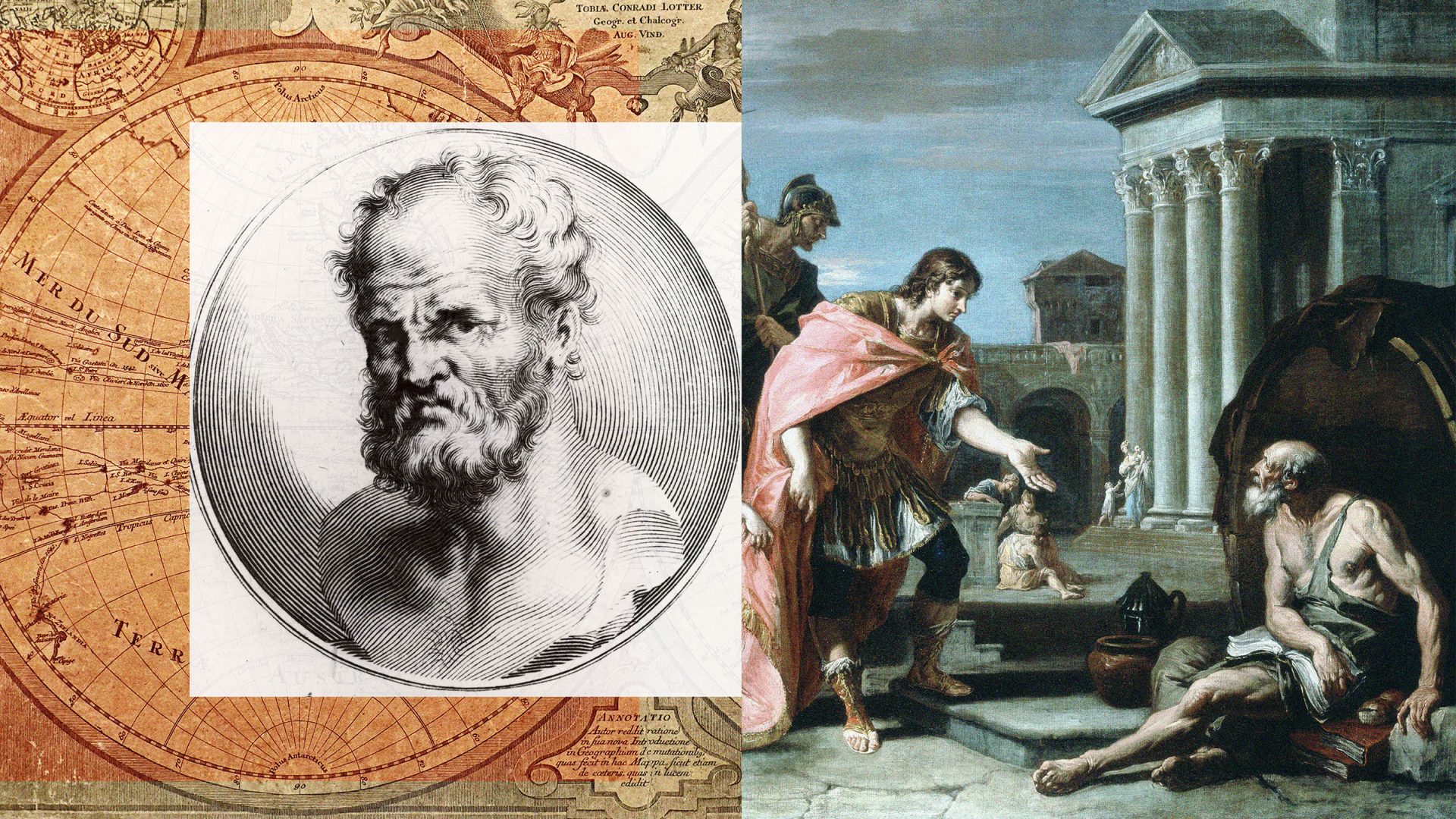

As regular readers of this column will know, Diogenes the Cynic is one of my favourite philosophers. Apart from being a kind of Ancient Greek performance artist, famous for having requested Alexander the Great to move his shadow, he was the father of cosmopolitanism.

When asked where he was from, he’d reply, “I am a citizen of the world”. Ironically, he’s still known as Diogenes of Sinope, not Diogenes of the World, although that’s partly to distinguish him from Diogenes Laertius, the third-century author of Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. For Cynics like Diogenes of Sinope (and of the World), cosmopolitanism meant rejecting local customs, which they saw as merely conventional, and following instead natural ways of living that are universal.

As the world lurches back towards nationalism, antagonism, and isolationism after a period of trade-driven exchange and greater collaboration, should we now abandon cosmopolitanism, the philosophy of many liberals? Should we replace it with a form of communitarianism that cares for its own, perhaps just those within its national borders, a form of tribalism that is less concerned about what happens to people in distant lands? Or should we perhaps go even further and embrace all-out individual selfishness like the guru of neo-liberalism Ayn Rand? No.

Back in February, JD Vance interpreted the Christian injunction to love thy neighbour to mean you should love your neighbour first and be less worried about caring for those beyond national borders than liberal humanitarians tend to be.

That was an unorthodox interpretation of something Augustine wrote on ordo amoris (the correct order of love). Vance’s interpretation seemed to imply, conveniently, that it might be all right never to get around to helping others in distant parts of the world, even though their lives could depend on that help.

More plausibly, though, Christianity is a radically egalitarian religion that invites us to love every human being wherever they live. Shortly before his death, Pope Francis took time to set Vance straight on this: “the true ordo amoris that must be promoted,” he explained “is the love that builds a fraternity open to all, without exception.”

That sentiment, with or without a religious underpinning, lies behind the ethos of this magazine, reborn last week as The New World. Other people matter, regardless of where they are. We are interconnected, and in an important sense part of one world. And we care about one another and want to understand more about other perspectives than the national-centric ones we are so often fed.

Suggested Reading

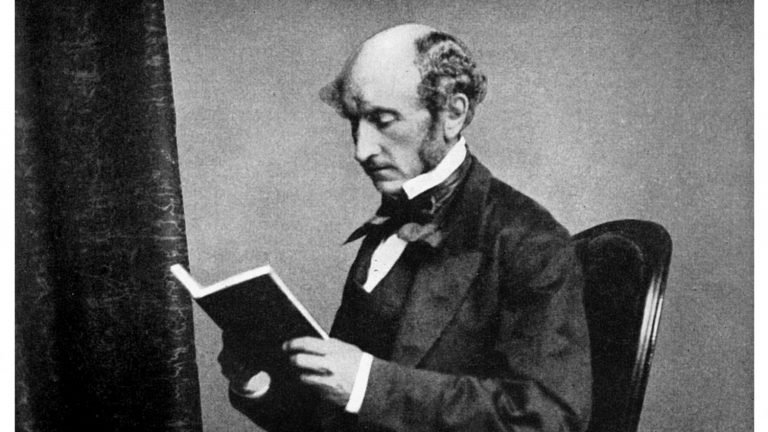

John Stuart Mill and the price of genius

Opinions differ, of course, about how best to enact this sort of concern for those who aren’t within our immediate community, but most cosmopolitans are overtly in favour of pluralism and conversations between people with widely different assumptions. In a world joined up by the internet, we are not only in this together, but we are literally connected with each other: we are in what Marshall McLuhan described as a global village.

Cosmopolitans, whether Christians or not, see ourselves as citizens of this global village, and that makes every other human being our fellow citizen, towards whom we have responsibilities, and obligations. But we also recognise that local practices, histories, and identities are part of what gives meaning to a life. We are entitled to live in very different ways from one another. We have biology in common, but our cultures and traditions are very different. Peaceful co-existence depends on recognising that.

Cynics in the modern sense may see any form of cosmopolitanism as colonialism in disguise, an attempt to export liberal values to the rest of the world, perhaps a mission to bring about a liberal world government, but that is a caricature. In 1955 Edward Steichen curated the Family of Man exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This consisted of a selection of the best photographs from across the world grouped in themes such as birth, family, work, death. It had a simple, optimistic, universalist message that annoyed some philosophical critics who thought that you couldn’t just assume a single human condition or human nature.

Both Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag, with some justification, accused Steichen of naive sentimentalism and of smoothing over the specificity of historically embedded ways of being. More sophisticated cosmopolitans, however, argue not for deep universalism like Steichen’s, but, more plausibly, that we have sufficient overlap in our biology, moral psychology and patterns of life to have the conversations and negotiations that are a pre-requisite for peaceful co-existence and flourishing.