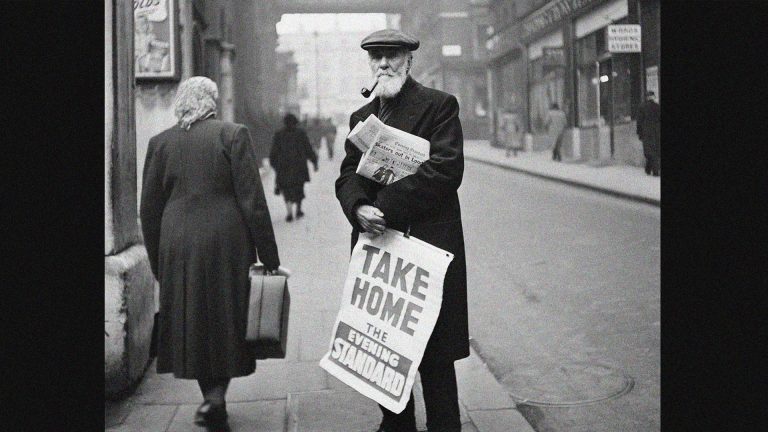

Long, long ago in the world of newspapers in which typewriters had only recently been replaced by what was warily known as “the new technology”, a distinction between news and comment still existed. Its edges were fraying, but there was an understanding that readers should be given the news untainted by the personal opinions of journalists.

Today such distinctions seem as antiquated as the John Bull printing press. Now that armchair pundits and bar-room bigots can send their views ricocheting around the world in nanoseconds, the established media seems to have decided that simply reporting the facts is not enough. If news is its business, then the media increasingly wants to be making it.

Occasionally, events occur that are so dreadful that the media has to accept it is only the messenger, and recent days have certainly delivered those, with Israel’s meticulously mounted attack on Iran and the devastating Indian plane crash. It did not take long, though, before the thoughts of various experts and commentators were being so melded with the known facts as to become a seamless whole.

Last week produced a particularly graphic example of the current approach to the concept of news. Ed Miliband, the UK energy minister, was being interviewed ahead of Rachel Reeves’s spending review, but after the chancellor had made clear that the winter fuel allowance would be restored to some pensioners this year. Miliband can speak passionately and persuasively about energy issues. But that did not interest the interviewer. He simply wanted to get Miliband to apologise for the winter fuel debacle.

Miliband would not offer the fatuous apology that was requested – many times. That gave the interviewer his “scoop” – Miliband refuses to apologise! – which was then reported on that radio station for the rest of the day. This manufacturing of news did not stop there. Miliband’s refusal to say sorry was soon being dutifully reported by other outlets. The story spread.

In a crowded media landscape, outlets are increasingly conscious of the need to build their brand, and so are the individuals who work for them. Where once ambitious journalists yearned to reach the status of columnist, today the aspiration is as likely to be to win enough of a following, or sufficient notoriety, to have a lucrative podcast. To be an influencer is a serious career option, and it seems a growing cohort of journalists have similar leanings rather than a strong belief in impartiality and straight reporting.

Suggested Reading

The slow death of local news

Impartiality does not mean impassivity. Interviewers should press their case if they are in search of genuine information. The most obvious example is Jeremy Paxman’s famous 1997 set-to with Michael Howard, then home secretary, when he put the same question to Howard 12 times. But Paxman was trying to elicit a fact: whether it was true that Howard had tried to reverse a decision of the head of the prison service. This was information with value to the electorate.

In contrast, a feigned apology from a minister for something for which he had not been directly responsible would have been utterly meaningless, and yet its absence was deemed newsworthy.

In this new world fraught with tensions, there is undoubtedly a desperate need for genuinely informed and insightful analysis, but that must surely come alongside clear reporting.

Establishing facts is not always easy, and sometimes not possible. It is clear that there will always be those prepared to fill the gaps, and the internet has provided them with a wonderful vehicle. Malign forces, such as those emanating from Russia that endeavour to interfere with elections, have had a measure of success online. The risks they pose make it even more important to have media outlets that draw a distinct line between news reporting and comment.

As a public service broadcaster, the BBC would seem the obvious place to find that reliability and, although there are numerous allegations of bias against it, they come from so many diverse and sometimes diametrically opposed sides that they cancel each other out.

Nonetheless, the BBC does seem to have fallen victim to another growing trend – boasting. Listeners are told that a particular programme is “brilliant”; interviews are repeatedly trailed and then, afterwards, discussed and dissected with much mutual back-slapping. This is of little benefit to the audience, but may be geared towards awards, which, presumably, might pave the way to that lucrative podcast.