If an elderly man accidentally dropped some important papers, the polite reaction of the person standing next to him would surely be to scoop them up and return them. If the one losing his grip, in every sense, happened to be president of the United States, some might hesitate. But not Sir Keir Starmer: he quickly bent down, fumbled a little, but successfully returned the documents.

Inevitably, his critics revelled in an image they chose to interpret as the British prime minister grovelling at Trump’s feet. It cannot be the picture Starmer would choose as a memento of the G7 summit, or that he would have wanted on the front pages of newspapers just days before war broke out in the Middle East.

But what has perhaps been lost in the torrent of news is that those papers represented something more positive: a trade deal that was far from perfect, but is more advantageous than anything that others have achieved.

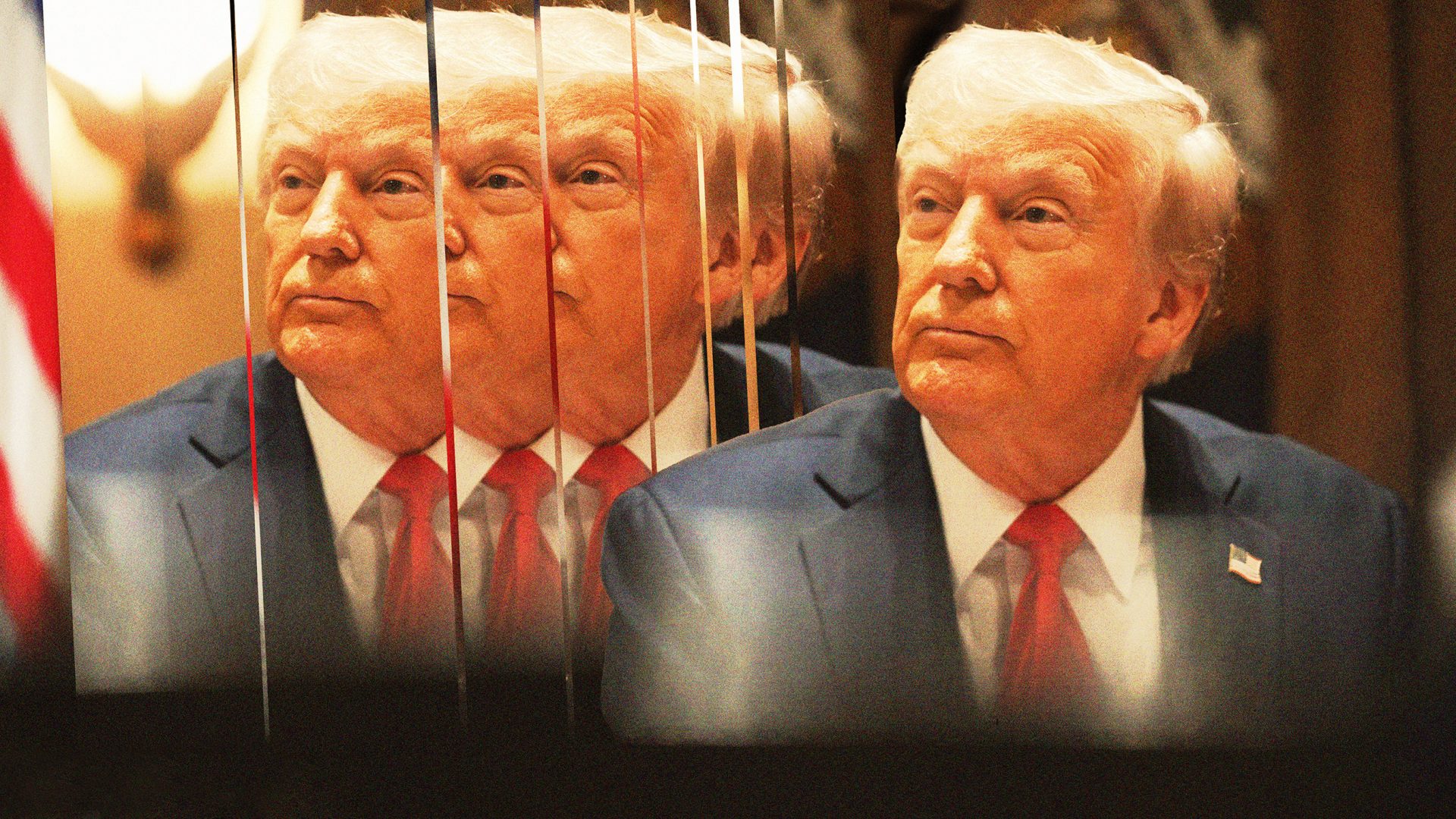

Donald Trump explained his relative generosity to the UK as being “because I like you”, but he is as fickle as any fashionista with his favours.

For Starmer, the former director of public prosecutions now coming up to his first anniversary as PM, a previous career dealing with criminals must represent relative sanity compared with the madness he now encounters on the world stage, where he must make sense of, or at least find a way of coping with, a world led by despots, tyrants and the deranged.

Crafting anything approaching a coherent foreign policy for such an environment is an almost impossible task for a small country with depleted defence forces and ailing public finances. Those calculations are even harder with an impulsive narcissist such as Trump in the White House.

There was an attempt to make sense of Britain’s international standing back in 2021, in the shape of the Integrated Review. But its vision of a “global Britain… shaping the open international order of the future” was already wildly optimistic before it reached the printers.

By 2023 what was coyly labelled as a “refresh” was required, to take account of changes that, it said with delicate understatement, had “happened more quickly and definitively than had been anticipated”. War in Ukraine and growing tensions with China were the real reason, but there was still a declared aim to “shape the international environment”.

For a country that had voluntarily shrunk its influence by leaving the European Union, this veered towards hubris, but perhaps the then government, led by Rishi Sunak, was aware that the Conservative Party would not be in charge of foreign policy, or anything else, for much longer.

David Lammy, Labour’s current foreign secretary, was already beginning to shape a more modest approach to foreign policy. It was, and remains, “progressive realism”, a suitably vague phrase that nonetheless shows how Starmer’s administration is essentially based on pragmatism.

Suggested Reading

Trump is risking a forever war

It was the former Labour foreign secretary, Robin Cook, who articulated his determination that the government’s approach should have an “ethical dimension”, an ambition that, however well-intentioned, was sadly ill-suited to the environment of Cook’s era, and is even less so now.

With Israel continuing its efforts to wipe out Hamas and destroy not only Gaza but all of its citizens, the west was faced with a dreadful humanitarian crisis. But now that Benjamin Netanyahu and Trump have attacked Iran, the risks have multiplied considerably.

Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin seems set on continuing his monstrous onslaught on Ukraine.

As for Trump, he seems to have forgotten that he told the world that his return to the White House would immediately end the war in Ukraine, bring all the Israeli hostages home and generally spread peace – and golf courses – around the place.

But then he forgets much of the nonsense he spouts, and seems not in the least perturbed when his promises translate into pipe dreams. While he remains, though, at least for a while, president of the US, the UK government has little option but to try to engage constructively with him. When it comes to Trump, Britain’s role, like that of many other nations, is essentially reactive.

The former governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, has won much praise for standing up to Trump, but electoral success depended on it and now, as Canada’s prime minister, he must hold that position. Trump may have been jesting when he talked of adding Canada as a US state, but it would have been foolhardy to ignore the threat of US muscle being brought to bear on its neighbour.

The UK, however, is in a different position. The much vaunted “special relationship” with the US has long been heavily one-sided. We need the US, with its mighty defences and massive economic resources, far more than it needs us. There are strong links, however, that persist, including the shared language and overlapping history.

Retaining a strong relationship with the US must form a part of any UK foreign policy, but not at any price. For Starmer, working out where to draw the line will be the stuff of nightmares. There will be many in his party now who will tell him that, by bombing Iran, the US has already crossed it.

His power to exert influence is limited, but it is not zero. The bombing of Iran moves Trump further away from Putin, who is close to Tehran – it is on changes such as this that British diplomacy can get to work, in the interests of Ukraine.

As for Trump, while he is eager to lend assistance to Israel, he seems much less keen on aiding Europe. The imminent Nato summit, which Trump has pledged to attend, is likely to be a tense affair. Many of the nations present will regard Trump’s decision to bomb Iran as an unspeakable act of recklessness – but equally, they will not want to upset the thin-skinned leader of the western world.

Many in the UK, including this writer, wish our prime minister would be more accommodating towards the EU and move faster towards undoing the damage that has been inflicted by the nonsense of Brexit. Trump, however, remains implacably opposed to the EU, as does the political party that currently poses the greatest threat to Labour, Nigel Farage’s Reform.

Starmer was walking his pragmatic tightrope, and his form of “progressive realism” seemed to be serving him well – right up until the moment Trump bombed Iran. The PM now has to decide exactly what the doctrine of “progressive realism” means when confronted with the new reality.