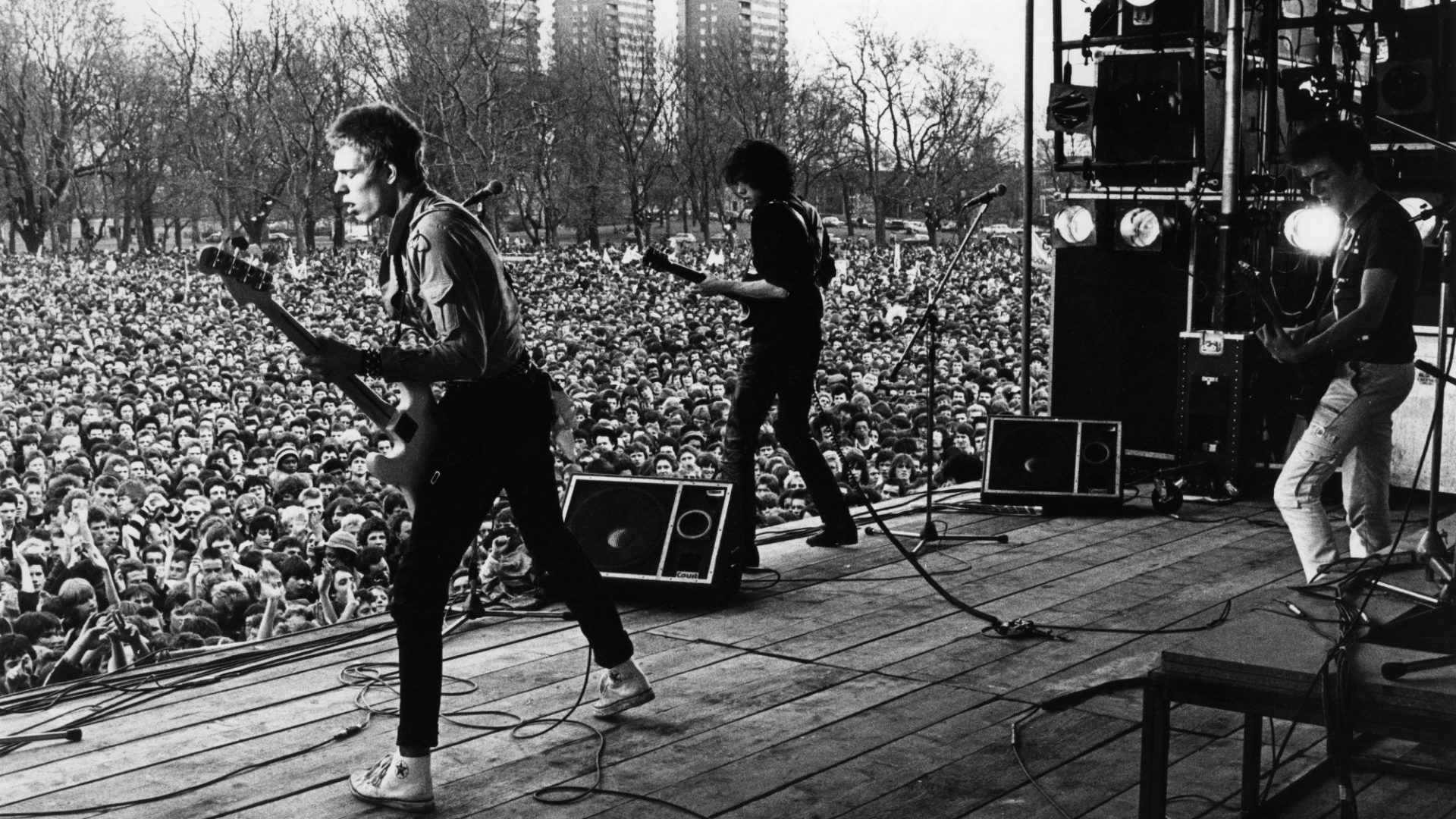

The Clash marched on stage at London’s Victoria Park and tore into Complete Control as a crowd of 80,000 surged and pogoed. It was the last day of April 1978, and confirmation that Joe Strummer’s band were now, following the Sex Pistols’ (in)glorious demise, Britain’s premier punk outfit. It was also the high watermark for Rock Against Racism (RAR), a campaign formed two years earlier that now seemed to be succeeding in its goal: to hold back the encroaching far right.

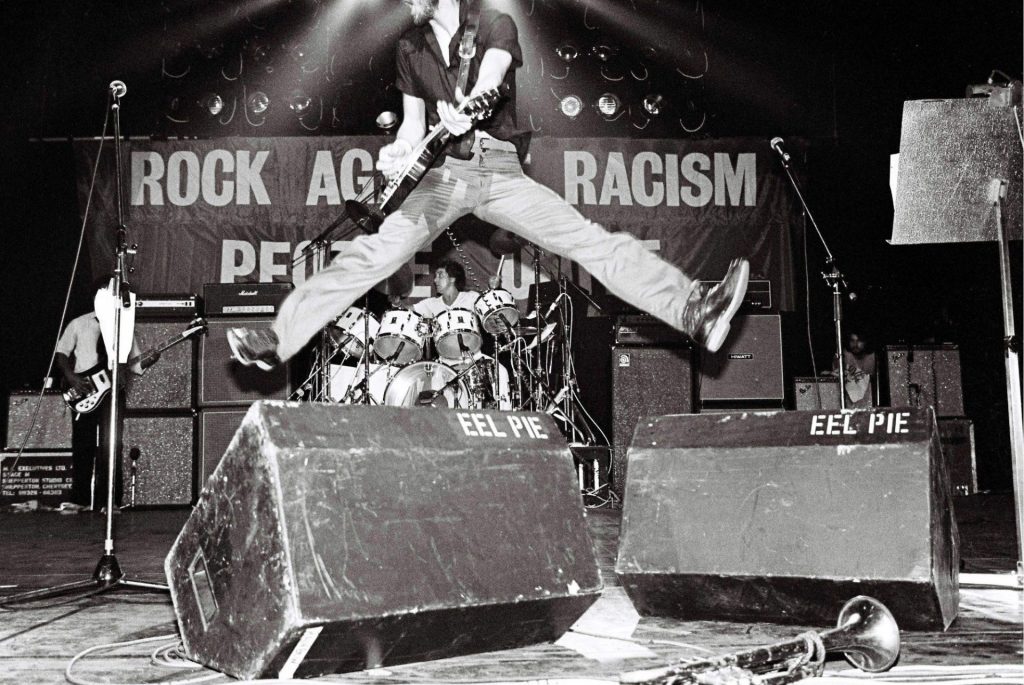

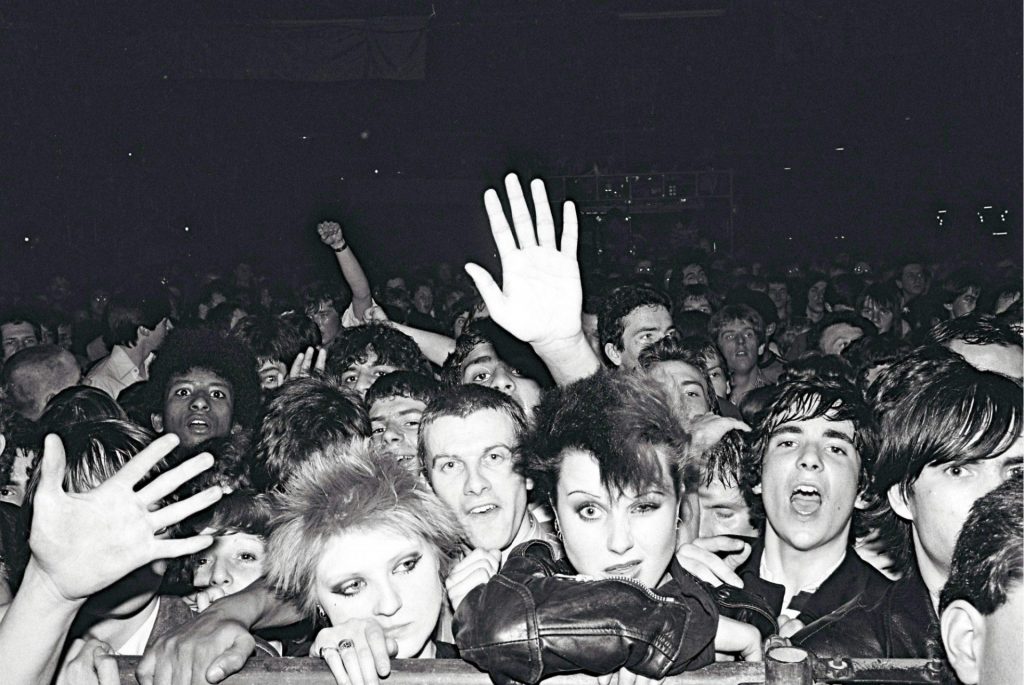

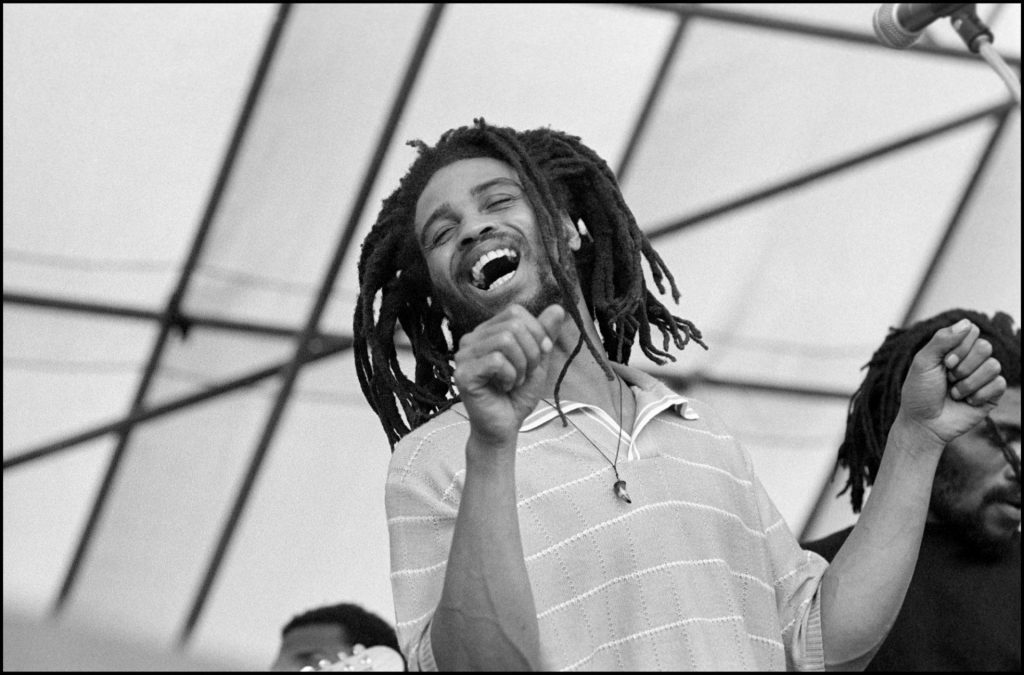

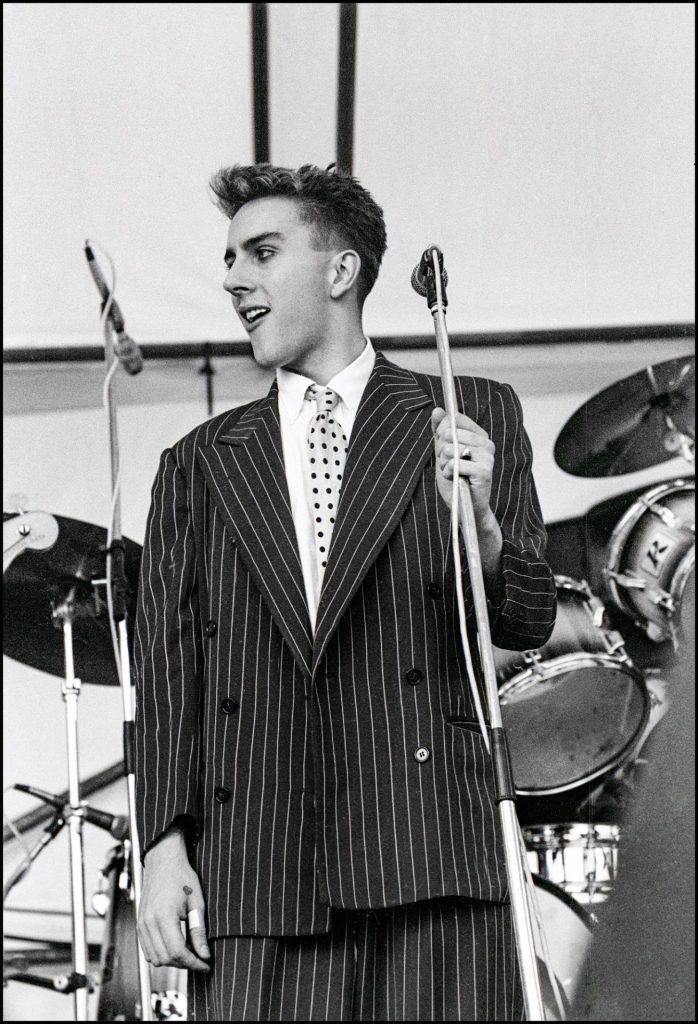

Held under the auspices of the Anti-Nazi League (ANL), the “carnival” of April 30 was an amalgam of culture and politics; images from the event, along with those of subsequent carnivals in London’s Brockwell Park, Manchester and elsewhere, have become iconic: youthful marchers with banners deriding the National Front; Dave King’s poster designs shooting arrows at the heart of fascism whilst pointing to the future; Strummer performing in front of “the kids” and the tower blocks his band claimed to represent; reggae band Steel Pulse in KKK-garb; X-Ray Spex’s Poly Styrene singing songs of identity crisis to adolescents.

“We try to use popular culture… to mobilise people,” Syd Shelton, RAR’s principal photographer, told Melody Maker in late 1977, saying the aim was to get “them to take a stand against the Front.” By 1979, dozens of local RAR “clubs” existed around the UK, organising gigs that aspired to bring rock, reggae, punk and soul together to “Love Music” and “Hate Racism”. In the charts, 2-Tone ruled the roost: the embodiment of RAR’s black-and-white-unite vision.

RAR was born in September 1976, a response to Eric Clapton’s racist rant on stage in Birmingham a month earlier. The guitarist had invited “foreigners” in the audience to raise their hands, then told them to leave, adding “Not just leave the hall, leave our country… I don’t want you here, in the room or in my country.” Even worse followed in what became a torrent of abuse.

A small gaggle of left wing activists wrote a letter to the music press calling out Clapton for his idiocy and hypocrisy (“half your music is black”), before then demanding a “rank and file movement against the racist poison in music.” Gigs began to happen, often small but thereby allowing nascent punk bands to play a music that resonated with both the tenor of the time and the grassroots DIY impulse that seemingly defined RAR’s resistance.

Support from the Socialist Workers Party enabled newssheets (Temporary Hoarding), posters, badges and banners to be designed and printed. The music press provided coverage and support, particularly after the 1977 confrontation between the National Front and anti-fascist protesters in Lewisham. In the same year, the formation of the ANL served as a more overtly political complement to RAR, bringing organisational experience towards coordinating a movement.

Clapton certainly wasn’t the only symptom of racism within British culture and politics in the 1970s. Though pop music and youth culture can be seen broadly as sites of racial integration, these remained contested, fraught and complex.

Britain, more generally, was adapting to significant postwar realignments that ranged from the end of empire and deindustrialisation to social changes wrought by consumerism, liberalisation and immigration. The postwar settlement ushered in a welfare state, but also faced challenges that undermined its vision of a New Jerusalem.

By the 1970s, a perceived combination of economic, political and social “crises” opened space for British fascism to make inroads on the back of anti-immigration policies and portents of British “decline”. The NF made electoral advances in London and the Midlands; on the streets, NF marches and racial attacks became more visible and spectacular. RAR, then, was a timely response. It has been rightly celebrated for its mobilising a cultural politics that opposed racism whilst also performing and revealing anti-racist alternatives.

Via punk and reggae, RAR tapped into two seemingly relevant and resonant musical forms, adopting and adapting their language and aesthetics to disseminate a political message. RAR’s momentum through to the 1979 general election did much to counter the influence of the National Front, discrediting racist politics and revealing the paucity of the far right’s own cultural vision. Though the advent of Thatcherism should warn against too triumphant a mythology, RAR and ANL succeeded in smothering a wave of British fascism that, for a moment, looked to be making ground.

Not surprisingly, as we today face a buoyant far right once more making headway at the ballot box and claiming the streets, the example of RAR remains a resource of hope for many on the left. The 1970s and early 1980s were a time when anti-racist rhetoric and leftist politics appeared to break through, infusing youth culture, the charts and the music press.

If Margaret Thatcher won the economic war, then culturally she struggled to embed an agenda that appeared archaic and oppressive. Could RAR’s example, therefore, now serve as a means to mobilise a resistance to Reform and the orchestrated anti-immigration marches currently gaining impetus?

To be sure, RAR revealed a moment of cultural and political synergy. However, inspiration should not beget imitation. These are different times. Popular music no longer plays so central or defining a role, be it generally or even among young people. The lines of youth culture are no longer easily defined.

The media has transformed, diversifying and fragmenting to ensure multiple – and ever more virtual – battlefields of a culture war the right has adapted to far more effectively than the left. Globalisation and the economic reforms associated with Thatcherism have transformed the British polity in ways that make comparisons to the 1970s problematic if taken beyond the superficial.

Moreover, the limits of RAR need also to be remembered. At the time, RAR and ANL were criticised for too systematically conflating racism with fascism and Nazism. The prescriptive tendencies of the left often jarred and alienated. The achievements of RAR were real, but also temporal rather than decisive.

The left likes a lineage; a sense of continuity and tradition. RAR, quite deservedly, has become part of the left’s historical forward march. But with the hope and example it provides comes also a need to remember that RAR’s resonance came from its relevance.

Suggested Reading

The Raincoats, music’s best kept secret

Even then, mobilising popular music around a pertinent issue could not resist a more general political and economic move to the right (RIP Red Wedge). To expect popular music to hold the barricades against a globally funded, tech-savvy right wing tapping into prejudices fermented in the bowels of austerity is therefore a big ask. Indeed, it is an even bigger ask now than it ever was before.

Matthew Worley is professor of modern history at the University of Reading. His books include No Future: Punk, Politics and British Youth Culture, 1976–1984 (Cambridge University Press)

Reading opens minds. It can change them. Turn the page on division and subscribe to The New World. Share our work, tell a friend, and be visible… buy the t-shirt (or the mug, or the hoodie). Go to shop.thenewworld.co.uk.

But most of all, read.