Btyond Vladimir Putin, beyond Moscow – beyond Russia, even – there is Siberia. The Russian colonisation of the vast landmass of north Asia began in 1582, after the fall of the Khanate of Sibir, formerly part of the Mongol empire. Ever since, the vast region of north Asian tundra that reaches all the way from the Urals to the Pacific – and to China – has been ruled by Moscow. But now Beijing is showing an increasing interest in the resources that Siberia has to offer: resources that China lacks. The consequences of that could be far-reaching – perhaps even disastrous.

Russian settlers gradually moved into the vast wilderness, but in the 19th century prominent Russians like Dostoevsky and some 800,000 others ended up in Siberia as prisoners in internal exile. Stalin took this punitive practice to new levels in his archipelago of concentration camps known as the Gulag – masterly described by Varlam Shalamov in his Kolyma Tales. The vast icy wastes of Siberia had become an open prison.

But alongside this sinister reputation, another view of Russia’s great eastern wilderness has emerged. Over the last century, the immense natural riches of Siberia have inspired visions among Soviet scholars about Siberia and Dal’nyi Vostok (its Pacific coastal region) as a place of plenty and the key to Russia’s radiant future.

The Trans-Siberian Railway, completed in 1916, first opened the Russian mind to the enormous natural resources of the far east, including reserves of oil and gas, as well as gold, diamonds, manganese, lead, zinc, nickel, cobalt, molybdenum and rare earth metals.

Siberia came to be seen as a place that contained all of the necessary materials to build a nation of global ambition and reach. The trouble is, that’s how China sees it too. That collision of interests between Moscow and Beijing now has the potential to lead the two into direct confrontation over Siberia, with consequences for both nations, and also the world.

Siberia is not quite Russia. Its long history of close relations with northern and east Asia, and its adherence to shamanism make it culturally far removed from Moscow. That separate identity is a live political issue: in 2020, Siberians took to the streets in the city of Khabarovsk in support of their governor, Sergei Furgal, whom Putin wanted to replace.

Siberian oblastnichestvo (regionalism) expressed itself even more dramatically in February 2023, when Siberians held an unofficial online referendum on independence, and according to the Center for Countering Disinformation, 63.9% voted in favour of separating from Moscow. That vote was a reflection of a long-standing feeling that emerged during the Soviet period and has persisted ever since – that the people of Siberia and Russia’s far east have been ignored and that Moscow’s agenda is not beneficial for locals.

The advent of global warming has intensified the region’s political challenges. At the start of the 20th century, 65% of Siberia was covered by permafrost, but that figure is now down to 45%. Permafrost is a huge store of methane, a greenhouse gas 22 times more powerful than carbon dioxide. As the ground thaws, the methane is released.

But the Kremlin pays little attention to the climate time bomb of melting permafrost and methane gas emissions. And besides, Siberia is sparsely populated, particularly in the high north, which means there are very few people to witness this colossal ecological shift.

The callous attitude of the Kremlin towards its escalating climate crisis inspired the Finnish analyst Veli-Pekka Tynkkynen to portray the Kremlin as trapped in a “hydrocarbon culture” of climate denial. In his book Russia Against Modernity, Russian historian Alexander Etkind even suggests that Putin’s war against Ukraine is nothing short of a proxy war against the global green transformation.

Unlike almost all other governments, the Kremlin sees global warming as an economic opportunity. The melting ice in the Arctic Ocean will open the northern passage to shipping, allowing much shorter journeys from the Russian west to the Pacific east coast. This will have consequences not only for trade, but also for Russia’s naval manoeuvrability.

Suggested Reading

The next India-China war

The first container ship sailing from Russia’s far east to St Petersburg without passing through the Suez Canal on its route from Asia to Europe was the Venta Mærsk, which made the passage in 2018. But the surge in Arctic shipping has so far not materialised. In 2024, only 3m tonnes of cargo passed through the northern sea route, whereas billions of tonnes of cargo still go through the Suez Canal.

Even so, as the north thaws even more, and the need for icebreakers reduces, the shipping lanes across the Arctic will become more popular. If Russia comes to be seen as a more reliable geopolitical presence, the northern route could become more popular still.

Thawed ground may also allow for the intensified extraction of oil and gas. As the line of permafrost recedes northwards in Siberia, there is the possibility of a new Russian agricultural bonanza as new cultivable lands become available in place of the frozen tundra.

This, at least, is the Kremlin’s hope. But Thane Gustafson, professor of political science at Georgetown University and author of the widely acclaimed book KLIMAT: Russia in the Age of Climate Change, is less convinced that Siberia will become a new north Asian breadbasket.

“As one moves out of the present agricultural area,” he wrote in a 2022 research paper, “soils are generally poorer, thinner, and more acidic. To the north and east, even though permafrost will melt, the resulting exposed soil is infertile. “Permafrost is actually not soil,” he wrote. “There is no potential for expansion of agricultural land”.

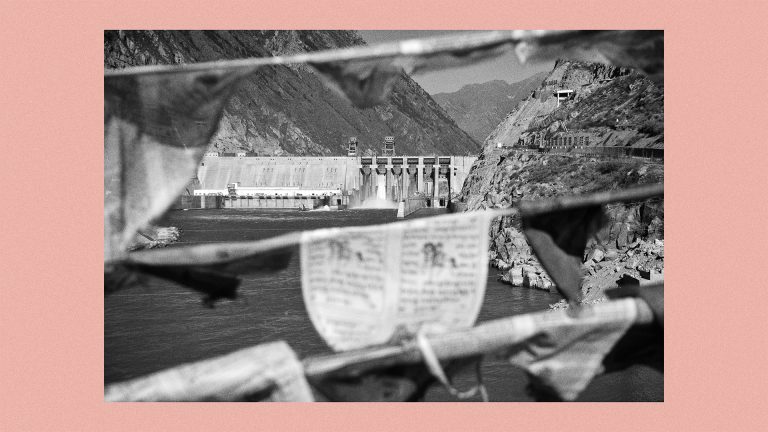

Watching all of the changes taking place in Russia’s far east is China, with which Siberia shares a 4,000km border. In theory, there is a harmony between the two powers: their economies are in balance and Russia has the huge volume of natural resources that China needs. What’s more, the Ukraine war has brought Putin and Xi Jinping much closer together in terms of their geopolitical outlook and military cooperation. The gas pipeline Power of Siberia has been supplying China with Siberian natural gas since 2019.

It has not been entirely harmonious. Negotiations over the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline ran into difficulty over questions of pricing and ownership. But the recent threat by Iran to close the Straits of Hormuz, after Israeli missile strikes on Tehran, may encourage Xi to look at Power of Siberia 2 as a valuable insurance policy. China depends on Iranian oil.

So far at least, China has tended to sit on the fence when it comes to its economic involvement in Siberia. Its ambitious Silk Road project concentrates on Central Asia, not Russia, and its investments favour Central Asia over Russia, albeit with an uptick since Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine began.

But China does not need to concentrate its efforts on Russia’s far east because its influence is spreading there already. Many young Russians now learn Mandarin, recognising where their future economic prospects lie. Chinese cars are a common sight on Russian streets (although BMWs remain the preferred choice). Perhaps the clearest sign of China’s growing cultural presence and influence in Russia is that the FSB is becoming ever-more suspicious of China’s intentions. They are afraid of a Chinese cultural and economic conquest by stealth, one that feeds on the ingrained Siberian dissatisfaction with the region’s treatment by Moscow.

But beyond this, there lies another far more unsettling possibility, proposed recently by the western analyst John Lonergan – an idea that has haunted conversations about Russia and China in recent years, and that probably looms large in the minds of Russia’s FSB leadership. Writing in the US publication The Hill earlier in the summer, Lonergan predicted: “China will invade Siberia, not Taiwan”.

His rationale for this stark pronouncement was that conquering Siberia would be much less risky and far more geo-economically rewarding for China than going after Taiwan. On top of direct access to Siberia’s vast fossil fuel and mineral reserves, the uniquely deep freshwater reservoir of Lake Baikal offers the answer to China’s chronic and worsening water scarcity problem.

As Lonergan also points out, the weakening of Russia’s military muscle from its crippling war against Ukraine may also influence Xi’s calculus. His prediction disregards the nuclear balance of terror between China and Russia, but even so it remains an outcome that cannot be excluded.

It will become an even greater risk for the Kremlin if Putin’s hubris leads him to open a full-scale war against Europe and Nato. Putin and Xi seem to cherish their illiberal “partnership with no limits”, and most analysts expect China to simply slowly profit from Russia’s self-harming conduct. But the prospect of Siberian riches may one day tempt China to strike Russia in the back.

Mette Skak is emerita associate professor at Aarhus University