After various painful contortions, RedBird Capital finally withdrew its bid for the Telegraph group, seen off by the UK’s determination that it did not want “foreigners” controlling what was portrayed as a great British institution. There is now only one bidder. DMGT, the publisher of the Daily Mail, has been given exclusive rights to pursue the target it has long had in its sights.

This may be good news for those who want an even stronger right wing press in the UK but no one else should applaud this outcome. The takeover is by a privately owned company controlled by Lord Rothermere that’s happy to air and promote authoritarian views. The idea that this is preferable to bringing in an overseas investor is a triumph for vested interests and narrow-mindedness.

Mixed messages seem to be endemic in this government but, given that overseas organisations are allowed to control huge amounts of the country’s infrastructure, often with dire results for the residents, the protectionism shown to the Telegraph reeks of hypocrisy.

Last week the government’s Baroness Twycross tried to justify the contradiction: “There is a difference between foreign investment in other parts of the UK economy, including utilities, and the free press that is a fundamental cornerstone of our democracy, and which we want to continue without foreign state interference.”

Really? The United Arab Emirates, which had been pivotal to the RedBird bid, has been actively enticed to pour its money into UK industry, particularly technology. It might now be feeling rather less warmly disposed towards a country that regards it as a potentially malign force when it comes to newspapers.

Hastily enacted legislation in May restricted state-owned investors from owning more than 15% of a UK newspaper group, following a knee-jerk total ban by the previous Tory government in response to the Telegraph’s predicament. But what, exactly, did they fear from such investment?

A “free press” is a glorious concept based on the freedom to write what you want, not what the government dictates. But newspapers have rarely managed to avoid bias and most are renowned for veering in a particular political direction. Readers know where they are coming from and, usually, what to expect. Given the rapidly changing shape of the media, with people drawing their information from numerous sources, predominantly online, the influence of traditional newspapers is much diminished.

Would the occasional good word about the delights of Abu Dhabi appal Telegraph readers? Might editorials extolling the virtues of more authoritarian regimes change their way of thinking? Probably not.

The Telegraph Media Group website insists: “We embrace many perspectives, backgrounds and viewpoints,” but left-leaning readers might struggle to find evidence of that. Readers of traditional newspapers expect a degree of predictability from their chosen reading. A foreign government thinking it might influence an important part of the UK by infiltrating one of its oldest newspaper groups would be destined not only for disappointment but a very poor return on its investment as anything too blatant would probably drive down circulation and revenue.

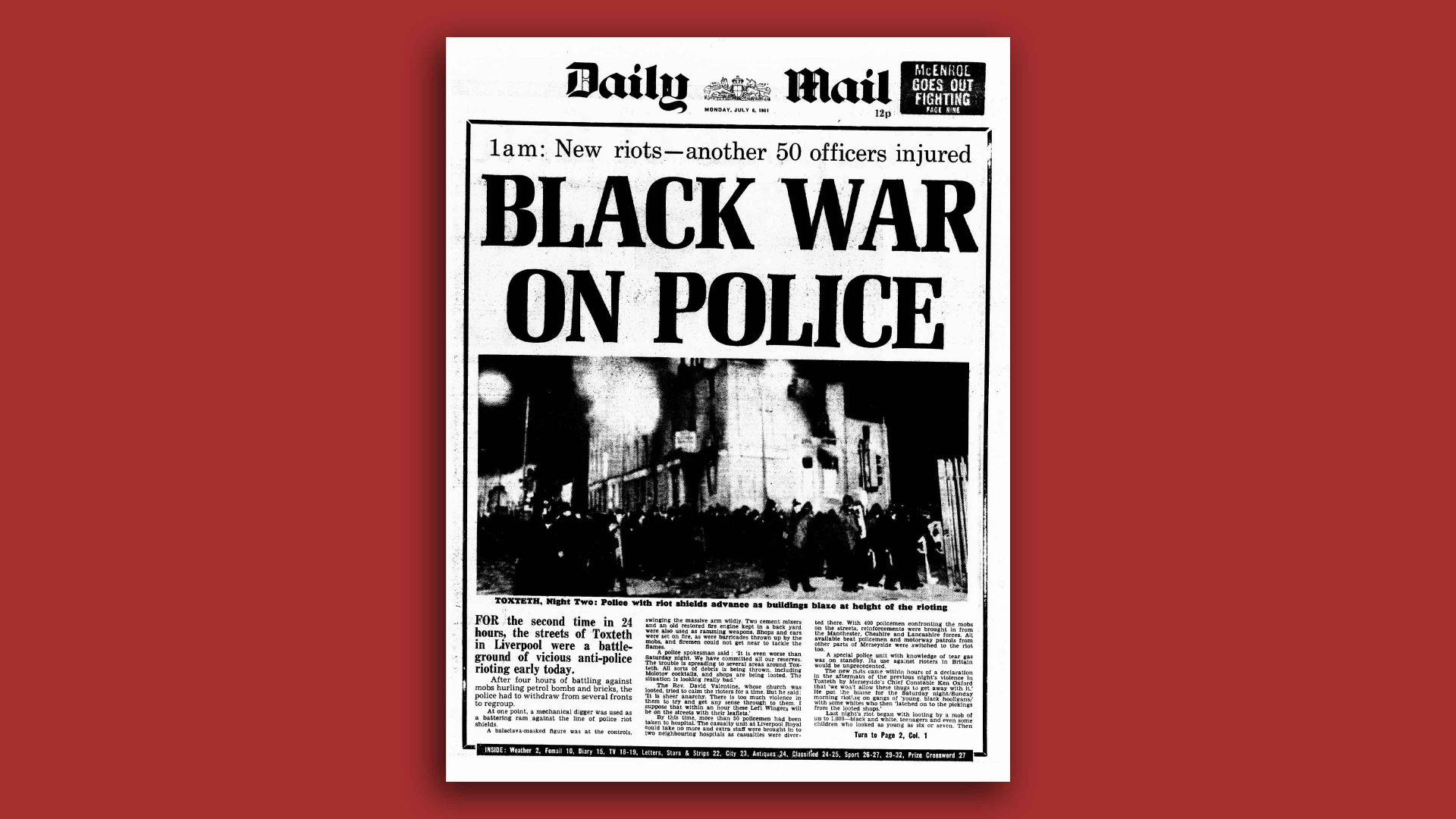

The Daily Mail and Telegraph share devotion to Brexit, the right wing and low taxes. They both despise “welfare scroungers” but campaign on behalf of pensioners, a core readership for the Telegraph. Combining them is an insult to the idea of media plurality and that should ensure that there is a prolonged hiatus while the government at least makes a pretence of having the deal investigated by the competition authorities. But the concerted hostility that has confronted outside bidders for one relatively small media business should ensure no others venture near.

The Telegraph’s website makes no mention of the ownership lacuna in which the group now languishes but it does pay tribute to its original proprietor, Colonel Arthur B Sleigh. Nursing a grudge against the then Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, he wanted to share it with as many people as possible.

He launched the Daily Telegraph and Courier to spread his views, but attacking the establishment then did not prove lucrative and his first edition was not a financial success. His ownership failed to survive beyond that, but the newspaper did, shortening its name and broadening its subject matter.

Since a different financial crisis stripped the Barclay family of its ownership of the titles in 2023, most readers will have been relatively unaware of the turmoil that has ensued as the paper kept on publishing, relishing the Epstein-related downfall of Peter Mandelson and the stamp duty-inspired defenestration of Angela Rayner. Telegraph journalists have also been well placed to put their own perspective on potential proprietors and they certainly did not warm to the idea of working for RedBird. Colonel Sleigh would surely have been impressed by their tenacity.

The chairman of RedBird Capital, the private equity firm that was leading the Telegraph bid, has strong links to China. The Telegraph found a way to link this to the recent revelations about Chinese spies in Westminster and thus dealt a lethal blow to any potential deal.

If the UAE had been considered unsuitable to hold more than a minimal stake in a British newspaper business, the prospect of China being involved at all was unconscionable. Seeing off RedBird was a clear victory for Chris Evans, the Telegraph editor, and his team but they and the government now have to ask themselves what foreign investors they would countenance in a UK newspaper business, particularly given that the “paper” bit is vanishing.

There was barely a ripple of excitement when, 10 years ago, the venerable Financial Times was sold to the Japanese company, Nikkei. Rupert Murdoch was Australian and then American but that was never used as an objection to him being in charge of a raft of British media, including the Sun and the Times. And the Telegraph was owned by the Canadian-born Conrad Black until his empire unravelled, eventually landing him in jail.

The previous owners of the Telegraph, the Barclay family, chose to divide their time between a fortress in the Channel Islands and luxury flats in Monaco but that did not appear to cause successive British governments undue concern. Yet now, “open for business” Britain has become positively xenophobic about this one sector of the economy.

In the age of Meta and AI, TikTok and YouTube, concerns about newspaper ownership seem not only outdated but potentially damaging to the government’s broader ambitions.

Patience Wheatcroft edited the Sunday Telegraph, 2006-7