The lives of philosophers have provided rich pickings for millennia. One of the best-known sources for information about Ancient Greek philosophers was written in the third century CE by Diogenes Laertius. In his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, this Diogenes (not to be confused with Diogenes of Sinope, the Cynic who lived in a barrel and who features in Laertius’s book) drew on a long tradition of storytelling about how philosophers lived and died.

Laertius’s book has been criticised for being gossipy, neglecting the philosophy for the sake of a good anecdote. Yet it’s partly for the gossip that it’s still read today.

There’s a risk here for modern biographers too. Leave out juicy details (many of which are hard to corroborate), and you get a dry chronological exposition of a thinker’s intellectual development. Yawn. Include too much, or get seduced by the myths, talk to too many of their lovers, dwell on their quirks and tics, and you’ll end up being sensational and misrepresenting who the thinker essentially was.

It’s easy to give too much weight to aspects of someone’s life that happen to have been preserved in letters and diaries, or in other people’s unreliable memories. Speculate too much about what is unsubstantiated, though, the gaps in the records, and you’d be better off writing a novel.

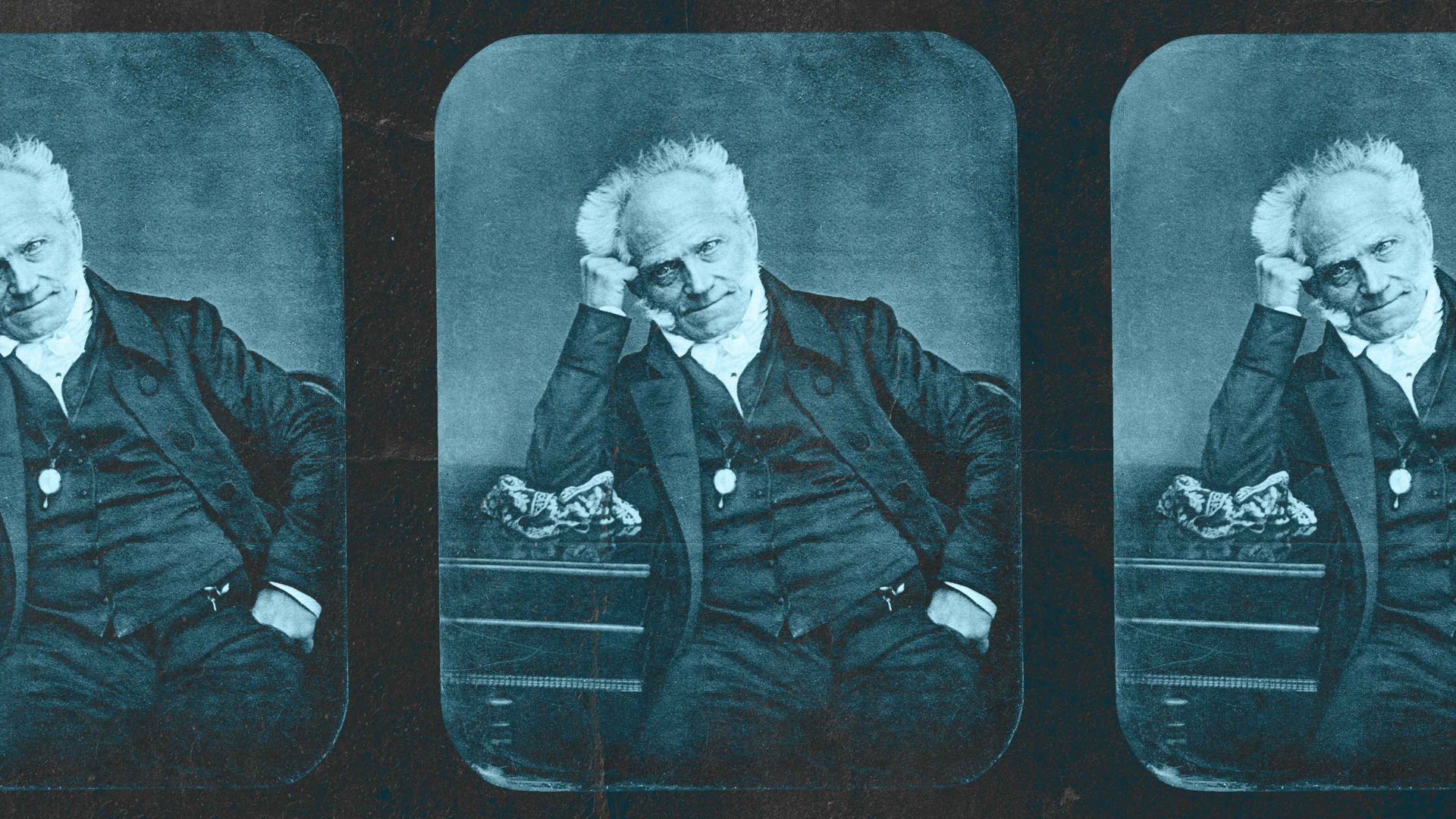

David Bather Woods, whose biography of Arthur Schopenhauer has just been published by University of Chicago Press, has got the balance about right. Anyone wanting to learn more about this intriguing pessimist, his life and times, and his unsentimental angle on existence should now begin here.

Schopenhauer was an inspiration for many great writers as well as philosophers – Thomas Hardy, Thomas Mann, Samuel Beckett, and Jorge Luis Borges were all in awe of him – and Bather Woods shows us why. But at the same time, he doesn’t shy away from Schopenhauer’s flaws, including his racial prejudices and undoubted sexism.

Like many of the most original philosophers, Schopenhauer spent much of his life at a distance from the academy. David Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Søren Kierkegaard, John Stuart Mill, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, all operated outside the constraints of the university system.

His father’s death (probably by suicide) when Schopenhauer was just 17 meant he inherited enough money to live as a man of letters for the rest of his life, and so (not unlike Kierkegaard in this respect) was able to resist mainstream intellectual pressures and follow his own distinctive path as a thinker.

Suggested Reading

CS Lewis and the truth about grief

Schopenhauer’s general philosophical outlook was exceedingly glum. “Life swings like a pendulum back and forth between pain and boredom,” he declared. Joys and pleasures are scarce and short-lived; we are trapped in a relentless cycle of desire, which even if fulfilled only leads to further unfulfilled desires. Either that, or we get stuck in the doldrums caused by absence of desire; life then feels intolerable because there is nothing to live for.

Restlessness, suffering and inertia characterise the human condition. He genuinely believed that it was better not to have been born. Nevertheless, his pessimism was not as dark as it could have been, since it was redeemed by the belief that human beings are capable of compassion and that this is a mark of our humanity.

Unusually for his time, Schopenhauer extended this compassion towards non-human animals. He kept poodles and was appalled whenever he saw a dog chained up: so appalled that he felt glee when he read that a person had had his arm torn open by his chained dog.

He made almost daily visits to an orangutan that was temporarily on display at a Frankfurt fair, stared deeply into its eyes, and felt this kind of ape must have been an ancestor of humans. Although an early advocate of animal welfare, he didn’t take the step of becoming a vegetarian because he (falsely) believed that “one cannot exist at all without eating meat”.

Friedrich Nietzsche, on whom Schopenhauer was an early influence, chided him for being a pessimist who played the flute. For Nietzsche this was hypocrisy. Schopenhauer should have been moping around in a melancholic depression. How could he devote hours a day to such a playful instrument when he believed life was so dark?

Bather Woods’s biography provides an answer to this. At the heart of Schopenhauer’s pessimistic philosophy, he argues, is a belief in universal solidarity. We are all fellow-sufferers in this absurd unchosen world of pain, and so should feel compassion for one another.