The corruption scandal and political crisis in Ukraine which Volodymyr Zelensky faced last week were quickly kicked off the agenda by a new thing: the “US’s peace plan”, which some voices said was first written in Russian. As the US and Ukrainian delegations met in Geneva, European leaders drafted their own “28 points plan”, crossing out one important point and changing many others.

The “US’s” offer was a retread of Putin’s main demands, including that the Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk regions should be internationally recognised as “de-facto Russian”, including those parts currently controlled by Ukraine. Ukrainian troops should retreat completely from those regions, making that territory a “neutral demilitarised buffer zone”.

Kherson and Zaporizhzhia would be frozen along the line of contact and army personnel would be capped at 600,000. Another stipulation was that “all Nazi ideology and activities must be rejected and prohibited”. It should be recalled that the “demilitarisation and denazification” of Ukraine was one of the main goals of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

The agreement will be enforced by the “US-Russia working group” – yes, the US will be allied with Russia, the aggressor state which started this war, in order to force Ukraine to capitulate. As they say in Ukraine, “ask the wolf to guard the sheep”.

In addition, the agreement demands that Ukraine must “enshrine in its Constitution” the fact that it will not join Nato, and that the organisation must include a provision in its statutes that it will not admit Ukraine and that no Nato troops should be stationed in Ukraine. In other words, Ukraine must be left vulnerable to the next military aggression.

As Ursula Von der Leyen has said, a just and lasting peace for Ukraine must have three core elements: a recognition that borders cannot be changed by force; that any limitations on Ukraine’s armed forces should not leave Ukraine vulnerable to future attack; and that “the centrality of the European Union” in securing peace for Ukraine must be “fully reflected”. The US’s proposal is far from that.

The EU has offered to put $100bn into Ukraine’s reconstruction. Also, Europe is named as a part of the “comprehensive non-aggression agreement” along with Russia and Ukraine, which means that the US is distancing itself from security on the continent. It is also edging away from Nato, saying it will be “moderating a dialogue” between Russia and Nato “to resolve all security issues”, while being the main Nato power at the same time.

The US-Ukraine joint statement after the first round of Geneva talks said that Ukraine and the US will remain “in close contact with their European partners”, but the final decisions will be made by the presidents of Ukraine and the US.

Trying to reassert themselves in matters of Ukrainian and European security, the EU leaders attempted to push back the plan, which is politically and commercially beneficial for both Russia and the US, but threatening for Ukraine and Europe.

The European plan removed the statement that “Nato will not expand further”, saying that: “Ukraine joining Nato depends on consensus of Nato members, which does not exist”. Also, it says that Nato troops will not be permanently stationed in Ukraine “in peacetime”, which opens the room for discussion about what happens during wartime.

Suggested Reading

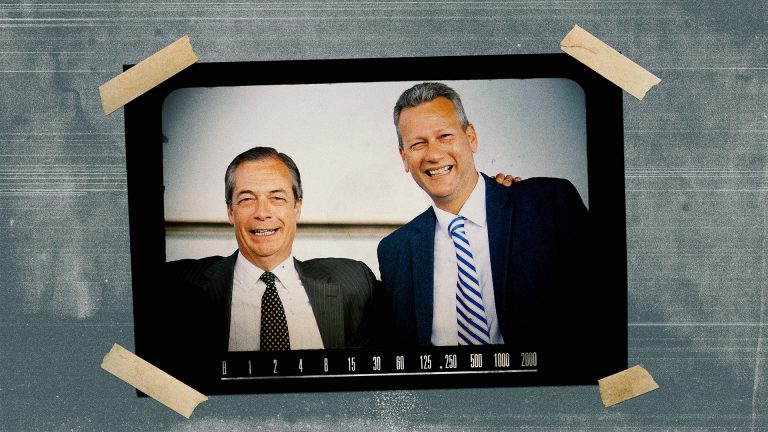

Nathan Gill, the tip of a much bigger iceberg?

Europe proposes that Ukraine’s military personnel cap should be 800,000 troops, and demands a guarantee from the US mirroring Article 5. With the US trying to leave peace on the continent to Russia, EU and Ukraine, that seems hardly possible.

In case Russia invades Ukraine, sanctions will be reimposed and there will be a “decisive” (the US version) or “robust” (EU version) military response (details remain unknown).

Both documents say that if Russia agrees, it will reintegrate into the global economy, rejoin the G8, will be free of sanctions and will begin a period of long-term economic cooperation with the US.

The US’s appetite for collaboration with Russia is large: it includes projects in energy, natural resources, infrastructure, artificial intelligence, data centres, rare earth metal extraction projects, and one of Trump’s special areas of interest – the Arctic.

Even Russian frozen assets will benefit the US. The “plan” says that

$100bn of those will be invested in “US-led efforts to rebuild and invest in Ukraine”, with 50% of the profits from the venture going to the US. And the remainder of those funds will go to a “separate US-Russian investment vehicle”. The EU says Russian sovereign assets should remain frozen until Russia compensates Ukraine.

The US has its interests in Ukraine as well: it wants to “jointly rebuild, develop, modernise, and operate Ukraine’s gas infrastructure, including pipelines and storage facilities”, as well as extract minerals and natural resources.

The EU does not object to the US’s interests in Russia and Ukraine, but it wants more security guarantees for Ukraine from the US, less pressure on Nato from Russia, as well as recognition of Ukraine as a sovereign state, which includes being free to make decisions on which alliances to join. And it looks like this component is seen differently on either side of the Atlantic.

Nina Kuryata is The Observer’s Ukraine editor