.” It’s a statement that constitutes a perfect fit for Oasis’s most affecting songs. Leslie also talks about John and Paul’s early creativity as a sort of trauma response to the recent loss of their mothers; a space into which feelings could be decanted and turned into music.

In his own memoir Surrender, it’s clear that Bono – who was 15 when his mother died – has come to a similar understanding of U2’s early work. When I hear Oasis’s early music, I find it impossible to miss a comparable response to trauma, but what fascinates me is the ways in which it differs from the trauma weathered by U2 and The Beatles (surely no coincidence, by the way, that Noel has repeatedly cited these two groups as two of his all-time favourites).

Tommy Gallagher is a shadow that looms large in Oasis lore. According to the Gallagher boys’ mother Peggy, their father would beat them regularly. When the two older boys Noel and Paul developed a stammer, he would also try to beat that out of them too. Peggy also told a story in which she tried to leave with Liam one night and Tommy threatened to burn down the house while Paul and Noel were still in it. According to Paul, “he’d beat Noel up in the middle of the night” and “tip the bed over so Paul and Noel would end up with it on top of them.” Noel’s coping mechanism was to retreat into himself. “Noel was always very quiet,” recalled Peggy. “You never really knew what he was thinking.”

Children process trauma in different ways. It isn’t hard to picture the way Noel dealt with his – solitary bedroom afternoons learning Beatles and Smiths tunes which, over time, would embolden him into writing his own songs. The anger that seems to have been thumped out of Noel is startlingly audible in the pugilistic brio of Liam’s early vocals for Oasis. An Oasis song without Liam is far more apt to conjure images of a withdrawn child in the corner of the room where their parents are fighting than anyone might otherwise expect.

If Noel could have made it as a musician without Liam, would he have done so? Almost certainly. One of his many resentments towards Liam is that his younger brother never showed any interest in music before deciding to accept an invitation from local group The Rain to audition for the role of singer. And you can just imagine it, can’t you? Liam clocking the listing of Oasis Leisure Centre on a tour poster for Inspiral Carpets in the bedroom he once shared with Noel. There’s his big brother trying to graft his way to a better life, working as a roadie for the Inspirals. Because Liam is all about projection, he can’t write a decent song to save his life. Because Noel is all about introspection, he can write them; he’s just not a rock star.

In that moment, Liam’s apparent ability to put in absolutely no effort and still get incredible results means two things. First of all, it will turn their dynamic into something you might more commonly find in a sitcom. The foundational principles of most sit-coms – from Steptoe and Son and Only Fools and Horses through to Frasier and The Office are co-dependency and/or incarceration. Two or more people whose differences are superseded by the fact that they need each other.

And, at times, they’re the funniest sitcom in town. It’s Punch & Judy with guitars; Basil and Sybil on coke. An early NME interview – in which Noel and Liam bicker over a brawl initiated on a ferry crossing which led to everyone in the band apart from Noel being arrested – accrued such infamy that it would end up being a minor hit when indie label Fierce Panda released it as a single. Noel seems to have a bottomless source of magnificent lines to sum up his brother: “A man with a fork in a world of soup”; “He’s constantly going on about how much soul he’s got,” Noel said. “I assume Bob Marley had soul… I don’t see Bob Marley at the Rainbow [the scene of the famous Wailers concert in 1977] wailing about the colour of the napkins in his dressing room.”

And yet what would Oasis amount to without Liam? Thankfully, it’s not something you have to imagine, because so many of the group’s most affecting early B-sides feature Noel on vocals, and they’re deeply melancholy affairs: Half The World Away, Sad Song and Talk Tonight are all cases in point. Whatever the logo on the front of your Don’t Look Back In Anger CD single might have you believe, an Oasis song without Liam is really just a Noel Gallagher song.

And with Liam? Wouldn’t you have wanted to be in the room the first time it happened? To have witnessed the eureka moment? The big bang without which Oasis would almost certainly have not happened? If, as Caitlin Moran wrote, anger is just fear brought to the boil, the change that underwent so many of Noel’s songs when Liam sang them was despair brought to the boil. And the good fortune enjoyed by Oasis once they came to the attention of Alan McGee is that they alighted on a sound which turbocharged what was already there – the more-is-more, needle-in-the-red opacity of Owen Morris’s production of Definitely Maybe was simply not how things were done. But on an album of songs that either couldn’t or wouldn’t articulate their feelings, it was perfect.

In the end, it didn’t matter that men like me were circumspect around Oasis. Because Oasis weren’t really aiming their songs at men like me. In August 1995 as Blur pipped Oasis to number one with Country House, they celebrated their pyrrhic victory with a valedictory tour of seaside towns. At Eastbourne, I was one of a bunch of writers who had gone to watch Blur play a Saturday night set at Floral Hall. In the hotel bar that night, early copies of the following morning’s Observer were circulated in which Noel had declared, “I hate that Alex and Damon. I hope they catch Aids and die.”

For Blur, it might have been a bit of fun. But I think that in that moment, we realised that it was full-on class war. With another three decades’ hindsight, I can now see this was also the beginning of that most pernicious of modern phenomena – a culture war. It isn’t hard to imagine the 23 year-old Dominic Cummings on the sidelines, taking notes.

For a moment, it felt like it had peaked for Oasis. Blur’s fourth album The Great Escape came out to positive reviews while Oasis’s (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? came out to lukewarm ones. The music press did what it so often did around this time and privileged the conceptual sophistication of one record while penalising what they saw as the derivative qualities of another. Speaking to the author Daniel Rachel in 2019, Noel recalled, “Nobody had heard Don’t Look Back In Anger by this point, or Wonderwall. Morning Glory was about to change the world, I knew it was coming.”

In the end, none of the reviews mattered. A common misconception, often propagated by music papers like the one where I worked, is that our music taste is a series of choices that we make, when it’s surely more accurate to say that the songs we love in some way tell us something about how we feel. In other words, we don’t find our soundtrack; it finds us. Perhaps this is especially true of men, or at least a certain sort of man who struggles to, well… tell you the way he feels. The proof is what happened next.

And so to Wonderwall. Writing in The Spectator last year, their pop critic Marcus Berkmann complained that Oasis’s most popular song (it currently stands at 2.4 billion streams, as many as the remainder of the top five combined) “doesn’t go anywhere, it just is, repeating itself over and over again until every cell in your body is shouting ‘Enough!’” But, of course, it doesn’t matter what Markus Berkmann thinks any more than it matters what I think. Neither do we need concern ourselves with the fact that some of the greatest songs ever – from Sidney Bechet’s Basement Blues to Kylie’s Can’t Get You Out of My Head – repeat themselves “over and over again”.

Even now, if you walk into a pub and that song comes on, you’re guaranteed to hear a bunch of men (and it’s always men) singing along to the lines, “There are many things that I would like to say to you/But I don’t know how”. The case on Wonderwall closed a long time ago. And every time someone like Berkmann or the late philosopher Roger Scruton – who in 1997 took against the lack of “original thought” and “musical talent” from their music – makes these pronouncements, they place another implement on the Buckaroo donkey of working-class hatred of “elites” which resulted in Brexit (I’m not entirely joking here). In any case, pre-emptive ripostes to this sort of sophistry don’t come much better than the one issued by Oasis in 1995 when they covered Slade’s Cum On Feel The Noize: “So you think my singing’s out of time/Well it makes me money.”

Oasis couldn’t have been anything other than massive precisely because they articulated a personal manifesto that several million people in this country shared. This isn’t speculation. Oasis told their audience who they were on the very first song of Definitely Maybe. Rock ’n’ Roll Star isn’t just about being a rock n’ roll star. It’s about the working-class dream of escape from the nine to five. Doesn’t matter how you do it. It can be winning the pools, becoming a footballer or pulling off a heist. You’re Viv Nicholson. You’re George Best. You’re Ronnie Biggs. These are all different iterations of the same fantasy. That one day you’ll buy a castle, like David Essex in Stardust, pull up the drawbridge and move far away from the council estate where you were raised.

It’s why, as soon as the money came in, Noel and Liam offered to buy their mum any house she wanted (she elected to stay where she was). This isn’t a betrayal of your roots. If you’re lucky, it’s the germination of them. It’s why Noel sings “Please don’t put your life in the hands of a rock ’n’ roll band/Who’ll throw it all away”.

It’s the belief that money will make you happy. Because, if you never had any, why would you think otherwise? It’s why Oasis didn’t have a Beetlebum, a Song 2 or a Tender in the pot by the time they got to the cokey grandeur of Be Here Now. Because, in this dream, escape is the objective, not personal growth (plenty of time to address once you’re lounging by the pool). And far from resenting Oasis for it, it seems to me that their fans expected nothing less.

Suggested Reading

Kneecap have their day in court

I would argue that it’s a middle-class category error – and quite a condescending one at that – to presume that there can only be one working-class dream. Sure, there’s the noble one, in which you make it and you bring as many people as possible with you. You do lots of charitable deeds and put something back into the community. Perhaps that’s what you do if you believe in “for the many and not the few”, but lest we forget, Noel Gallagher’s disdain for the originator of that slogan surpassed even the antipathy he feels for his brother: “Fuck Jeremy Corbyn,” he memorably declaimed in 2017. “He’s a Communist.”

I think that, in his bones, Noel deplores the idea that life is a level playing field. And I suspect he has done ever since he had to endure the indignity of sticking his tail between his legs and asking his charismatic, workshy, ungracious brother if he could join his band – because in spite of all his hard work, Noel didn’t have what it took to do this alone.

It might be that this moment of ignominy is also what informs Noel’s contempt towards pop stars – from Beyoncé to his own brother – who can’t write songs without help from other songwriters. That’s also worth remembering in view of the months leading up to Noel’s departure from the group in 2009, when Liam stopped attending his own soundchecks; in view of Liam’s failure to record a single vocal during eight weeks of sessions at Abbey Road for Oasis’s final album.

And herein lies the bitter irony of the interdependence that birthed Oasis. Having grown up in the same building as an angry man, Noel discovered that his plaintive pretty songs only go supernova when his brother brings his own aggy elemental energy to bear on them. Separately they’re ok. But together, they’re one of the greatest singer-songwriters of their generation. I’m just not sure Noel is ever going to be ready to hear that.

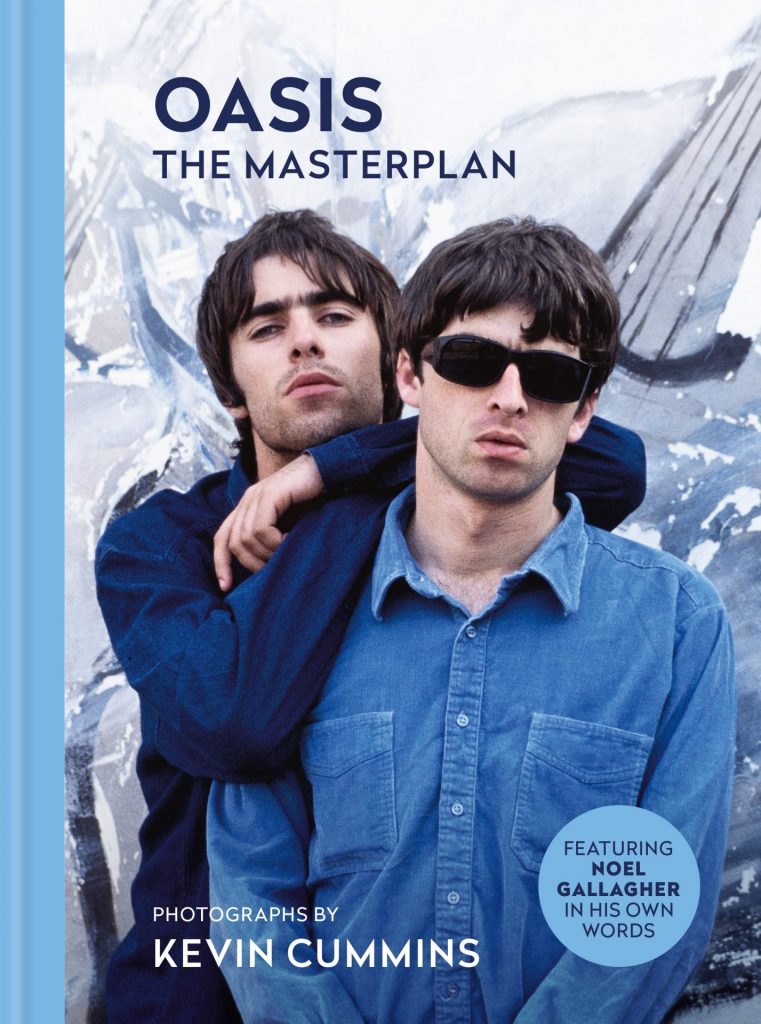

Oasis: The Masterplan by Kevin Cummins is out now, published by Cassell