Chairman Mao’s face was indistinct, hazed by the grey filthy air. There was a taste of sulphur on my tongue as I hailed a taxi to get out of Tiananmen Square, leaving his huge portrait behind. I was going to meet a friend who was taking me to the lesser-known temples of the city. We had set aside a full day for lacquered wood, pine trees, carved stone and Confucianism.

The taxi was new for 1995. It was a China-made Volkswagen Jetta, built to a 1980s design, with a build quality from the decade even before that. The sharp-edged doors made of biscuit-tin steel clanged when you shut them. Later, as my friend Wei Wei and I were walking through quiet courtyards, she explained that a large number of joint ventures were being set up in China with western car companies, the lure being access to the vast and growing Chinese market, and the cheap cost of manufacturing.

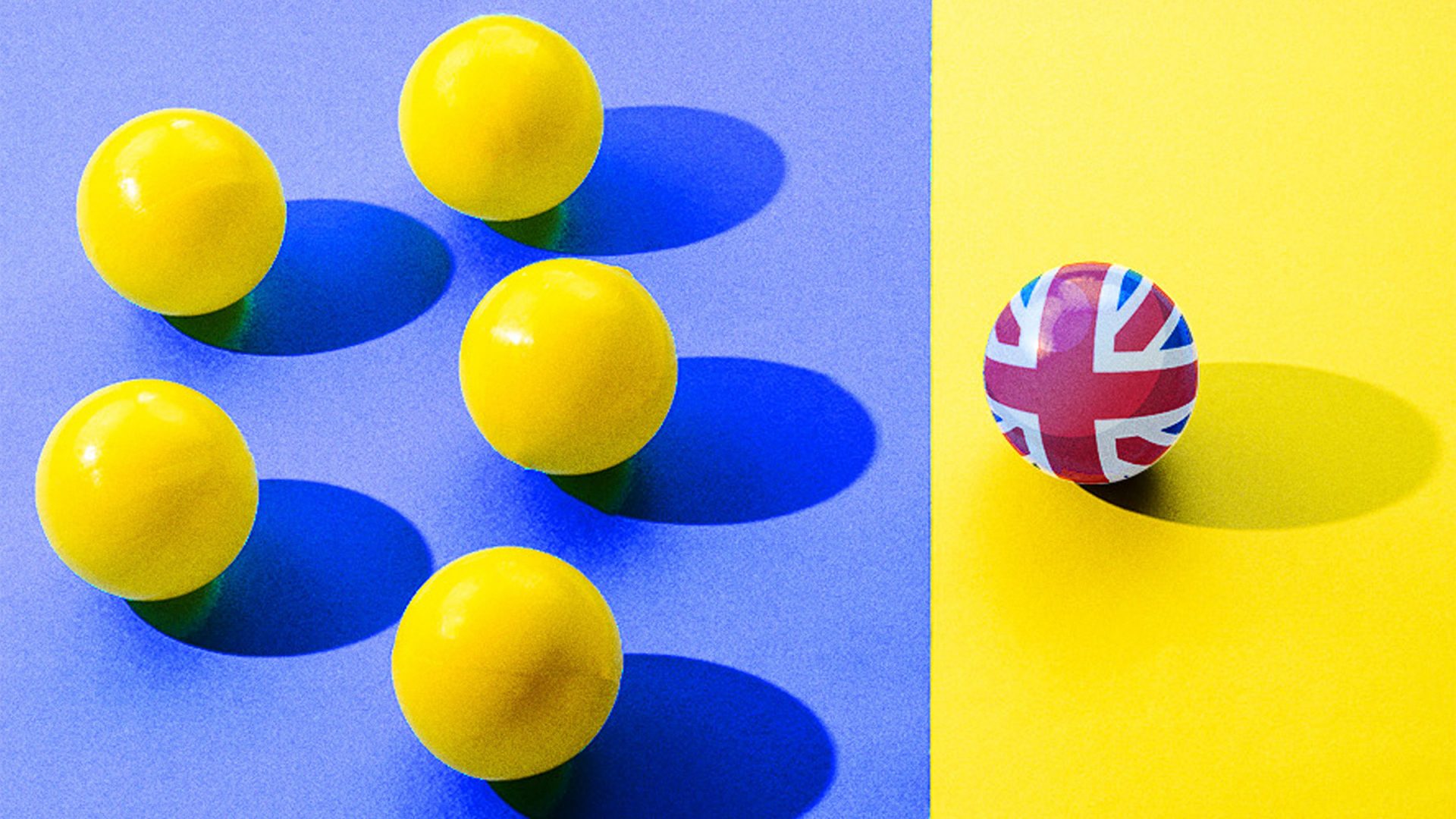

Three decades later, the boss of Ford, Jim Farley, took a test drive in one of the latest Chinese BYD electric cars, along with his chief financial officer. “Jim,” the CFO told his boss, “this is nothing like before. These guys are ahead of us.” And he was right. In just three short decades, China accelerated to the front of the global car industry. The Chinese maker BYD now sells more cars in Europe than Tesla. How did they do it?

It was Deng Xiaoping who, back in the 1980s, first acknowledged the mistakes of the Cultural Revolution. Part of his more open policy towards the world included efforts to get foreign firms into China, and he invited Peugeot, Citroën and Volkswagen to build factories alongside local businesses. This led to all those joint ventures my friend mentioned to me back in 1995, when the SAIC car company (formerly the Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation) teamed up with VW, and the Brilliance Auto Group, another huge Chinese manufacturer, paired up with BMW.

But the destiny of China’s electric vehicle industry was sealed by two decisions. The first was to include the search for new transport technology in China’s 2001 Five Year Plan. The second came in 2007, when Hu Jintao appointed a new minister of science and technology named Wan Gang. He was an unusual choice. For one thing, Wan was the first non-Communist Party member nominated to the Chinese cabinet in 35 years. He had also spent decades out of the country. Wan had taken his PhD at the Clausthall University of Technology in Germany, and then stayed in Germany for a decade as an engineer for Audi.

It was Wan who came to realise that China could not catch up with the internal combustion car companies of the west. Invited to address the State Council of China, Wan proposed a search for alternative types of fuel, to allow the country to take a lead in car manufacturing without increasing China’s reliance on oil. As a result of his insights, China poured around $30bn of public subsidies into the electric vehicle industry, and installed a colossal new charging infrastructure. Wan has been referred to as “the father of China’s electric car industry”.

The effects were gradual, at first. Wan oversaw the construction of a fleet of electric buses for Beijing, to ferry visitors around the city during the 2008 Olympic games. It happened to be the same year that Elon Musk became CEO of Tesla.

But then the effect of the state’s investment began to show itself. In 2009, China officially became the world’s biggest car market and the societal and economic changes started to accelerate. “Just look at Ningde,” a friend of mine from the industry told me, referring to the coastal city. “It was an impoverished county. Then CATL [the battery manufacturer] got $500m-plus in grants, cheap hydro-power and a dedicated rail line to Shanghai and the port. Now it’s Battery City.” (Xi Jinping was head of the communist party in Ningde from 1988-1990).

This extreme dynamism contrasted with the more staid strategy of the big car brands in the west, which kept on producing internal combustion-engine cars, while trying to conform to increasingly tight emissions regulations for a power system that was inherently inefficient and polluting. It was not that they were blind to the value of electric vehicles. After all, Mercedes invested $50m in Tesla in 2009, and Toyota bought $50m in shares after the initial public offering (IPO).

Suggested Reading

China’s AI game changer

But neither of them had the imagination or the will to look long term. Thus, Mercedes sold its shares in Tesla back in 2014, making a nice profit of $780m. But if it had held on to that stock for 10 years, Mercedes would have made $21.6bn.

At the time, Mercedes did not have to try too hard. It was a prestigious brand and China was quickly becoming its largest market: what could possibly go wrong? Andy Palmer, former global CEO of Nissan and the man who created the electric Nissan Leaf, knew exactly what could go wrong. “I’ve been warning about China for 15 years,” he said. “I warned the Japanese, UK and US governments that China might get this right. And, ultimately, that has proven to be the case.”

What he had seen was the rapid Chinese progress in understanding how to build a car, combined with Wan’s recognition that it was pointless trying to compete with the big, established brands. The Chinese manufacturers knew their cars had to be different. They simply circumvented the western competition.

They also realised that batteries offered even greater potential, as the technology had multiple applications, including home and grid energy storage, in power tools and even in powering drones. All they had to do was become the best in the world at making batteries. That would mean getting control over the supply of raw materials in order to block out the competition.

In doing all this, they had two things in their favour. First, implacable government determination. Second, they had lots of cash, thanks to a world trade surplus of $857bn a year.

A couple of years ago I was asked to help set up an assembly plant in the UK for Chinese electric vans. The aim was to sell the vehicles at half the price of a van from an established manufacturer. To pull that off, there would have to be huge savings on the battery cost. As one industry insider told me, the answer was resource control. “Chinese firms like BYD control mines in Chile, and CATL have cobalt from Congo,” they explained, describing the process of resource extraction as a kind of “state-capitalist orchestration”. It was, the person told me, “ruthless”.

There was another reason for China’s obsession with batteries. For the west, the issue of climate change is a moral imperative. But China has a desert to the north, poor soil, erratic rivers and a low-lying southern coast, which makes climate change an existential crisis. Add to this the need to import 73% of its oil and 42% of its gas, and there are clear advantages to being able to generate power domestically. This is why China installs more than 60% of the world’s total renewables every year. It is also why China’s CO2 emissions are now falling. Then, to store all that new clean energy so it can be used on demand, China uses its own batteries.

Even the self-styled visionary Elon Musk got it wrong. In 2011 he scoffed at one of his Chinese competitors, saying: “I don’t think they have a great product, I don’t think it’s particularly attractive, the technology is not very strong.” Just over a decade later, BYD was selling 4.27m cars a year, to Tesla’s 1.84m. And that was before Musk’s madness eviscerated the company.

Suggested Reading

Our media obsession with Trump is playing into China’s hands

Complacency is endemic in the automotive industry, but it is still shocking that it was not until 2024 that anyone thought it might be interesting to dismantle a BYD to see why it cost so little to make, and why it was so good. A group of western researchers who did found that the BYD Seagull was: “Efficiently and simplistically designed, engineered and executed, but with unexpected quality and anticipated reliability.”

What they could have added is that BYD is the most efficiently structured company in the world (its full name of “Build Your Dreams” being its vision). Alongside it are SAIC, which owns MG and Rover, and Geely, which owns Lotus, Polestar, Volvo as well as numerous Chinese brands. All these companies are now plugged, literally, into the government-controlled Chinese manufacturing system, with its iron grip on the necessary natural resources, and are sold to state-subsidised Chinese consumers, who now have a network of 2m public charging points to support them. Meanwhile, electric VWs clutter Chinese storage yards, unsold because they are less reliable and have inferior technology, even though they use Chinese-made CATL batteries.

Complacency allowed China to dominate battery manufacturing. But batteries are just dumb boxes without software, and this software must have an online connection for optimal performance. So, now we are arriving at a point where cars, home batteries and grid storage are controlled by Chinese companies, all of which are legally required to comply with instructions from the CCP.

That is increasingly the case across China. Might that also soon become the case in other countries – in nations across the west, even? What would it mean if Europeans came to rely on Chinese cars, powered by Chinese technology, all of it under Chinese control? It is a question worth asking because it is already happening. And they do, after all, make very good cars.

Nick Battersby is a photographer and technology developer