It is Blue Monday, supposedly the most miserable day of the year, and sure enough it’s grey, damp and feels almost as grim as the news that rolls in, relentlessly, from the United States.

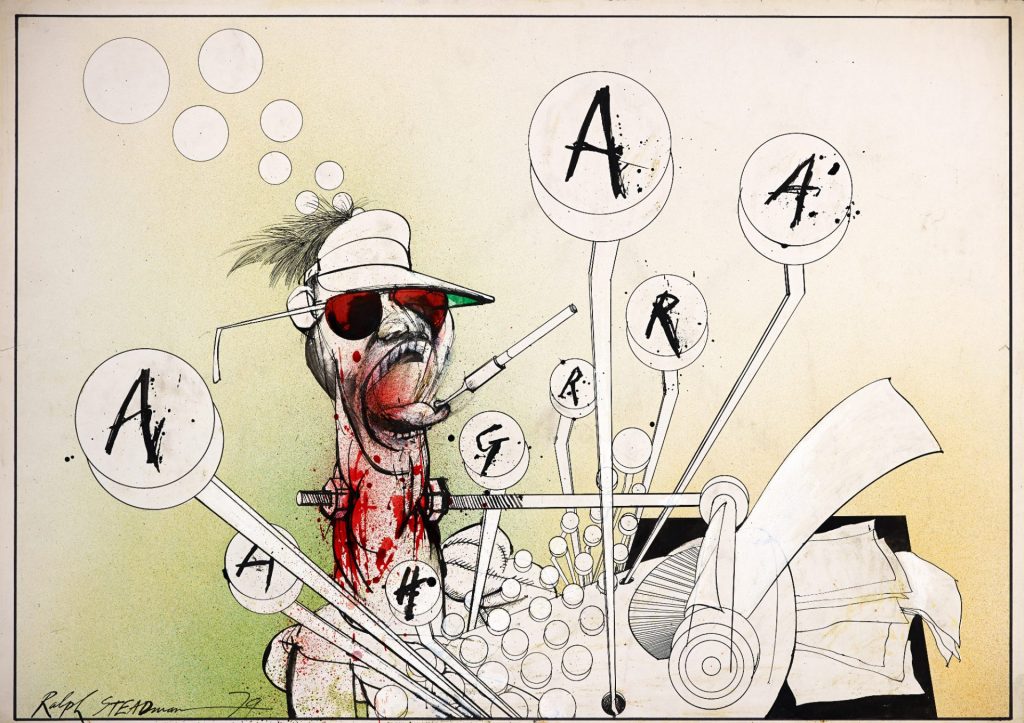

If ever there was a character capable of dispelling the pall, though, it is Ralph Steadman, the artist, satirist and illustrator who has seen it to be his daily duty for 60 years to draw and “confront the Menace [his capital M] – whether that be the local constable or the President of the United States…”

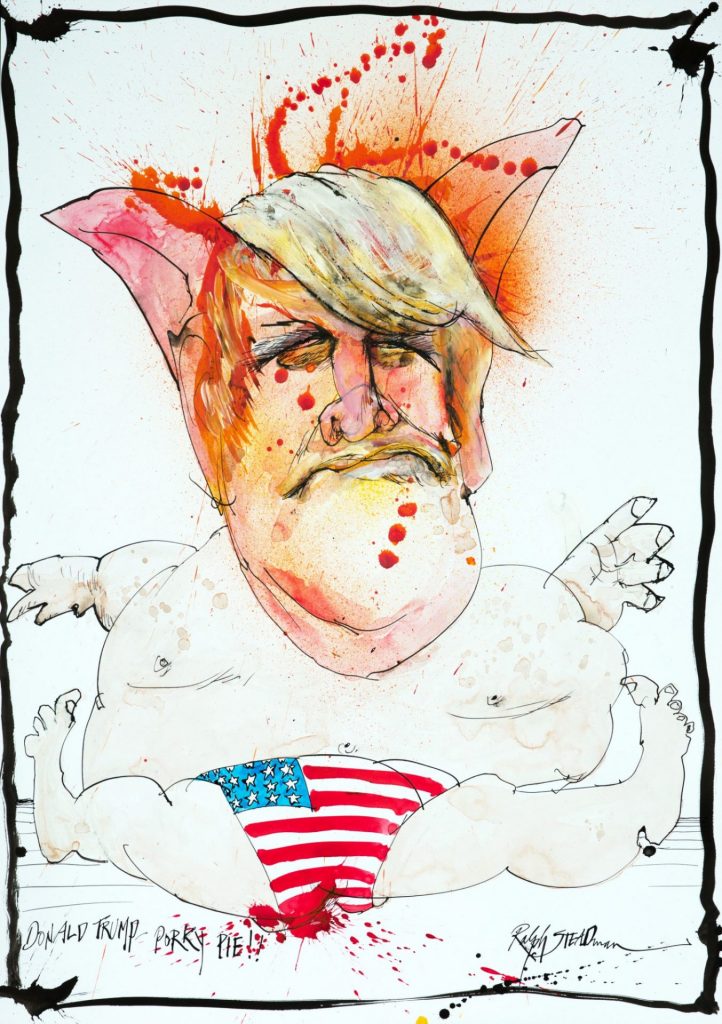

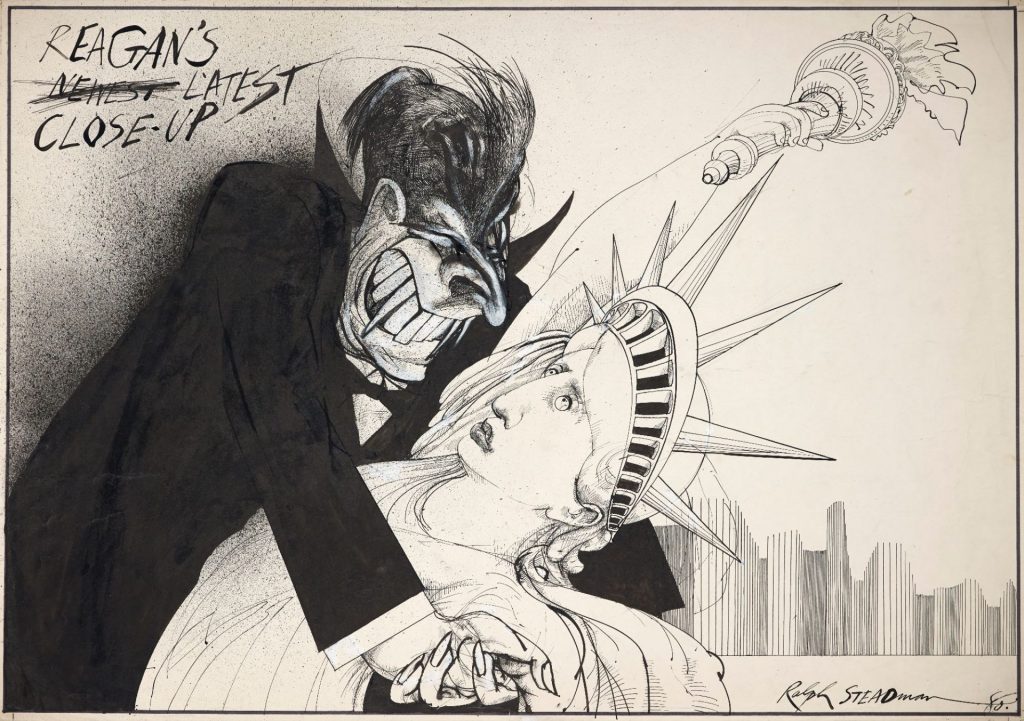

The man who once sketched Ronald Reagan with the face of a vampire, a terrified Statue of Liberty limp in his arms – and Richard Nixon with the face of a pig and hot air (and worse) coming out of his rear end – doesn’t mince words about Donald Trump:

“He is the worst president ever. And the very worst human… and that strange wife of his, she’s so aloof, so distant,” he adds after a pause, pulling a face like a little boy sucking a lemon.

“I have drawn him a couple of times… one can’t imagine a person so awful as him. One of the worst of my lifetime. I call him the Statue of Liberty taker.”

We are seated around an oak dining table in Steadman’s home of four decades, a splendid Georgian manor house in the Kent village of Loose. (It is pronounced like the word “lose” and I know this only because he upset the local Women’s Institute one year with a drawing titled The Loose Women’s Institute).

The house was acquired in 1980 from Richard Boyle, the 9th Earl of Shannon, and Steadman has lived and worked there – and in a spectacular, oak-beamed 16th-century outbuilding he converted into his studio – ever since.

Today, the artist is dressed in a leopardskin-print fleece gilet and a checked shirt. A Santa Fe necktie around his neck has a piece of shell on a brass link hanging from the leather, clearly a kind of amulet. His feet are encased in comfy slippers, a look slightly out of sync with the rest of the still uber-cool vibe.

The table is a work of art in itself, a palimpsest of ink stains collected over decades of book signings and improvised, out-of-studio sketching. His youngest daughter, Sadie Williams, curator and managing director of the Steadman Art Collection, grew up in the house and lives in one wing with her husband and two sons. She is quietly omnipresent and attentive as her dad is staring down the barrel of 90 – his birthday is May 15 – because daily life is not always easy, nor is his memory as sharp.

Her dad, she says a little poignantly, has not been into his studio for a while, walking around it, past it, in the garden, but not into it. Nostalgia? “Maybe, I just don’t think he has the productive drive now.”

Steadman quickly notices that I – and the photographer, Mike Bowers – have Australian accents, and asks Sadie to find her late mother, Anna Deverson’s, diary of their antipodean trip in the 1980s. The UK wine chain, Oddbins, sent him on a six-week tour down under, drawing labels, catalogues, “doing all kinds of things”.

Anna was a prolific diarist, he says, pointing to a bookshelf in the room next door full of her bound notebooks. Later, we see him gently leafing through the neatly handwritten pages punctuated by colour photos that have been pasted in. “Oh, I wish I’d read these when she was alive”, he says quietly to himself.

Who was it that said old age is not for the fainthearted?

The Kentucky Derby

Steadman may be 89, but still he displays flashes of the mischievous, surreal, wild sense of humour he became famous for with his creative partner in artistic crime, Hunter S Thompson.

“Are you going to interrogate me? What is my favourite drawing? Did I used to draw?” he teases before breaking into a made-up gobbledegook language that sends the AI transcription app on my iPhone into spasms.

Theirs was a huge and powerful friendship, one that spanned 35 years until Steadman got a phone call one morning in February 2005 to be told that Thompson had shot himself. He says he always knew Thompson would take his own life, but the shock when it actually happened was huge. “Dad called it the death of fun,” says Sadie. “They were like naughty schoolboys.”

“Hunter was very, very tall, six foot six,” reminisces Steadman, “and when he came to visit us here he kept hitting his head on the doorframe every single time he came through from the kitchen, and every time he’d shout, ‘fucking servants’ quarters’.”

Thompson stayed with Steadman while they worked on their book, The Curse of Lono. Of course, Steadman took him to his local pub, The Chequers Inn, down by the river in the heart of the village. He had privately warned the publican in advance that Hunter’s brandy had to be poured in triple shots, which he diligently did.

“But when I gave him the glass, he said ‘What’s that? A sample’?” he says, laughing at the memory. Steadman ended up buying £150 worth of brandy – about 10 bottles he thinks – and gave them to the publican to stash secretly behind the bar.

(Thompson’s first visit to the UK was rather more chaotic and, reportedly, ended up in scandalous scenes in the posh Mayfair hotel, Brown’s, where he was accused of shooting pigeons on his window ledge with a Magnum .44 and, worse still, of attempting to assault a maid.)

Sadie, a child at the time, remembers Thompson as “immensely tall, chaotic, gruff”: “Mum was on valium by the time he left and I remember refusing to take my coat off… I think it was my security blanket,” she says with a laugh.

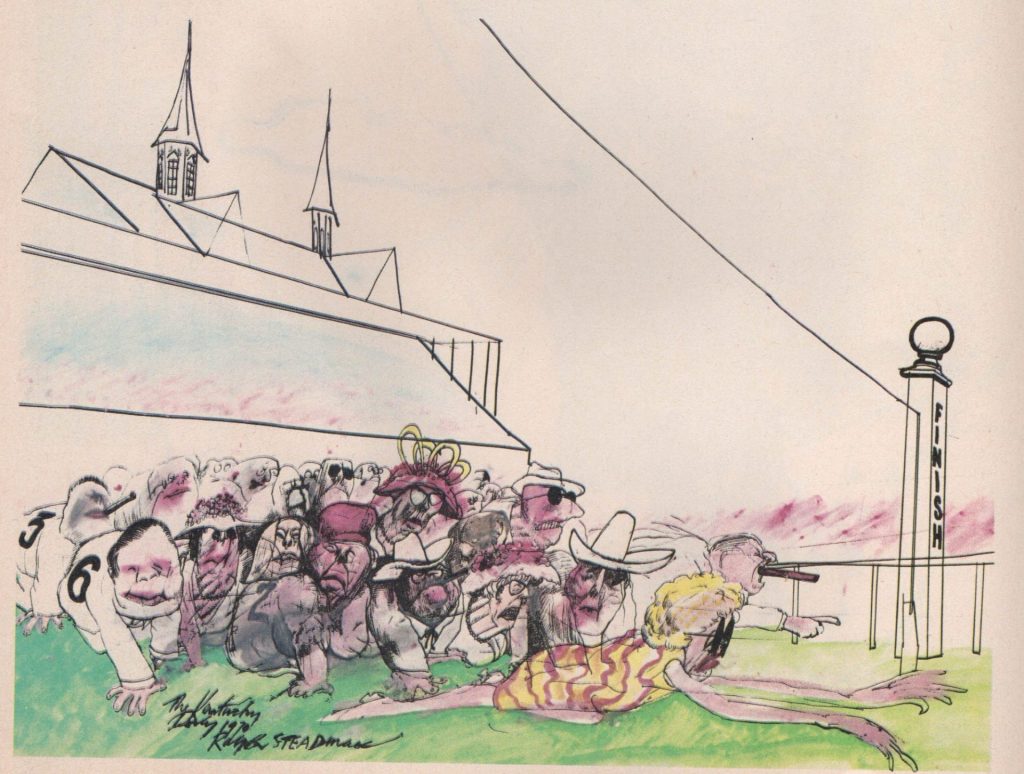

The two men famously first met way back in 1970, covering the Kentucky Derby. Thompson had point-blank refused to work with a photographer and demanded that the magazine Scanlan’s Monthly find him an artist capable of illustrating his weird and wonderful take on the famous horse race. Steadman had a young family of four by then with his first wife, Sheila Thwaite. He had never been to America and the call of new artistic horizons proved irresistible. (The couple divorced two years later.)

The story goes that he left his art equipment, inks and nibs in a taxi the night before he flew from New York to Louisville to meet Thompson for the first time. A friend he had dinner with before leaving turned out to be a rep for the cosmetics company Revlon, and so he set off with a bunch of lipsticks and eyeshadows as a stand-in for paints and colours.

Sadie says her father always managed to create and draw with whatever was at hand, bits of paper, masking tape, chopped-up pages from magazines, once even a tissue she had in her hand. “Everything goes into his work… when I was a child he drew everything, people, things in the park… I grew up surrounded by his art.

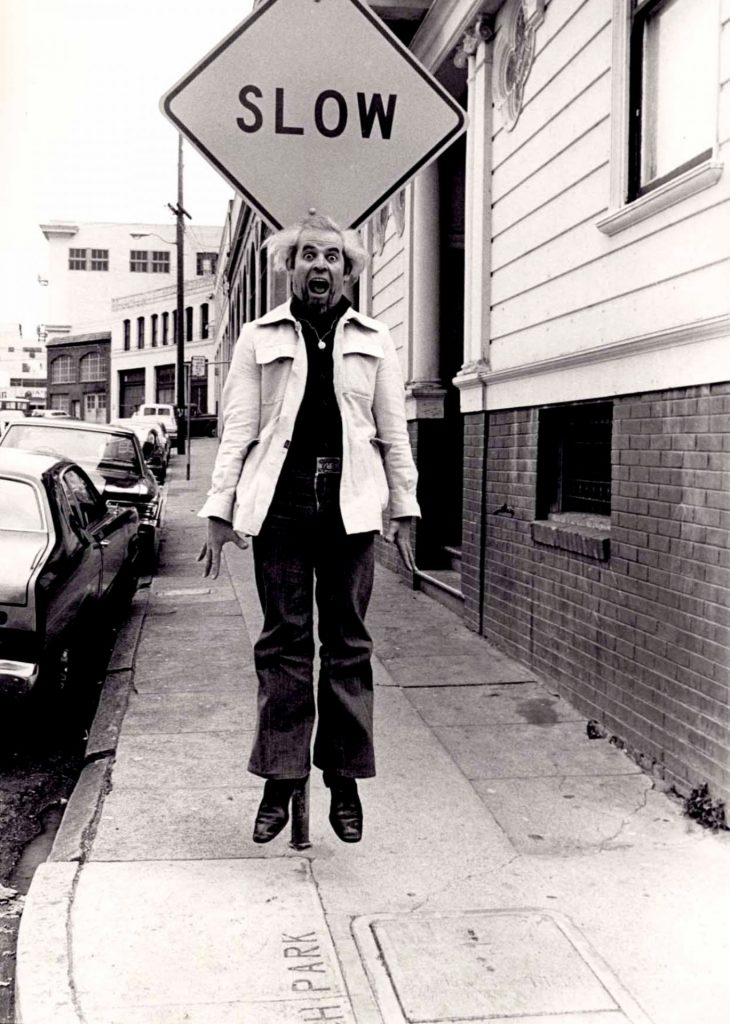

Ralph Steadman at home

“I was much, much older when I realised the place that Dad holds in counterculture and just how important it was and still is.”

Steadman strokes his chin and says that in those days he had what Thompson called “that weird growth” – a goatee – and a thick mane of untamed hair. The writer took one look at him and famously exclaimed, “Holy God, where did they dig you up from?”

“I shaved it off there and then.”

Thompson later wrote of Steadman as a “matted hair geek covered with string warts” and in his article, “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved”, even voiced doubts about Steadman’s capacity to bear up under the “heinous culture shock of being lifted out of London and plunged into a drunken mob scene at the Kentucky Derby”.

Today, Steadman’s hair is white and there is a lot less of it, but his affection for Thompson is ever present and palpable. He concedes with a nod – and Sadie agrees more vigorously – that interview focus on Hunter S can be a little tiring, but still, despite being very, very different people, their bond was strong. A letter from Thompson to his Welsh friend said it all: “Nothing I write feels right without your foul, dehumanised art looking over the words.”

He gets a faraway look in his eyes when I ask him about his childhood and says his dad, Lionel, was a commercial traveller and often used to take him on the road with him while his mum worked in a shop. As a child, he was obsessed not with art but with constructing aeroplane models, and had dreams of designing and making real aircraft.

Sadie says she came home from school one day to find TV crews in the garden and her dad on the roof ready to trial-fly one of his own-design planes.

Steadman did in fact work for De Havilland as a trainee engineer in his late teens, but says bluntly, “I hated the factory life”. Unsure of his future path, he found a job working at Woolworths in Colwyn Bay. “My headmaster from Abergele grammar school saw me in the street outside and said I could have made something of myself if I’d stayed at De Havilland… instead I was sweeping floors in Colwyn Bay.”

Somehow, the cruel words of the school principal, Dr Hubert Hughes – a name he never forgot and whom he later caricatured with scathing sharp lines – only served to ignite his ambition and the dream of somehow making a difference in the world. During National Service, he served as a radar operator with the RAF and it was then that he saw an ad – “You too can learn to draw and earn pounds” – that piqued his interest. “That was the Percy V Bradshaw Press Art School,” he exclaims excitedly, a name he repeats out of the blue – and often – throughout our visit. Later, frustrated by the limits of his skills, he enrolled at East Ham Technical College to practise the discipline of drawing and met his much-loved mentor, Leslie Richardson, who encouraged him to enrol in the London School of Printing. During this period, he began to draw cartoons for regional papers, moved on to the New Statesman, Punch, the Times and the newly established Private Eye. His illustrations of Alice in Wonderland made waves in publishing and saw him turn White Rabbit into a frenzied commuter, the Mad Hatter into a union leader and the caterpillar into a John Lennon lookalike surrounded by a fug of smoke.

“Do you know Lewis Carroll’s real name,” he asks briskly, and when I remember Charles Dodgson, he rewards me with a wide smile.

Of course, his big international break came with the collaboration with Thompson and Rolling Stone and together, they pioneered the legendary booze and drugs-fuelled stream-of-conscious reportage that became known as gonzo journalism. (He remains listed on the masthead as Ralph Steadman, Contributing Editor, gardening).

His work, however, didn’t end there: the gonzo period broadened into an eclectic and prolific artistic life, ranging from more books for children, including Treasure Island, to myriad literary classics, from Animal Farm to The Grapes of Wrath. He has collaborated since with many greats, including Ted Hughes and Brian Patten, designed sets for the theatre and ballet, produced portraits for a boxed set of Breaking Bad, although one of the stars (we’re not allowed to tell you who, but have a guess) never appeared because the actor refused to OK her likeness. More recently he has worked on a series of animal-based books with the conservationist Ceri Levy.

Suggested Reading

A beach holiday in the Sudanese warzone

The Steadman archive contains some 16,000 works, and commercial collaborations are equally eclectic: last November the Formula 1 champion Lewis Hamilton’s Plus44 clothes label chose some of his images, with Steadman saying he’d “spent decades spilling ink across pages – now it’s landed on clothes”.

A touring exhibition spanning his 60-year career and titled Ralph Steadman: And Another Thing kicked off in Washington back in September 2024 and has been on the road ever since. It is due to land on the West Coast of the US at the Torrance Art Museum in California in March.

I ask his daughter and curator – the girl he mischievously registered at birth as Sadie Anna Cinderella because he thought it might be fun for the poor, bored passport officers who just “stamp stamp stamp every day” – if she has a favourite work, and just love that she says Emergency Mouse, Bernard Stone’s gentle celebration of hospitals, told through the eyes of a little boy who is sick and admitted for care with his pet mouse.

We had been talking about favourites while leafing through Steadman’s 1982 book, I, Leonardo, in which he explored his obsession with the original renaissance man and wrote in the first person of the world as he imagined Leonardo saw it. The original drawings are spectacular, executed at an unexpectedly large scale, on A1, and as Sadie pulls them out of a drawer in the studio, one by one, to show me, the technical brilliance of his formal art training glows.

Does Steadman himself have a favourite? “Dad’s is Leonardo…” she says.

And what does the artist himself think?

“Mmm, I will write something down. Drawing? I can’t do it any more. Did I used to draw?” he says, a tease of a twinkle in his eye.