When West Germany’s first post-war chancellor, Konrad Adenauer declared that he wanted “specialists, not boy scouts” in his government he inadvertently gave voice to a disturbing conundrum. Disturbing because the only “specialists” to hand were those who had spent the previous decade running the machinery of Germany’s National Socialist government, waging war across Europe and exterminating swathes of people they regarded as inferior.

But surely such people were no longer around, ready to settle in behind a desk and help to build a new West German state from the ashes of the one they’d so recently brought to ruin? A pity for Adenauer, but weren’t they all behind bars?

Eighty years ago this month, in Courtroom 600 of the Palace of Justice, the Nuremberg trials began. Twenty-one high-ranking figures in the Nazi government and associated organisations stood trial before an international military tribunal. They included commander of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring; foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop and minister of the interior, Wilhelm Frick. At its conclusion 11 were sentenced to death, seven received prison sentences and three were acquitted.

Later, 142 more leading Nazi officials were convicted in subsequent trials in Courtroom 600. By October the following year the trials were over.

They were a significant milestone, establishing the guilt of both state and individuals complicit in war crimes and genocide. Today they are considered the precursor to the establishment of the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

The Nuremberg trials resulted in only 160 convictions. Yet, beforehand, the Allies had identified almost 2500 leading Nazis whom they considered should face justice. So, what happened? Why were there so few successful prosecutions?

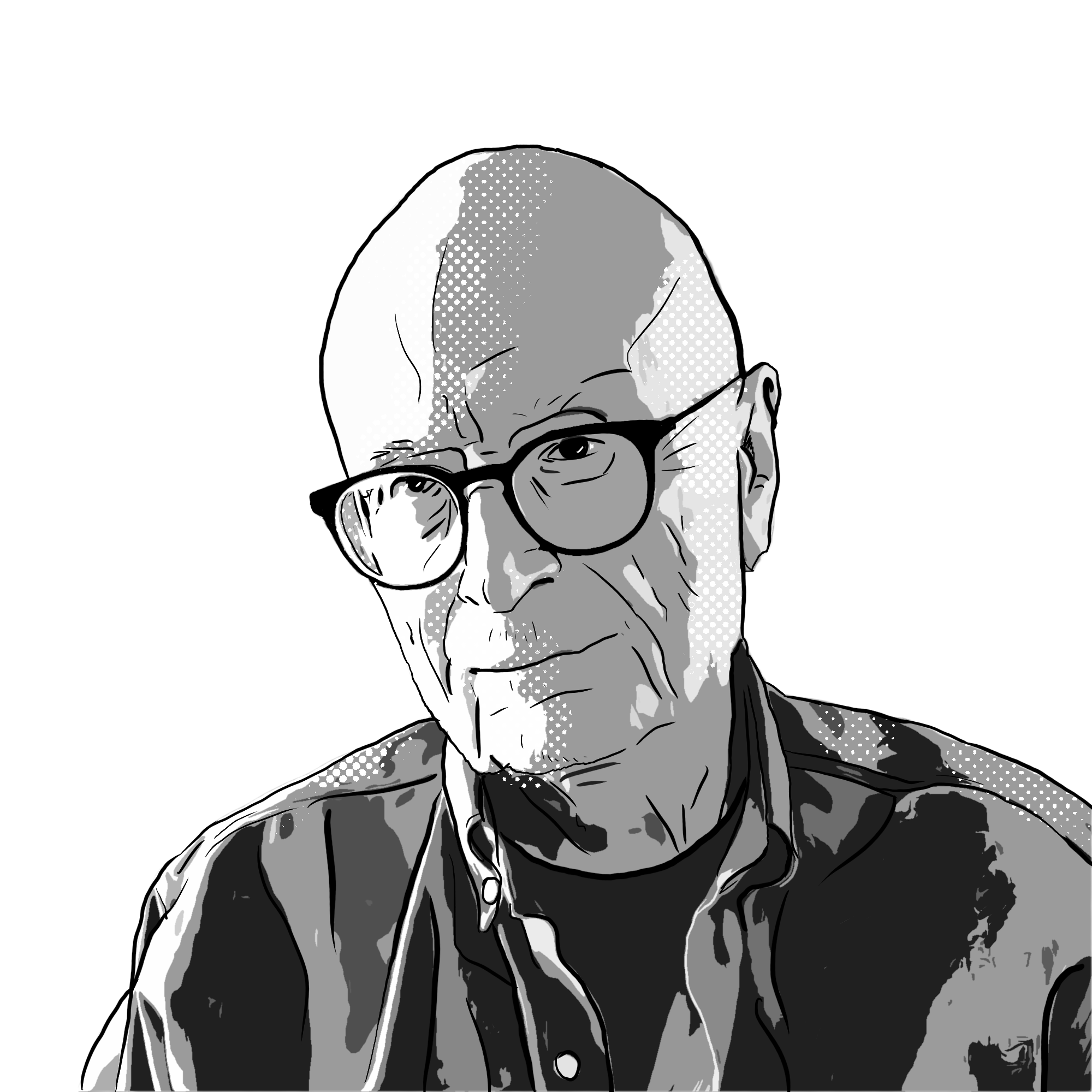

“Actually, the figure is far higher than that,” says Axel Fischer, research associate at the Nuremberg Trials Memorium archive. “It’s estimated that there were around 2 million potential perpetrators of Nazi war crimes ranging from relatively minor all the way to genocide.”

And therein lies the problem. “The most prominent faced justice, but it is unfeasible to try so many people. For a start there aren’t enough courts, lawyers or prisons,” explains Fischer. “There were other trials in standard German courts and other European countries, but in total there were fewer than 7000 convictions and some sentences were notably light.”

All of which meant that by the 1950s, West German society was once more being organised by people who had been prominent in the Nazi regime. They re-entered public life, be it in government (Adenauer’s “specialists”), the judiciary or business.

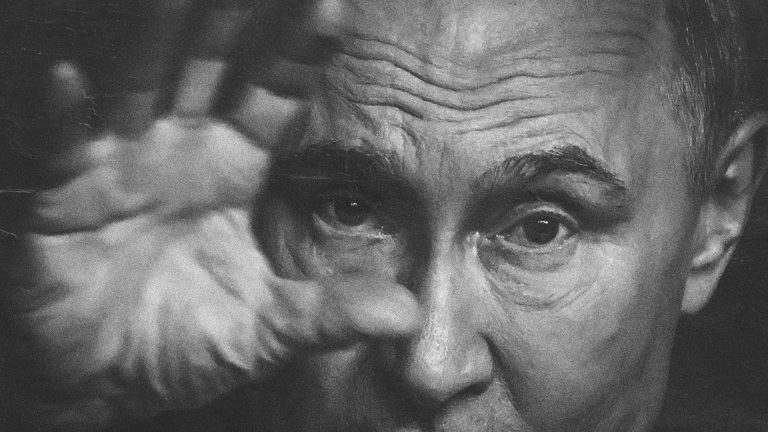

They were people such as Hans Globke, who in 1953 became chief of staff to Adenauer. Originally a lawyer, Globke had helped draft the Nuremberg Race Laws passed by the Nazis in 1935 which codified antisemitic legislation. Of all the Nazi affiliates who continued in government in post-war Germany perhaps he is the most prominent example.

But there were many others. Ernst Achenbach was a diplomat in Nazi-occupied France who helped co-ordinate the deportation of Jews to concentration camps. Not only did he later serve as a member of the Bundestag between 1957 and 1976, he was a member of the European Parliament from 1964 to 1977, ironically president of the parliament’s Liberal grouping.

Even West Germany’s third chancellor, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, had form. He had worked in the Nazi Party’s foreign office propaganda department.

Although there was no evidence linking him to specific crimes his chancellorship was not uncontroversial. Most famously he was confronted at the 1968 Christian Democratic Union party conference by Nazi-hunting journalist Beate Klarsfeld who climbed onto the stage shouting “Nazi, Nazi, Nazi” and then slapped him across the face.

How did former Nazis rise again, so quickly? It was a rather unholy mix of both expedience and pragmatism. “When the Central Office of the State Justice Administration was established in 1958 in Ludwigsburg to co-ordinate the investigation of crimes the Nazis committed against the people of their own country, it realised the task was impossible,” says Fischer. “You cannot try 2 million people. Society would simply break down. So they prioritised the worst. Distasteful but pragmatic.”

And thus, Adenauer got his low-ranking Nazi government officials. “He needed their experience so West Germany could function,” adds Fischer.

All walks of life, not just government, were affected. Hermann Josef Abs was a leading financier at Deutsche Bank during the Nazi era. The bank underwrote Nazi industrial projects and took part in the aryanisation of Jewish businesses.

After the war, somewhat ironically, Abs became a key figure in the instigation of the United States-backed Marshall plan to regenerate Germany.

Perhaps more disturbingly, Carl Wurster – who although arrested avoided prosecution – was an executive at IG Farben, the company which produced Zyklon B gas used to exterminate Jews at Auschwitz and elsewhere. He became chair of BASF and was instrumental in reviving West Germany’s chemical industry.

Suggested Reading

The urgent and dramatic power of Nuremberg

Even those who were convicted returned to public life. Friedrich Flick was one of the wealthiest industrialists in Nazi Germany. His businesses used forced labour and profited from property stolen from Jews.

He was sentenced to seven years for crimes against humanity. But after release he rebuilt his industrial empire and by the 1960s was regarded as West Germany’s richest man.

Meanwhile Alfried Krupp was head of his father’s armaments and steel empire which used concentration camp inmates. His father, Gustav, was considered too ill to stand trial at Nuremberg, but Alfried was later tried and sentenced to 12 years.

However, Germany needed his business acumen and, under pressure from the US, released him in 1951. He played a leading role in rebuilding Germany’s heavy industry.

Other former Nazis were spared because they were useful to the Allies. Prominent examples include Wernher von Braun the inventor of the V2 rocket used to attack London and Paris, who went on to play a vital role for NASA in the US space programme, and Hubertus Strughold, an aviation clinical researcher; linked to experiments on prisoners, who became a prominent aerospace medical expert, honoured by NASA.

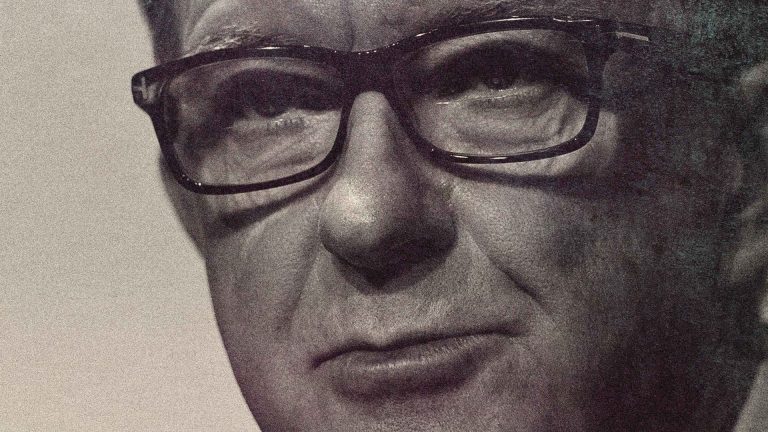

But there were others. Reinhard Gehlen had been head of Wehrmacht intelligence for the Eastern Front, fighting the Soviet Red Army. Although he was captured by the US they realised they could use his expertise against the Soviets so he evaded prosecution, becoming head of the BND, West Germany’s foreign intelligence service, from 1956 to 1968.

The whole process of denazification and rehabilitation of former party officials became known as Persilschein, a combination of the words “Persil”, named after the laundry detergent manufacturer based in Düsseldorf, and “Schein” or “certificate”.

Following the war, all German adults were given questionnaires asking them what involvement they had with the Nazi regime. Unsurprisingly, very few admitted collusion and so they received a certificate to say they had been denazified or “washed clean” even though many were indeed complicit.

So, what did the average German think about the situation? Having been put through six years of war and the destruction and partition of their country, how did they feel about the perpetrators resuming positions of influence?

Volker Straub from Hamburg, now 80, was born just as the war ended. He became politically aware while Kiesinger was chancellor between 1966 and 1969.

“Once I learned what my nation had inflicted on the world, I was astonished to discover that some of the culprits were free and in important positions. But I’m more sanguine now.

“It was wrong, absolutely wrong, but the nation was in turmoil, we had to have stability and, now, truthfully, I feel it helped turn Germany into the democracy it is today.”

For Fischer, “Rightly or wrongly, it was realpolitik. If, during the war, you saw men in striped pyjamas working in a factory you knew the owner had been using forced labour.

“Some people were appalled but mostly they knew full well why they weren’t being prosecuted. Some were angry, others ignored it or turned a blind eye.”

But did turning a blind eye sometimes lead to violent retribution? German terrorist organisations such as the Baader-Meinhof Gang waged war throughout the 1970s and 1980s against what they perceived as a bourgeois society propping up a fascist establishment which contained former Nazis.

“In part, yes,” says Fischer. “Certainly, the kidnap and assassination of Hans Martin Schleyer had overtones of this.” Schleyer had been an SS officer but had reinvented himself as a business leader. He was killed by Baader-Meinhof in 1977.

“But Baader-Meinhof would probably have happened without former Nazis returning to government,” explains Fischer. “It was just one factor among many: the Vietnam war, capitalism, Cuba… they all played their role.”

And were any of the former Nazis now back in prominent roles ever contrite or remorseful? “No,” says Fischer bluntly.

Suggested Reading

The urgent and dramatic power of Nuremberg

“For example, Franz Josef Strauss, president of Bavaria until 1988 and previously an oberleutnant in the Wehrmacht, visited veterans of the German campaign in Greece every year and held celebrations with them. Terrible atrocities were committed in that campaign, but he showed no remorse. He even wrote a letter to former Waffen-SS members telling them how much he admired them. It was shameless.”

So, 80 years on, are the Nuremberg trials seen as a fig-leaf, a veil through which the highest-ranking Nazis could be seen to be prosecuted but which allowed the majority of those complicit in the regime to hide from justice while giving the Allies their slice of retribution? Or were they a worthy attempt to bring restitution and closure to one of humanity’s darkest eras?

“You have to separate out the two,” says Fischer. “Allowing Nazis back into public life was pragmatic necessity. Not only the West German government but also the occupying Allied forces prioritised economic stability and anti-communism over justice, especially after the Soviet Union effectively annexed East Germany and instigated the blockade of Berlin.

“But of the trials themselves, most historians would now say that, despite their limited scope, they were a great accomplishment. They laid out principles for modern international criminal law that are still adhered to today.” Fischer is speaking in Courtroom 600: “We are still proud here of what the trials represent,” he says. “They shaped ideas that are still relevant and were a genuine attempt to bring about peace and a form of reconciliation and to stop such things happening again.

“They also made it more difficult for those involved in the crimes to say ‘oh, it was just a period in German history’. Ex-soldiers often argued they simply acted like other armies of the past. But because of the huge amount of evidence the trials had collected it could be proved that this was untrue, they did act in terrible ways.

“We have verifiable documentation. And this, I think, is the most vital legacy of the trials, not so much the limited, but important, prosecutions. The trials made it impossible to deny the facts even if justice, in many cases, was not always served.”