There is no Nobel prize for philosophy. That’s a shame.

Henri Bergson, Bertrand Russell, and Albert Camus all won the Nobel for literature, not philosophy. Jean-Paul Sartre refused it in 1964 because he thought it would compromise his independence. He also said winning it would torture him because of the large sum of money that came with it.

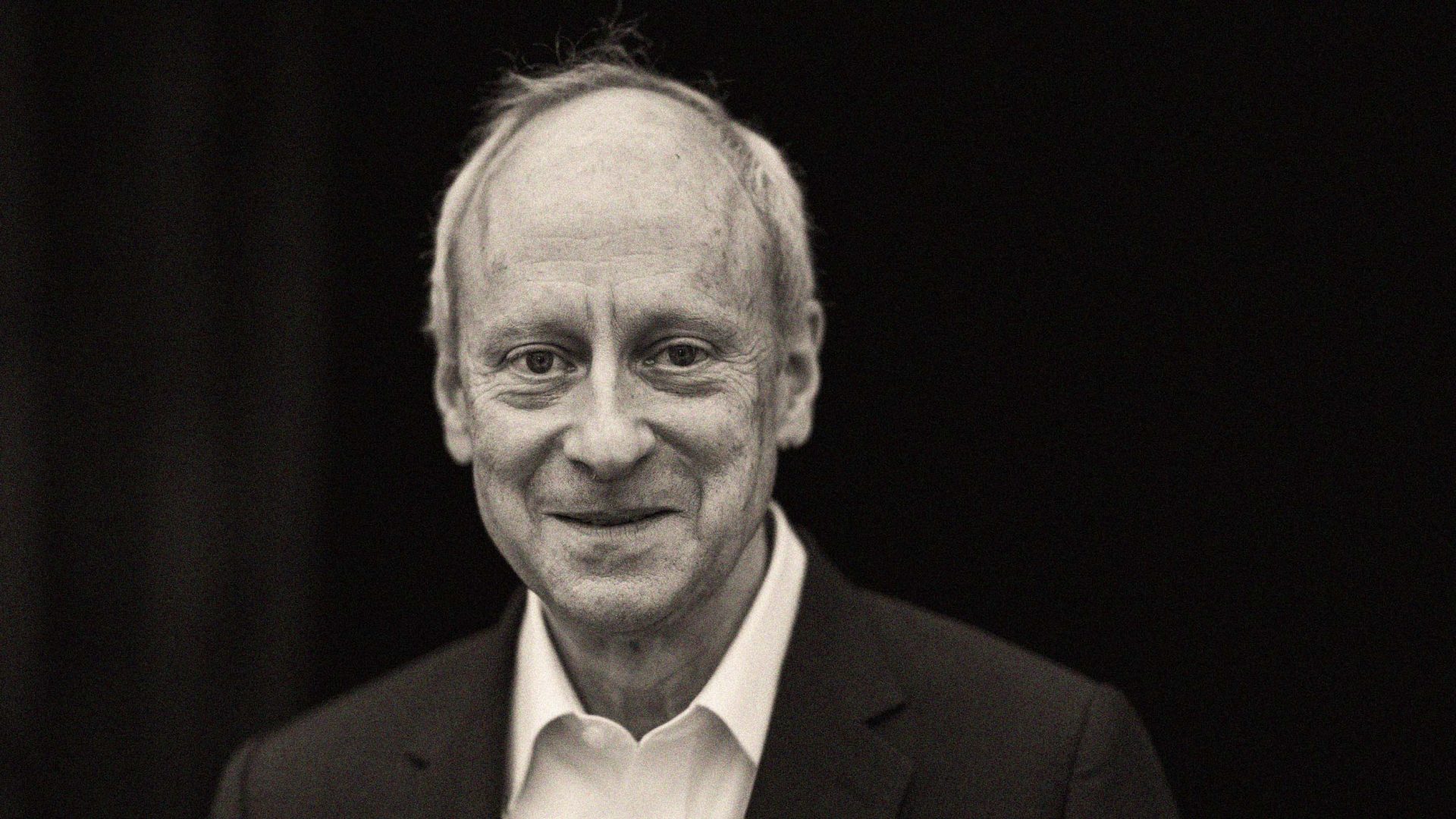

Last week, the Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel won the closest philosophy has to the Nobel prize, the annual Berggruen prize for philosophy and culture. Since 2016, the billionaire philanthropist Nicolas Berggruen has paid out a million dollars to a thinker “whose work has led us to find wisdom, direction, and improved self-understanding, in a world being transformed by profound social, technological, political, and economic change.” This year, a jury of mainly non-philosophers chose the winner.

Most Berggruen winners have been established academic philosophers whose work in ethics and public philosophy clearly fits the brief, including Charles Taylor, Martha Nussbaum, Onora O’Neill, and Peter Singer. There have been quirkier choices too, most notably Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2019, and the Japanese deconstructionist philosopher/literary critic Kojin Karatani in 2022. Some plausible candidates for the award, such as Amartya Sen and Kwame Anthony Appiah, may have inadvertently disqualified themselves from winning by having served on the prize jury.

Sandel, like most people suddenly receiving a million dollars, doesn’t seem to have been tortured by his win. He has already declared his intention to donate part of the prize money to The Babayan Story Project, a civic education programme for children available in multiple languages that he and his wife, Kiku Adatto, set up.

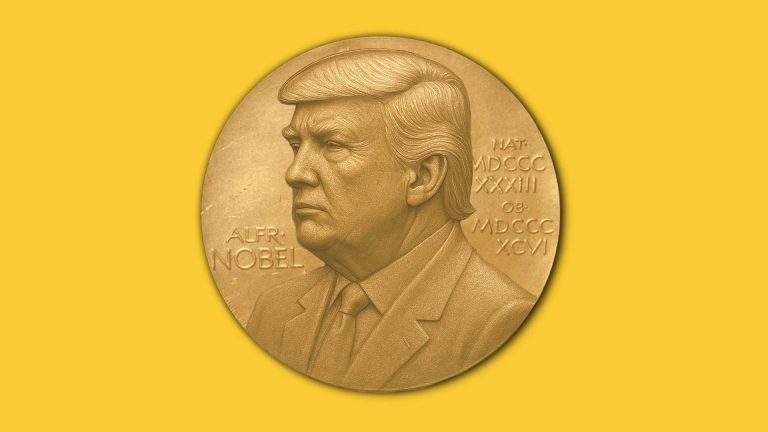

Suggested Reading

Why Trump should never be given the Nobel peace prize

The 2021 prize-winner, Peter Singer, gave the full million dollars away. Half went to charities aiding people in extreme poverty, a third to organisations working to alleviate animal suffering, and the rest to other effective causes.

Sandel has many claims to fame, including allegedly being the physical model for Montgomery Burns in The Simpsons. This is not as implausible as it sounds since many of the show’s writers are Harvard alumni.

Academically, Sandel cut his teeth as a critic of John Rawls. He gave what’s come to be known as a communitarian critique of A Theory of Justice. Rawls seemed to imply that there are universal individual rights that we can arrive at by reflecting on what sort of society we would design if we didn’t know our place in it. Sandel argued that ideas of the common good partly arise out of social and historical conditions and that kind of abstraction from our real position in society isn’t possible.

At Harvard, Sandel became a celebrity with his Justice course. In a series of well-crafted and engaging lectures, he combined some of the key ideas from the history of ethics with on-the-hoof-interaction and debate with his student audience. This is part of his mission to recover the lost art of democratic argument and his admirable desire to make philosophy relevant to public debate on questions that matter.

His focus was “What’s The Right Thing to Do?” The course, Harvard’s first to be available freely online and on television, has reached many millions of people across the world and is still available here.

In the UK, he’s probably better known for his 2009 Reith Lectures “A New Citzenship”, which centred on the common good, and for his Radio 4 series The Public Philosopher. No other philosopher in the history of the subject has had this kind of reach while alive, and very few have posthumously. On tour, he fills football stadiums.

Critics might say there is something of the Derren Brown about the way Sandel guides his audiences through philosophical issues in a lecture. He invites audience answers to questions, but whatever response is given slots neatly into a pre-organised intellectual journey, heading for a particular conclusion. The audience has the illusion that they are contributing to an unfolding exploration, but the direction of travel has all been pre-planned and masterfully stage-managed. That might be an unfair criticism, since it’s hard to see how else he could handle this.

As well as being a compelling performer, Sandel is a first-class writer. He’s a kind of anti-Slavoj Žižek in that respect. Whereas the Slovenian neo-Marxist bamboozles readers with rapid-fire volleys of jargon, paradox, and pseudo-profundity, Sandel takes us through the issues in lucid prose.

You know where you are with him. You don’t have to agree with him to see why he won this prize.