With Keir Starmer’s future in the balance, the only certainty is that in Munich this weekend, Britain must stand up and show leadership. The annual Bavarian jamboree for western security elites comes at a critical moment: US forces are massed against Iran, Nato is creaking from the after-effects of the Greenland crisis, and Europe has been left almost alone to support Ukraine as Vladimir Putin’s rockets massacre civilians.

Amid the turmoil, the world needs Britain to throw its weight behind containing the Russian threat, stabilising the Middle East and shoring up the western alliance. Because it is very clearly in peril.

Mark Carney’s speech at Davos spelled out the problem: the rules-based international system is falling apart and the security architecture – indeed the basic assumptions – of most democratic countries were based on its unquestioned permanence. The Canadian prime minister pleaded with mid-sized democratic countries to stick together and form a distinct bargaining group to counteract US isolationism, Russian aggression and the inexorable rise of Chinese power.

At Munich we will begin to find out whether that can happen. But even those steeped in the language and literature of international relations are struggling to get their heads around the enormity of the problem.

Suggested Reading

Welcome to the even nastier party

The experience of great power competition is beyond the living memory of most people. Likewise the experience of US isolationism. We are conditioned to believe that there is international law, to be enforced by international courts and shaped by universal principles. We knew, of course, that these laws were broken, the courts ignored and the principles flouted – but they were at least a yardstick.

Now the central assumptions of post-second world war geopolitics have to be abandoned. We are, for the moment, engulfed in a four-way strategic “game” in which Britain’s choices will be critical to the outcome.

China’s aim in this new great game is to become the strongest country on earth by 2049, surpassing the west by creating a range of new hi-tech industrial sectors that barely exist today. But it does not want to become what America was in the mid-20th century – the hegemonic power shaping all others to its will.

It is a plausible objective, and if it fails it will be because of internal social unrest, economic stagnation and regional rivalry, not the designs of others.

Russia’s aim is, by contrast, batshit crazy. Its rulers believe that a country with a GDP the size of Italy’s can wage an ethno-nationalist war of conquest in Ukraine, dominate the Arctic, divide Europe and shatter Nato. But if Putin’s theory of victory is irrational, his theory of defeat is chilling. “What is the point of the world,” he mused in 2018, “without Russia in it?”

Under Donald Trump, the US’s strategic goal is to dominate the Americas, contain China and force Europe into a kind of economic vassal status, whereby we fund America’s debts but are not allowed to run a trade surplus with the US. This is a hugely fragile plan – prone to the risks of foreign states abandoning the dollar as the global reserve currency and to internal democratic collapse.

Europe, insofar as it has a grand strategy at all, wants what Ursula von der Leyen calls “open strategic autonomy”: a deeper market, rapid rearmament, removing the fiscal brakes built into the Maastricht and Lisbon treaties. At the same time it must resist Trump’s explicit plan to undermine liberal democracy in Europe and replace it with divisive, authoritarian ethno-nationalisms.

And the UK? Its politicians have been living in a dreamworld since Brexit. First, Boris Johnson declared we were “Global Britain” – determined to wage a one-country fight to end trade protectionism. That was in 2020. Six years later we are stuck in the middle of a transatlantic trade war, desperately trying to hold together the Nato alliance on which we have based our entire national security strategy.

If you survey this four-way competition, the dynamics have stark consequences for the UK. It does not matter whether Trump and Putin have done a secret deal to betray Ukraine and carve up the Arctic: objectively their stated strategies share the aim of dividing and de-liberalising Europe.

In Britain, no matter how strongly we are attached to Ernest Bevin’s original aim with Nato – to keep America invested in the defence of Europe against Russia – we must recognise that it is in danger.

So the British prime minister must go to Munich not just with warm words, or an emollient tone towards both sides of the Atlantic, but with a clear commitment to collective European security and rearmament.

British politicians like to think that, along with France, fellow nuclear-armed member of the P5 permanent members of the UN security council, we are the leading security power in Europe. But Germany, Poland and the Nordic and Baltic states are now outspending us as a percentage of GDP. With that, diplomatic leadership and soft power is passing to Berlin.

Suggested Reading

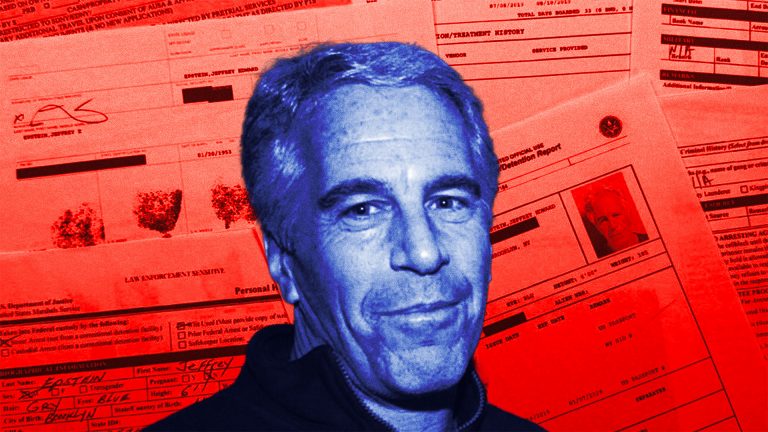

Techno-financial fascism is at the depraved heart of the Epstein files

The fear stalking the corridors of the Bayerische Hof this weekend is that Trump will suddenly pull either US forces or US commanders from Europe. And though Europe will soon be strong enough in terms of land, sea and air power to defend itself against Russian attack, it lacks the so-called “strategic enablers” to deter Russia on its own.

These range from spy satellites to long-range missiles, early-warning radars and the specific mix of aircraft and missiles needed to take out enemy air defences. That’s why Nato general secretary Mark Rutte told the European Parliament last month that they were deluded to believe Europe can defend itself alone.

But it must, within a very few years, put itself into the position where it can do so. And that’s a delicate task as well as an expensive one: the fine art of the next 10 years will be for Europeans to assert their agency and autonomy without causing a pre-emptive US withdrawal.

Watching the Democrat presidential hopefuls this week, I am confident Trump and JD Vance can be driven from the White House in 2028. Any one of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Jon Ossoff or Gavin Newsom could create a centre-left populist surge that defeats MAGA, provided democracy itself holds. After that, even if the US wants to remain isolationist and Pacific-focused, the malevolence will be gone.

But I am not confident that peace in Europe can survive until January 20, 2029, when Trump must leave office. That is why Britain must do two things explicitly at Munich: commit to a strong, unified and deepened Europe; and redouble efforts to create and join the multilateral lending institutions that can fund rapid rearmament.

Above all, we must commit to the defence of liberal democracy in Europe: its destruction is the shared aim of Trump and Putin. Its survival and flourishing must become our own.