“Is that supposed to happen?” asked an apprehensive member of the crowd gathered in Florida to watch the launch of the space shuttle Challenger. She was right to be concerned. It wasn’t meant to happen.

When the orbiter broke apart 73 seconds after departing Cape Canaveral on January 28, 1986, in so many ways it marked the end of the space race, an era bookmarked by the launch of Sputnik I in 1957 – the first human-made object to orbit the Earth – and the Shuttle’s obliteration. An era when the ideology and technical acumen of the Soviet Union and the United States battled for supremacy beyond Earth.

Perhaps even more significantly, it marked the end of an age of innocence when Americans, and indeed the rest of the world, had started to view spaceflight as a safe, almost everyday occurrence. NASA had never lost an astronaut in space. Strictly speaking, the administration would still say it never has – Challenger was within the Earth’s atmosphere when it exploded – but to a shocked, watching world, that was of little consequence.

And it was intended to be a particularly special flight. Much had been made beforehand about the first American civilian (bar two Congressmen) to fly in space.

In 1984, US president Ronald Reagan had announced the Teacher in Space project to find an educator, “an ordinary member of the public”, who could communicate with students while aboard the shuttle. Christa McAuliffe, a social studies teacher from New Hampshire, was chosen from more than 11,000 applicants. She had appeared on numerous prime-time television shows, her face was on the covers of magazines and newspapers worldwide and her launch aboard Challenger was to be broadcast live to schools across the nation.

The day dawned bright and sunny for the 25th space shuttle flight, and Challenger’s 10th. Aboard were commander Dick Scobee, pilot Michael Smith, alongside Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, Ronald McNair, Gregory Jarvis and McAuliffe.

However, despite the clear skies, the air temperature at the launch time of 11.38am EST was only 2° Celsius. Shortly after lift-off, puffs of grey smoke were seen emanating from the right-hand rocket booster. The icy conditions had stiffened one of the booster’s O-ring seals which failed, allowing pressurised gas to breach a fuel tank.

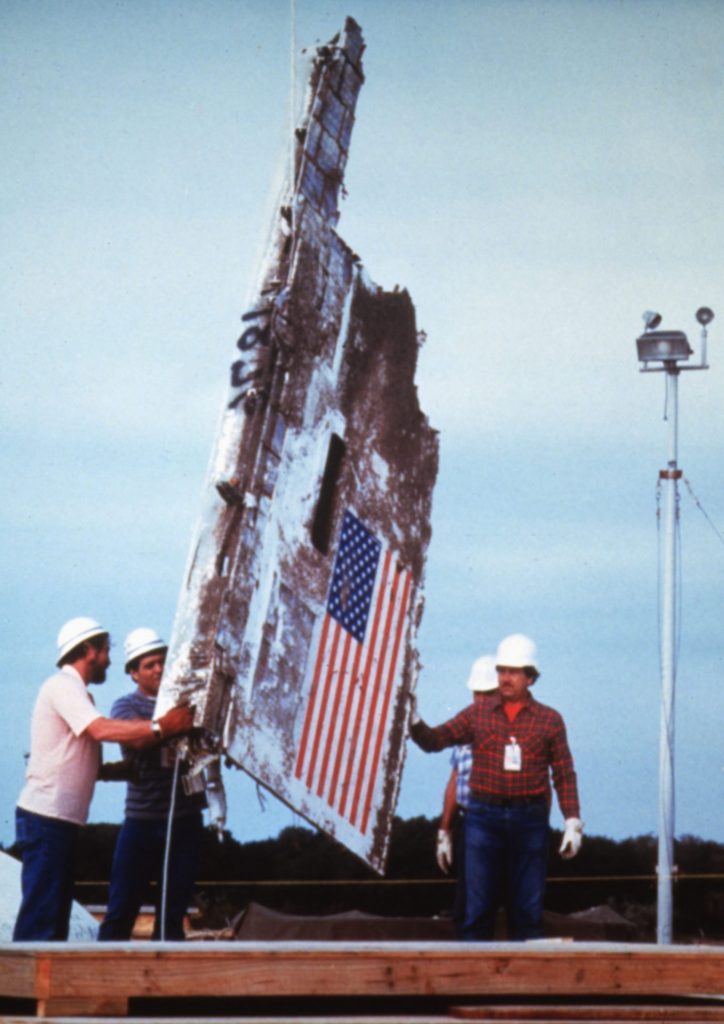

Just over a minute later, as mission control instructed Scobee to increase power, a plume could be seen coming from the tank. Smith’s utterance of “uh-oh” was the last communication from the shuttle. Travelling at Mach 1.92, it broke into pieces, plummeting into the Atlantic from where its remains, and those of its crew, would be recovered three months later.

Shuttle flights were suspended for 32 months while the enquiry was conducted. The Rogers Commission concluded technical failure caused the explosion but, more significantly, it questioned NASA’s safety culture.

The pressure to launch had been huge. The shuttle programme was running behind schedule and NASA was keen to see a teacher in space, believing the publicity would be significant for an administration constantly facing funding restrictions.

But, of greater import, it transpired that the temperature risk regarding the O-ring seals had already been flagged up. However, communication failures and pressure from management had overridden the concerns. And, consequently, this culmination of NASA inertia and directional oversight had played out live, and very tragically, on TV.

Suggested Reading

Ham, the chimp that launched the space age

Public trust in NASA, and space travel in general, was shaken. Although shuttles would fly again, the Challenger disaster transformed spaceflight from a symbol of routine progress into a reminder of its inherent peril. It was obvious that lessons needed to be learnt about leadership, communication, accountability and the human cost of ignoring warnings in high-risk systems.

Yet, underpinning everything, it was McAuliffe that resonated most with the wider public. “Her death is particularly painful because her voyage showed that plain folks can become heroes too,” wrote New Scientist magazine.

“Astronauts are targets onto which many ordinary people imprint their ideals. That one should be a smiling, New Hampshire schoolteacher means NASA will be under immense pressure to protect those it chooses to send into space. It may choose never to send a civilian again, nor perhaps any flesh and blood when robots could do the job equally well.” It chose the opposite, but the soul-searching was punishing.

Somebody who was not a career astronaut had been drawn into the tragedy. The media made much of the fact that McAuliffe had two young children with her teenage-sweetheart husband. She was, in so many ways, the perfect American mom. And now she was dead. The nation grieved.

“It wasn’t so much that she was a woman – Judy Resnik also lost her life,” says Emily Margolis, curator of women’s history for Washington DC’s Air and Space Museum. “It was because she was going to be America’s teacher in space. Inspiring kids across the nation.”

Plans to fly civilians in space were quickly mothballed. It would take 21 years before another teacher, Barbara Morgan – ironically she had originally been McAuliffe’s backup – flew aboard Endeavour, the shuttle that replaced Challenger.

Yet it’s debatable whether the changes undertaken at NASA in the wake of Challenger were ever truly implemented, or whether they merely papered over irremediable cracks in the culture of the administration. Seventeen years later, on February 1, 2003, after insulating foam broke free and damaged protective thermal tiles, a second shuttle, Columbia, broke up while re-entering Earth’s atmosphere, again killing all seven astronauts.

The independent Columbia Accident Investigation Board had this to say: “At NASA there were systemic organisational failures, including a culture of complacency, ineffective leadership, and missed opportunities to assess damage from foam strikes, which ultimately led to the loss of the crew. The administration prioritised schedule over safety and failed to learn from past incidents, including the Challenger disaster of 1986.” The reaction of the public to Christa McAuliffe’s death, it seemed, had not been heeded.

Mick O’Hare is a journalist whose specialisms include spaceflight. He was formerly an editor at New Scientist