Shortly after 2am on January 3, with Caracas’s air defences in flames and its citizens livestreaming the mayhem via social media, US special forces burst through the doors of a government compound and seized the Venezuelan president, Nicolas Maduro.

Ninety minutes later he was in a helicopter en route to the USS Iwo Jima. Within 24 hours he was in a Brooklyn detention centre, facing charges of cocaine smuggling and “narco-terrorism”. It was an event of vast geopolitical significance.

The USA has intervened to topple governments in the Americas several times, most recently in Grenada in 1983 and Panama in 1989. But this feels different.

It is a blatant exercise of American hard power, with Trump pledging to “run the place” via the deputy president of Venezuela, Delcy Rodriguez. Trump explicitly tied the coup to the goal of regaining ownership and control of Venezuela’s oil reserves and infrastructure.

As with all of Trump’s spectaculars, the aftermath is likely to be messy, improvisational, and owe more to showbiz than to statecraft. Rodriguez is a Rosa Kleb-type figure within Venezuelan state socialism, who once appeared at Madrid airport with 12 suitcases of gold bars to disburse – allegedly – to Spanish politicians, even though she is banned from entering Spain.

With the democratic opposition sidelined, Trump looks set to run Venezuela through a classic comprador bourgeoisie – only now with the supposed anti-imperialists acting as the compradors (collaborators).

But this was, whatever the outcome, a world-changing event.

First, it signals that Trump wasn’t kidding when, in the National Security Strategy published in December, he announced a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine. The NSS made clear that, from now on, the peoples of the Americas will be required not only to acknowledge the US as the decisive power over them, but to expel the Chinese and European capital that has entered their markets during the period of globalisation.

“We want,” said the NSS, “other nations to see us as their partner of first choice, and we will (through various means) discourage their collaboration with others.” The Caracas raid was an example of the means available.

Secondly, it heralds the likely demise of the one-party regime in Cuba, which has become wholly dependent on Venezuelan oil. Some 32 Cuban soldiers were killed during the raid, having been installed as the Maduro regime’s most reliable military force. The timing, form and final destination of Cuba’s transition will, of course, be a matter for the Cuban people and their allies across the world, something that cannot be left in the hands of Trump and his oligarchic vultures.

Third, it raises the possibility that Trump’s fantasy of controlling Greenland could be achieved by the same kind of coup de main – only this time against Denmark and the European Union.

Fourth, and most ominously, it opens the door to a strategic deal with Putin in which the US gets Venezuela and Moscow gets part of Ukraine and a free hand in Europe. Fiona Hill, Trump’s former adviser, testified in 2019 that, during negotiations with the Kremlin the Russians were “signalling very strongly that they wanted to somehow make some very strange swap arrangement between Venezuela and Ukraine… You know, ‘you have your Monroe doctrine. You want us out of your backyard’.”

Though no such offer is on the table during the current negotiations, it is clearly present in the minds of the most isolationist, and most pro-fascist elements of the Trump administration, and will require deft diplomatic work by European leaders to stop it crystallising.

Finally, the Caracas raid signals a change of gear in the process of global fragmentation. Until now the US has acted as a check on that process – funding Ukraine’s resistance, muscle-flexing around Taiwan and maintaining its leadership role in Nato, despite threats to reduce its commitment.

If we are unlucky, the seizure of Maduro signals that Trump simply wants to play the great game of hard power and arbitrary force, sidelining Europe and India in a three-way battle for power, resources and influence between Washington, Beijing and Moscow.

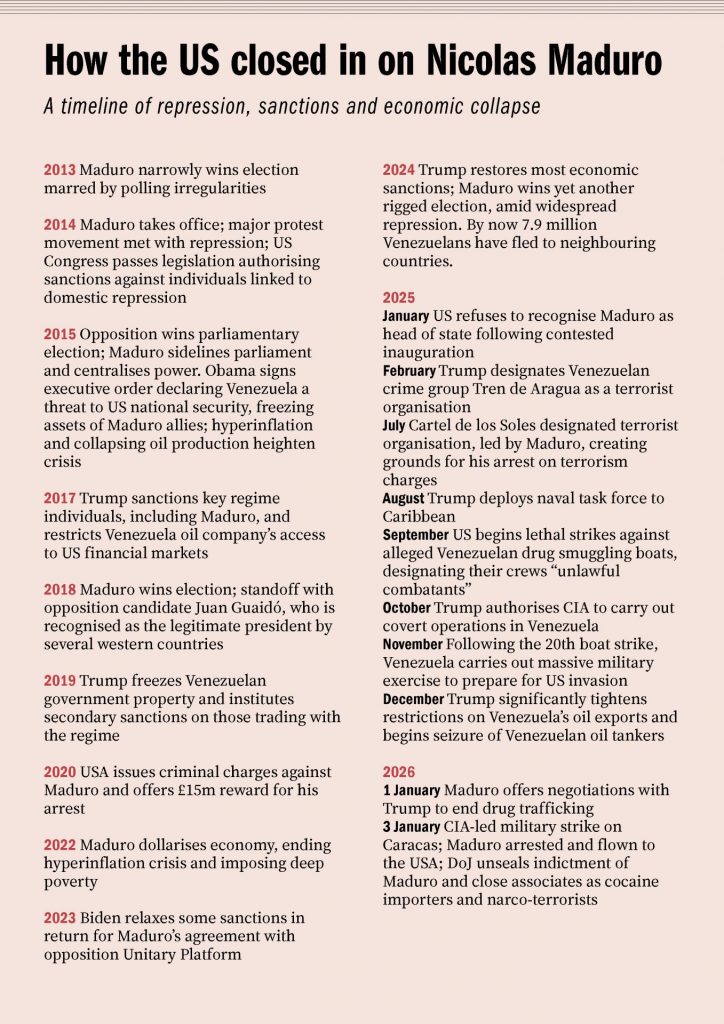

The legal case against Maduro was not summoned out of the Maga imagination. After he greeted widespread protests against his disputed election victory in 2013-14 with harsh repression, the US Congress imposed sanctions on key members of his administration.

It was Obama who declared the Maduro regime a threat to US national security, and Trump in his first term who imposed severe sanctions both on the state, its leaders and its national oil company, eventually laying criminal charges against Maduro in 2020.

Though Biden relaxed the sanctions, in an attempt to persuade Maduro to compromise with the opposition, the criminal charges were never rescinded. And when Trump regained the White House, appointing Marco Rubio as secretary of state, the choreography leading to last Saturday’s strike began in earnest.

The US added “terrorism” to the charge sheet, built its legal case, started blowing alleged drug smuggling boats out of the waters of the Caribbean, amassed a significant flotilla and then struck.

But this is not primarily a law enforcement operation; nor is it a straight, Bush-era exercise in nation building. For now, Rodriguez will rule Venezuela, retaining much of the “Bolivarian” state apparatus and the paramilitary forces used to put down repeated democratic protest movements – actions for which she remains sanctioned by the EU and banned from travelling there.

Spain, Mexico, Uruguay, Brazil, Colombia and Chile have denounced the move and expressed concern over Trump’s stated desire to get hold of the country’s oil reserves. But in the end, this is not even about oil. It is a step towards securing the Americas as a hermetic sphere of influence, export market and source of raw materials for the US, in the interests of the US, and not in the interests of the 710 million non-US citizens who live there.

It is, in short, an act of modern imperialism, and is designed simultaneously to counter the interests of two rival imperialisms: Russia and China. Though Trump could barely keep himself awake at moments during Rubio’s press conference on the raid, it looks like both a crime and an act of genius.

Suggested Reading

The beginning of the end for Donald Trump?

Between 2007 and 2016 China advanced around $60bn in loans to prop up the regimes of Maduro and his predecessor Hugo Chávez. The loans were secured against Venezuela’s heavy crude oil deposits, and repaid in oil, not cash. Though Caracas supplies only around 5% of China’s oil needs, it is an important source of heavy crude, and a vital alternative to the Middle East when it comes to diversifying China’s supply lines.

After Venezuela’s oil output collapsed – from 2.6m barrels a day to just 330,000 between 2016 and 2020 – the Chinese loans dried up, and Beijing has spent much of the present decade trying to get its money back.

In military terms Venezuela is primarily Russia’s client rather than China’s, but Beijing supplied powerful anti-aircraft radar, which turned out to be easily jammable by the US electronic warfare planes deployed last week, rendering the Russian made anti-aircraft missiles useless.

What does Trump gain by securing even partial control over Venezuelan oil? First, he removes a vital source of supply from China’s grasp. Second, he diversifies the US’s own supply of heavy crude, which has become dependent on Canada. Third, he gains a lever over the global price of oil – where Russia becomes economically vulnerable to price cuts, should supply suddenly increase.

But if he can reorient the Venezuelan oligarchy in favour of the US, he gains a lot more than that. China is engaged in a long-term operation to monopolise the supply and processing of critical minerals across the planet. And in the south of Venezuela there are ample supplies of three such minerals: tantalum, antimony and cobalt.

Over the past decade, China has established control over these mining operations, often in collaboration with local paramilitary groups and corrupt regional politicians. Iran has also built drone manufacturing sites in Venezuela.

So geopolitically this move – should it work – is a slam dunk for the US. It gives the US access to oil, rare earths, a new oil-rich client state for its military hardware and its exports and checkmates China, Russia and Iran in a region where they have invested decades of soft power and hard cash.

Suggested Reading

Trump’s deadly game of risk in Venezuela

The British reaction to the Caracas raid was co-ordinated with the main European powers and intended to be muted and non-committal. While opposition parties have raged about this, they are wrong to do so, because the security of this country is in great peril, and depends on preventing any impulsive moves by Trump over Greenland, Ukraine, tariffs or Nato commitments.

The strategic problem for European states is that they have been abandoned by their supposedly staunchest ally. Whether Trump turns out to be an unpleasant blip is immaterial to the fact that the US is now an unreliable ally.

That means Europe must either cohere or die: it must fight its way to the status of an equal player in the global power game, or it will become the chessboard.

And the problem for the UK, as readers of this newspaper understand, is that we walked away from Europe and contributed to its breakup; Brexit has made us insecure in ways we could not anticipate in the pre-Covid, pre-Trump, pre-Ukraine war world.

Though the UK’s nuclear deterrent is formally independent, Trump has the means to pull the plug through access to maintenance, warhead technologies and missiles.

So rather than grandstanding over the fate of Maduro, the British government must act on three fronts.

First, rejoin the Customs Union without delay. Second, rearm in earnest. The bond markets understand what the OBR will not – that investment creates growth and investment in defence, energy security and dual use technologies is our path to the future.

To my left wing and pacifist friends who are hostile to rearmament, I simply point to the flaming wrecks of Russian SAM missiles in Caracas and ask: can you now see the point of having an armed force capable of defending the country?

Third, it is time for an active European geostrategy. The UK’s National Security Strategy, published in July, is an admirably frank document, stating that we will “come out of our defensive crouch”, take risks and sometimes take actions that are in our interest but do not accord with our values. The Starmer administration now needs to do these things.

We can create, not just with the EU but with a coalition of democracies such as Canada, Switzerland and Japan, something that survives the ending of the rules based order; something with the moral authority to ask – as the greatest generation did in the 1940s – “what does the world look like when we win?”