You are in prison and two guards watch your every move, one on each side of you. They don’t leave you alone for a second, not when you use the shower or toilet, not when you’re sleeping. Privacy is just whatever interior thoughts you’re able to muster in that predicament.

Then, on your release, you are scrutinised via multiple cameras outside your house, guards control who comes in and out, your communications are monitored and restricted. Later, you find listening devices hidden inside electric sockets in your studio.

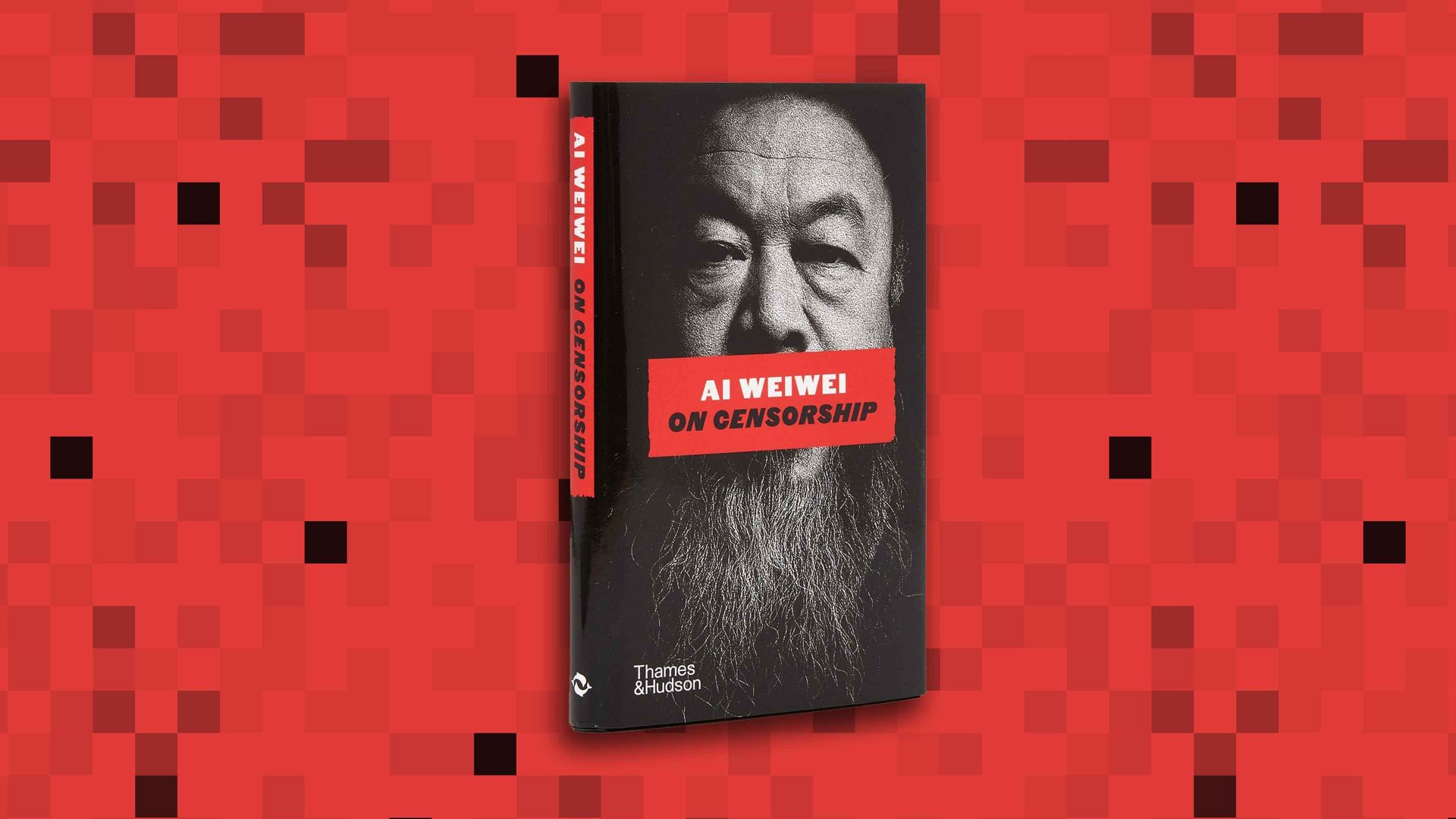

The artist Ai Weiwei has survived all this and more. He knows about authoritarian censorship, surveillance, intimidation and state control. It’s sometimes the subject of his art, when he turns what has been done to him back on the perpetrators, as for instance with “Ai Weiwei cam”, for which he installed four of his own cameras and streamed his own life online, another work that was swiftly censored.

Ai Weiwei has survived every attempt to break him and is stronger as a result. His bravery is extraordinary. So is his inventive capacity to engage in political dissent through his art.

Ai Weiwei challenges official narratives on social justice and abuses of authority. Like Socrates, he is driven by his conscience and a willingness to be the gadfly who irritates the state with awkward questions.

His international prominence has itself presented difficulties for the Chinese trying to control him because everything that happens to Ai Weiwei is visible to the wider world. He has been beaten, imprisoned, threatened, and his online presence systematically erased or distorted in China.

Since his investigation into why more than 5,000 children died in the Sichuan earthquake of 2008, he has been targeted repeatedly. The authorities interpret his demands for transparency of information as a political act.

You might then expect a book about free expression by him to be directed entirely at how authoritarian states stifle dissent, independence, and creativity. But his just-published 90-page tract On Censorship takes a different angle.

He stresses that this phenomenon isn’t restricted to autocracies. He writes of the “covert” and “diffuse” ways in which the expression of unorthodox views is censored even in “the so-called free world”.

Thought control, the essence of censorship, is usually motivated by the desire to maintain power, and can operate, he says, through the media, through releasing distorted information and lies, and through political and social forces as much as through intimidation by state police and the self-censorship that almost inevitably follows that. He cites the example of how even within the supposedly free society of the US, those who protested against Israel’s actions in Palestine were immediately labelled antisemitic, their stories not fully covered in the media, and some were incarcerated or deported.

There is a Chinese proverb, “kill the chicken to scare the monkey” – meaning to punish a single violator as a warning to the wider population. Ai Weiwei is saddened by how this tactic makes artists afraid, and can push them towards conformism and a loss of authenticity that ultimately proves antithetical to the aims of art, and of humanity.

Suggested Reading

Dr Bot will see you now

Censorship, he reminds us, is “the natural enemy of human thought and expression” (John Milton recognised this long ago when he wrote ‘he who destroys a good book kills reason itself’). Censorship distorts our intellectual, artistic, and social systems, “reducing them to values that serve only specific agendas or social frameworks.”

These are the strong messages of On Censorship, and they come close to John Stuart Mill’s 1859 liberal defence of extensive free expression On Liberty. Ai Weiwei’s fears about conformity arising from indirect censorship echo Mill’s concerns about “the tyranny of the majority” too, as do his claims about how censorship undermines social progress.

He adds fears about the impact of constant digital surveillance on independent thought, and deep concerns about the erosion of privacy as a result of technological developments. Unlike Mill, however, Ai Weiwei doesn’t discuss appropriate limits to expression, the difference between liberty and anything-goes licence, the point at which expressing an idea becomes an incitement to violence and so should rightly be curbed.

While On Censorship provides a useful prophylactic against western smugness about our allegedly open societies, and a warning to artists about the risks of conformity, it still leaves the hard problem of free expression unaddressed, namely, where should we draw the line?