The idea of humanoid robots as part of the inevitable sci-fi future has been sold to us since the 1950s, by future-gazing authors, film-makers and, latterly, awful billionaires and venture capitalists with dust where their souls should be. Despite the hype, though, the prospect of a life alongside a bipedal plastic pal who’s fun to be with has largely seemed the stuff of filmic fantasy… but that might change sooner than you think.

What, do you think, is the going rate for a programmable humanoid robot, shipped straight to your home from Hangzhou? How does £4,500 sound? For less than the price of a month’s London rent, you too could be the proud owner of a Unitree R1, a 1.2m tall, fully articulated robotic device equipped with cameras and speakers and LLM integration, ready to be programmed to do whatever you want it to.

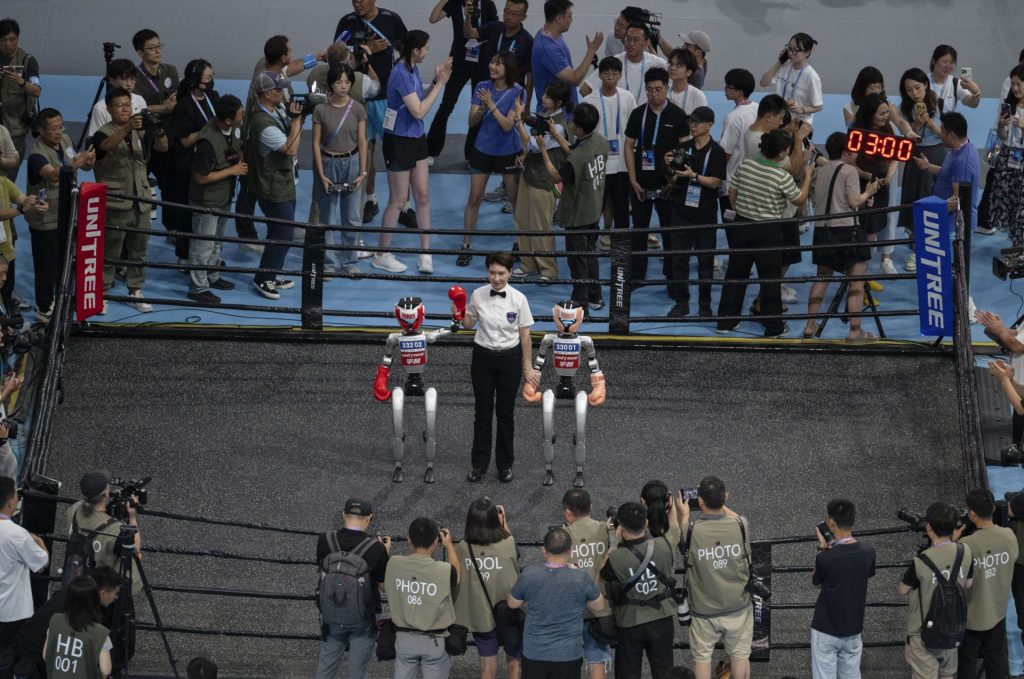

Well, within reason – the promotional videos on the company’s website are full of footage of the R1 running and jumping and performing handstands and acrobatic somersaults, but there’s less evidence that it can do anything practically useful. This is, perhaps, exacerbated by its lack of actual hands – the base model instead comes equipped with what can only be described as bludgeoning tools, demonstrated in frankly terrifying footage of it shadowboxing at a clip that would give even Tyson Fury pause.

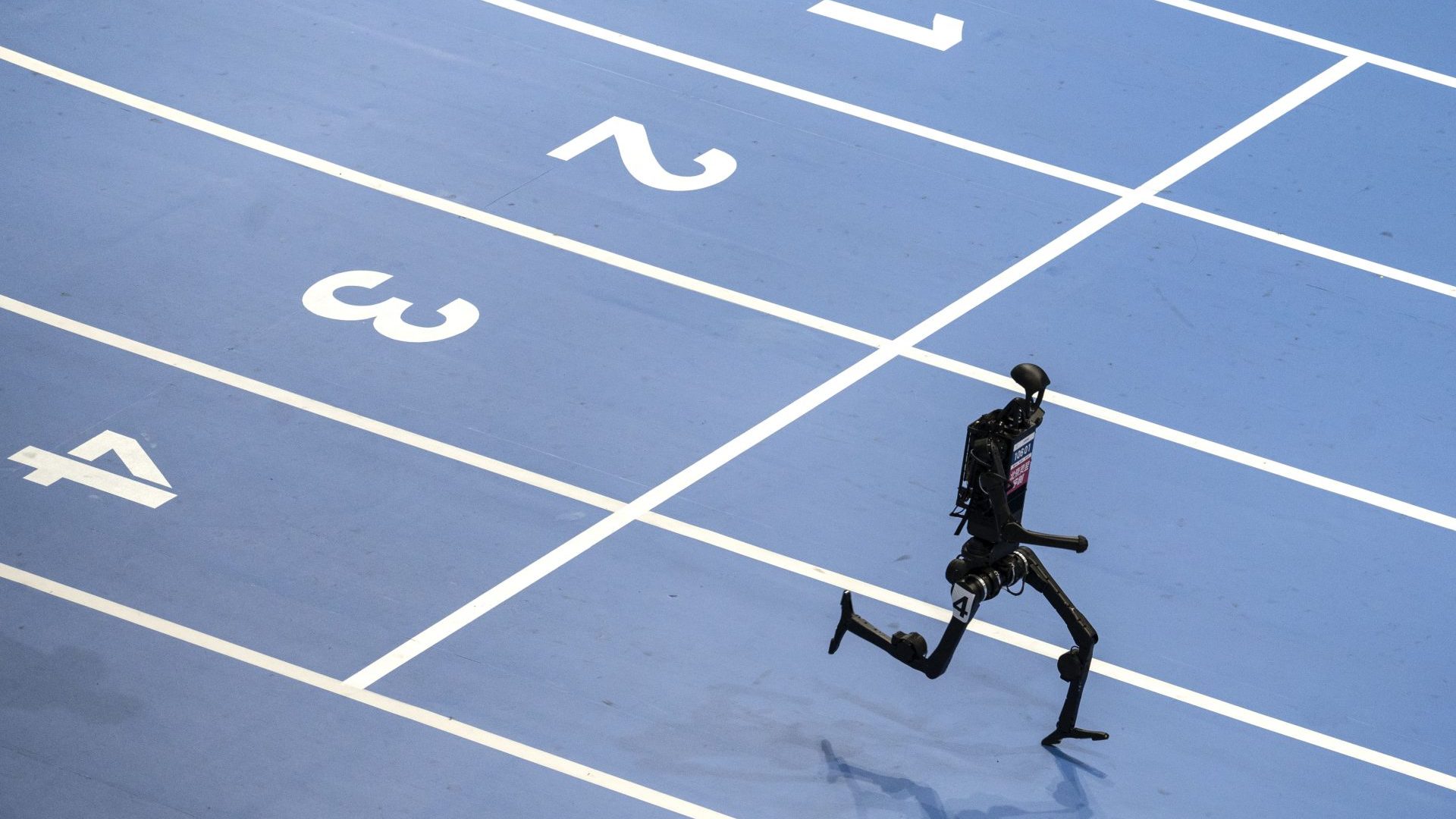

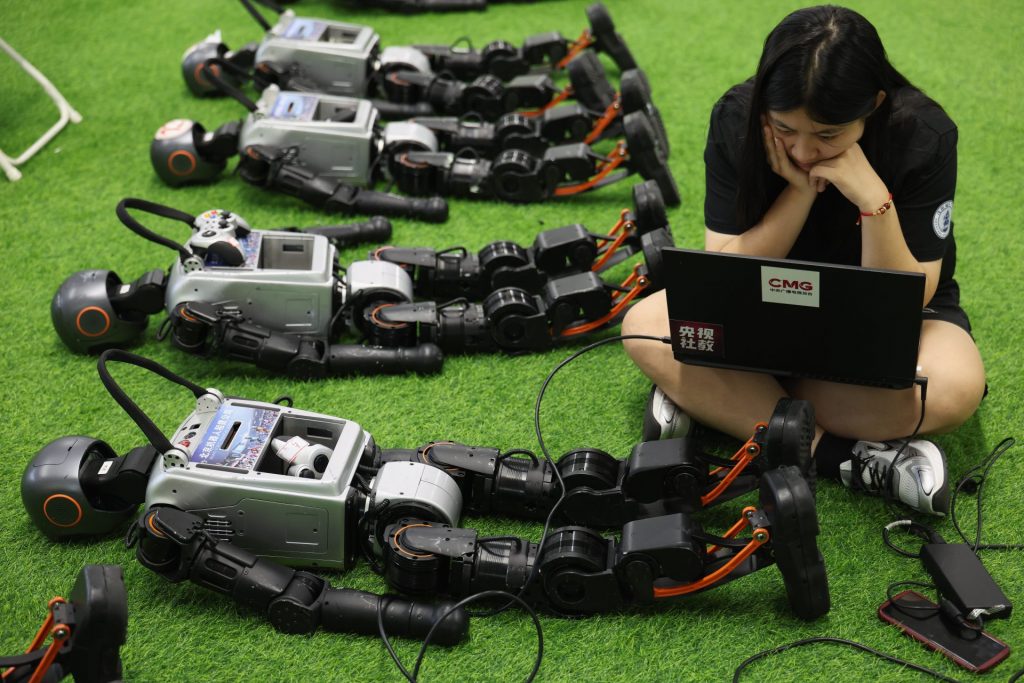

Last week saw Unitree robots take part at the 2025 World Humanoid Robot Games in Beijing. A total of 280 teams from 16 countries across five continents represented. Robot Wars, this wasn’t.

The world’s first fully autonomous 5v5 humanoid robot football match was hardly Premier League standard either, but it was a step up on the 3v3 games staged at previous events. The artificial intelligence-powered robots positioned themselves correctly from the kick-off and played two 10-minute halves, picking themselves up when they got knocked down in collisions. None dived to win a penalty, or went on strike, Alexander Isak-style.

Meanwhile, over in Texas, Elon Musk’s latest outlandish pitch to Tesla shareholders is that the company will produce 10,000 of its “Optimus” line of humanoid robots by the end of 2025, with the billionaire predicting a fleet of 10 billion of the devices in existence as the market matures (Musk has also been predicting full self-driving capabilities in Tesla cars since 2016, though, so some scepticism is advisable).

competitors during the 5v5

football preliminaries

We have for several years now become used to the occasional video of dog-like Boston Dynamics robots capering on factory floors, or its larger models doing backflips, but the past 36 months has seen an uptick in the speed of development and deployment of contraptions that look a little more like the sort of thing imagined by Douglas Adams and others in the 20th century. How come?

As with so much of this, the answer is in part “generative AI”. The development of multimodal AI models – that is, ones which can process inputs in multiple formats, including video and audio – has radically shifted the needle. In the past, multimodality in AI often involved separate models for different types of data (text, image, audio) with complex integration processes – a problem in creating low-cost, mobile robotic systems.

Now, though, multimodality has become more integrated, allowing a single model to process and understand multiple data types simultaneously, improving the efficiency and effectiveness of AI applications and making their integration into robotics systems significantly easier and more effective.

It’s not just what’s inside the robots. LLMs have also enabled significant advances in the development of simulation models, allowing for the pre-training of machines within simulated environments that mimic the real world. Google recently announced a state-of-the-art new “world model” called Genie3 which can be used to create digital mock-ups of any environment one chooses to imagine, mock-ups which can be virtually “explored” to create training data which is then used to improve and optimise the performance of robots in meatspace.

It’s all part of the continuing race to develop AGI –artificial general intelligence – or whatever they’re calling it this week. There’s a growing branch of thought within the AI community that there may be certain inherent limitations within LLMs that will prove a fundamental barrier to taking the next, potentially decisive, step towards better-than-human performance by machine intelligence – and that those limitations will require robotics to overcome.

The problem, put simply, is one of embodiment, and the question of whether “human-level” intelligence and a truly agile virtual mind, is dependent on “embodiment” – having a concept of the world, the intelligence’s place within it, and the effect of real-world forces and stimuli on both the agent and the environment. If this experience is essential to crossing the AGI rubicon, it will require huge quantities of sensory data that in some way mimics the human experience of existing in physical space.

Robots equipped with cameras and microphones and tens of thousands of sensors, all gathering data to feed back to centralised systems for processing and analysis, are increasingly looking like the best way to achieve this at scale.

Exactly how quickly this all comes to pass is, of course, unknown – and there’s no guarantee that solving the problem of embodiment will get us any closer to the promised lands of AGI (or indeed that we even want to get closer). Regardless, though, it’s clear that there’s a significant amount of money riding on being at the forefront of the race to get there, and that robots are going to be a big part of that.

Remember that next year, when the bagging assistant at Lidl has been replaced by an Optimus, hoovering up data to eventually feed the singularity machine.

Matt Muir is a tech journalist and author of the online culture newsletter Web Curios