Who’s your favourite philosopher? That seems like an innocuous question. It’s one I get asked a lot. But I always struggle to answer it. I usually have a go.

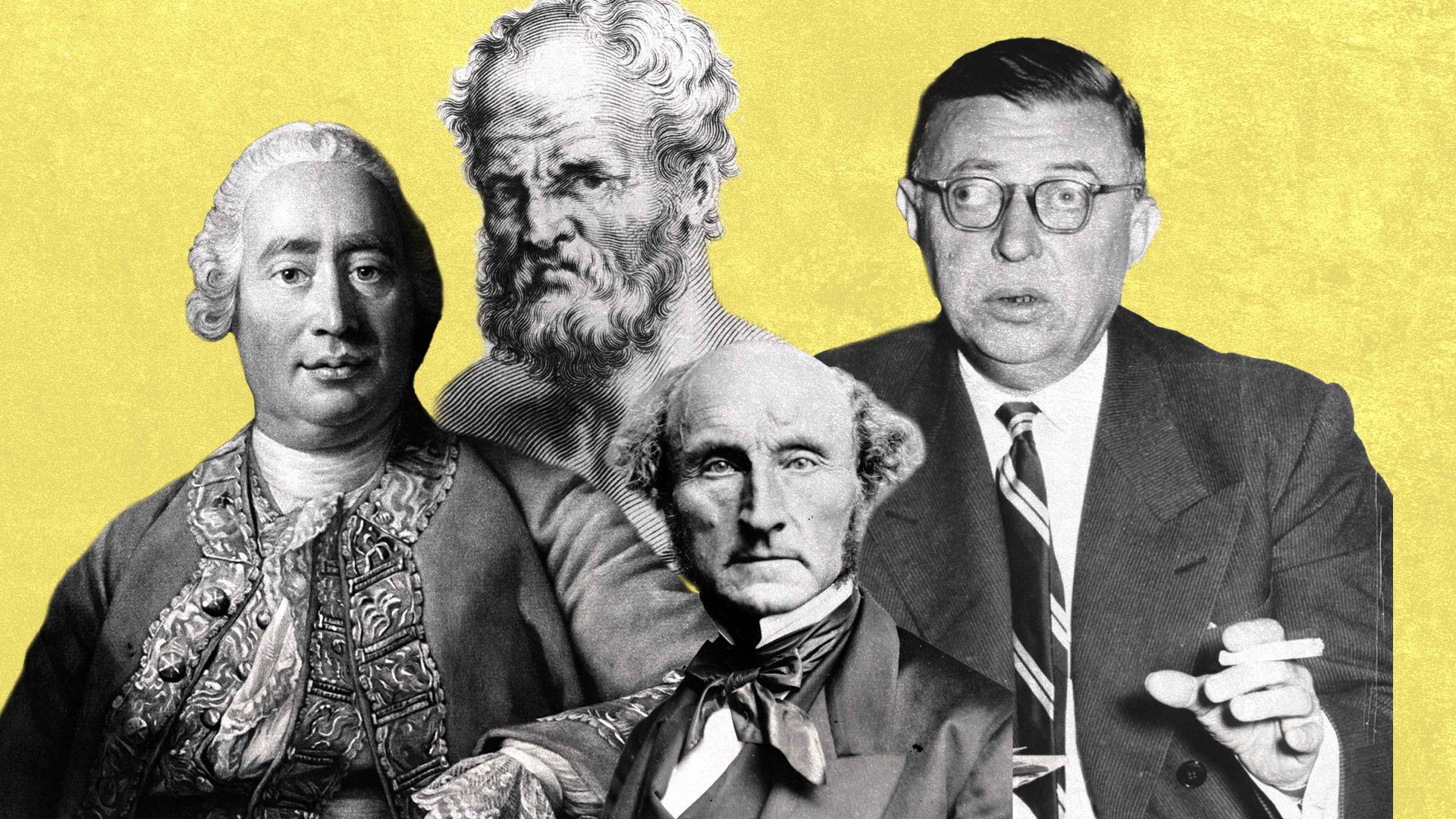

I might respond that I like Diogenes the Cynic for his refusal to be bound by convention, and for the way he enacted his philosophy like some kind of performance artist. He lived in a barrel (or more probably a large earthenware jar) and refused to kowtow to Alexander the Great, the most powerful person in the world, when he visited him, asking him to move his shadow.

I like Diogenes’ cosmopolitanism, too, his declaration that he was a citizen of the world. But I’m not going to follow him; I’m not going to masturbate and defecate in public (as he allegedly did) and get rid of all my possessions.

I’m also a deep admirer of the 18th-century Scot David Hume, for his acute intelligence and wit, and particularly for his posthumous Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, where he lacerated the main philosophical arguments used for the existence of God.

But it turns out Hume was a racist, so I can’t give him an unconditional endorsement.

I have a special affection for John Stuart Mill, particularly On Liberty, his “philosophic textbook of a single truth”. I love chapter two, which is about the value of free expression.

There, he distinguished dead dogma from living ideas, declaring, “Both teachers and learners go to sleep at their post as soon as there is no enemy in the field”.

Mill’s point was that extensive freedom of expression is a condition of having your thoughts challenged, and that unless that is done, preferably by someone who genuinely disagrees with them rather than is playing devil’s advocate, they remain prejudices.

It matters not just what you believe, but why you believe it. Far better to be able to defend your views against opposing ones than simply to inherit them.

He championed free expression up to the point where someone encourages violence through their pronouncements and maintained that offence is distinguishable from harm. But Mill, like Hume, had some patronising views about non-Europeans, and only wanted to reserve the extensive individual liberty he championed in “experiments of living” and in speech and writing for the “civilised”, and not for races “in their nonage” (ie those in a state resembling childhood).

Suggested Reading

How the world forgot James Hutton

Jean-Paul Sartre was a very influential figure for me. I first read his novel Nausea as a young teenager after learning about it from Colin Wilson’s book The Outsider.

There are passages in Sartre’s Being and Nothingness that are quite brilliant. His descriptions of Bad Faith, that special kind of fear of one’s own freedom that leads people to pretend that they’re constrained in what they can do, have stayed with me, as has his account of how absences are as much a part of our experience of the world as the things and people who are present.

I admire his immense creative energy and his willingness to write on almost any topic or in any genre, including novels, plays, film scripts, and biographies. He seemed to have enjoyed life much more than most philosophers do, too.

But much of his later philosophical writing is convoluted and barely intelligible (partly the result of using amphetamines). And his political instincts were appalling.

Sartre was an apologist for the Soviet Union and for Mao Zedong (he did, though, oppose the Vietnam war and was a staunch opponent of French colonialism). I feel I ought to prefer Simone de Beauvoir, who was a better philosopher in many ways, but my early love for Sartre’s existentialism is hard to shake, even though I now believe his existentialism rests on extravagant wishful thinking about the degree to which individuals have choice over their lives.

So, these are the candidates that spring to mind for my favourite philosopher, and I can’t endorse any one of them without reservation. I might on another day have included Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Arthur Schopenhauer. They all had feet of clay, too. Sadly. And I only admire some aspects of what any of them wrote.

But what I have noticed in writing this column, is that no thinker on my shortlist (with the exception of Nietzsche, and then only very briefly) was ever a university professor. That might be a coincidence, but I doubt it.

I believe it gave them greater freedom to be original, authentic, and interesting. It allowed them to become who they were.