Every now and then, fate smiles on the patient traveller and so it was at 8am one morning that we joined an already 100-strong queue to attend Mass in the newly reborn Notre-Dame de Paris.

Gathered around the baptismal font before proceeding to the altar, a man of the cloth asked us where we had come from? “Australia! That is a long way.” With that, Father Guillaume Normand, the new vice-rector, offered to take us on a special tour of “his office”.

Walking into Notre Dame is a breathtaking experience at any time, but as our eyes adjusted to the lower light, the sheer enormity of the restoration process came into focus. Five and a half years have passed since the catastrophic fire and $900m – much of it in donations – has been spent on restoration. Work continues outside, but inside, it is as if the stone of the vast, soaring arches and chapels has been dipped in sunshine.

I have seen Notre Dame several times and remember it as imposing, sombre, dark, its walls a palimpsest of soot, candle smoke and city grime. But now the stained-glass windows gleam and the medieval paintings glow with a new depth. The lightness is both shocking and uplifting, and, said Father Guillaume, Parisians themselves are still getting used to the new, freshly scrubbed look.

“But there are 1,000 years of stories in here,” he says as he walks. “Things that link the ancient past with the present, architectural changes, tapestries, paintings, furniture that make the 11th century talk to the 21st century. This change makes more story”.

Looking up to the very top of the vaulted arch of the nave he pointed out a series of small holes – once used for wiring – but left unfilled after the first firemen entering the building in the wake of the blaze reported “a surreal and unforgettable experience”.

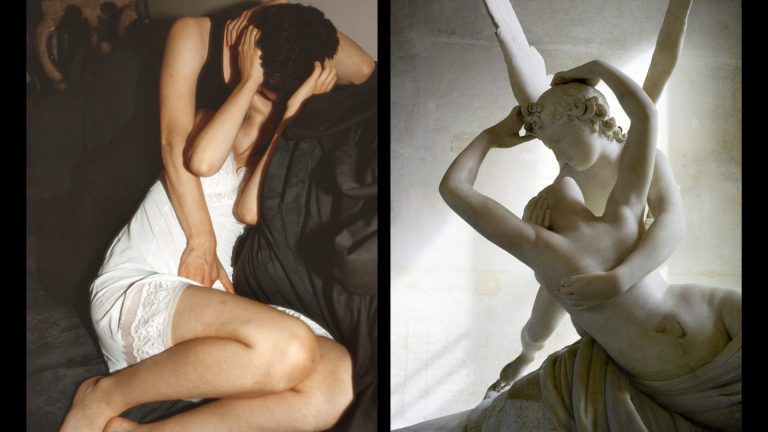

“They said there was a strange calm and silence in an enormous space usually filled with noise and voices and people and then the strangest thing happened when fine ash found its way through the little holes and it was like black snow falling and falling from the heavens.” And so, the holes are left there to bear witness, much like the blob of molten lead that fell from the flaming roof and fused itself into the open palm of the dead Christ in Nicholas Coustou’s Pieta’ sculpture below.

Suggested Reading

Photography in Vincent’s town

Restorers did not touch it either: “It has been left there, in the place where it fell like Christ’s wounds – a reminder of the fire.”

Historic artistic treasures have been joined by new works commissioned from contemporary artists. The uber modern austerity of the bronze baptismal font, altar, tabernacle, pulpit and cathedra (bishop’s chair) designed by Guillaume Bardet speak back across the centuries to the splendid, painted medieval wooden sculptural panels that surround them. A woman, Ionna Vautrin, was chosen to design the 1,500 new chairs, their backs deliberately kept low, she said, to emphasise the Cathedral’s “dizzying verticality”.

The new visitor route, Father Guillaume tells us, has also been carefully redesigned for a more coherent, chronological experience but also a more symbolic one, starting at the central portal of the Last Judgment and proceeding clockwise, past paintings and sculptures depicting the Old Testament, scenes from the life of Christ through to the resurrection.

“There is spiritual significance as we walk from the north that is dark towards the south and the light,” he says. The cathedral’s most important relic, the crown of thorns, long housed in the treasury, is now contained in the centre of a spectacular, sunray-shaped reliquary created by the French architect Sylvain Dubuisson.

Every day since the cathedral reopened its doors, some 32,000 people file into the sacred space and 12-13 million people are now expected every year. Pointing up once again, he marvels at the cerulean blue ceiling of the central vault crowned with freshly painted gold stars: “This is where the spire fell down, crushing the roof and taking the second vault with it… and yet the Pieta’ and the [14th-century] Virgin and the Child, miraculously, survived”.

As we head out, father Guillaume asks us to gaze at the sculptural Last Supper and guess which apostle we think might be Judas.

“No, it’s not the one at the back, nor the one looking away, nor the one holding his head in his hands,” he said. “Judas is the one at Christ’s left, made to look straight out at us and holding the bread in his hand.” He is the last of the 12 any of us would have chosen.

Father Guillaume says quietly that his holding of the bread signified redemption: “The medieval sculptors wanted us to know that if Judas could be forgiven, then there is hope for us all.”

Paola Totaro is an Italian-Australian journalist based in London