The photographs told the story; a black man with a severe case of vitiligo, the condition that bleaches skin of its pigmentation. One photo marked “Before” showed him with the dark skin he was born with. The “After” photo showed large patches of his face bleached.

The proposed headline sketched out by the Daily Mirror’s associate editor read: I USED TO BE BLACK… BUT I’M ALL WHITE NOW.

I recall nodding towards it discreetly and pulling an “eek!” expression at the editor of the paper at the time, Piers Morgan, who then came over to take a look.

After a brief flurry of debate between the associate editor (“oh fuck off! It’s not racist. It’s funny!”) and Piers, the story was eventually spiked upon the definitive ruling of the Mirror’s (ethnic minority) chief sub-editor: “Of course it’s racist.”

The year was 1996, and although this kind of blatant racism was still rife in British newspapers, it was in decline. A new generation of journalists, whose childhood in a more multicultural Britain than that of the associate editor’s generation, was gradually diluting a thickly toxic newsroom culture that casually demonised ethnic minorities as standard.

They also had, for the first time, a rulebook they could point to.

A series of traumatic national events in the 1980s – not just race-related, but of gross misconduct by the national press generally – had led to the establishment in 1991 of the Press Complaints Commission and its Editors’ Code of Practice. Within the code, Clause 12 dealt with discrimination:

i) The press must avoid prejudicial or pejorative reference to an individual’s race, colour, religion, gender, sexual orientation or to any physical or mental illness or disability.

ii) Details of an individual’s race, colour, religion, sexual orientation, physical or mental illness or disability must be avoided unless genuinely relevant to the story.

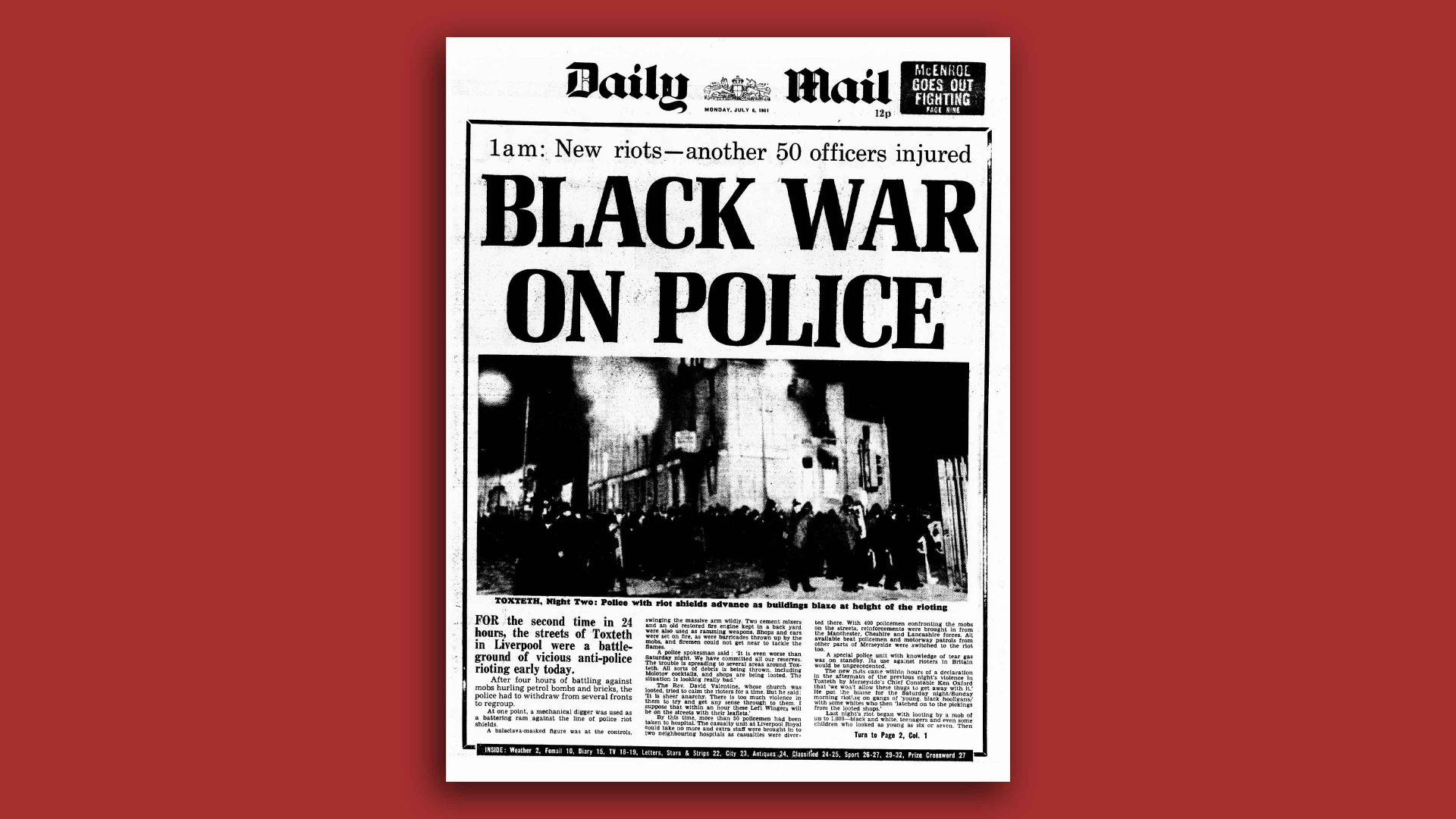

It wasn’t perfect. But it seemed to mark a turning point: no longer could the press publish “BLACK MUGGER” headlines and pretend it was just neutral information.

From the smallest local newspapers to the biggest broadsheet papers of record, it had long been a matter of routine to note if a criminal was black in a way a white equivalent never would be.

That the rationale for this racism was probably more commercial – appealing to the innate prejudices of their majority-white readership – than political or philosophical is debatable. Certainly, it was deliberate.

As far back as 1970, the great Harold Evans, editor of the Sunday Times, identified the racism at the heart of newspaper reporting in the UK.

In an article for BBC-published magazine the Listener, he lambasted his fellow editors. “Stealthily in Britain,” he wrote, “the malformed seeds of prejudice have been watered by a rain of false statistics and stories.”

He went on to state the obvious: that “the way race is reported can uniquely affect the reality of the subject itself.” Or, in the plain English beloved of Evans, keep telling your white readers that ethnic minorities are ruining Britain and your white readers will treat ethnic minorities accordingly.

To nobody’s great surprise, the introduction of the Editors’ Code of Practice did not magic racism out of Britain’s media at a stroke. It simply meant newspapers had to use different nouns.

If “Blacks” and “Asians” stopped being the target, they were replaced in right wing newspaper headlines with a more pernicious nomenclature: “migrants” and “asylum seekers”.

In the eyes of many, it all added up to the same thing, and the so-called regulators, with their semantic escapology when it came to upholding the spirit of the original clauses, were repeatedly complicit in the business-as-usual approach.

Take two rulings indicative of how little Clause 12 actually meant. When Katie Hopkins compared migrants to “cockroaches” in the Sun, IPSO, the self-regulator which had succeeded the PCC, decided Clause 12 didn’t apply – because she hadn’t singled out an individual. Dehumanising a whole category of people passed the test.

When former editor of the Sun, Kelvin MacKenzie, used his column in the newspaper to question why a Muslim woman in a hijab was presenting coverage of a terror attack, the regulator again said this was commentary about a religion and a debate about “symbols” – not a prejudicial attack on a named person on grounds of faith.

More chronic still were the attritional front-page headlines. They were relentless. As Liz Gerrard reported so forensically in the pages of this magazine, the abject racism in right wing press reporting – in particular the Daily Mail, Sun and, most blatantly, the Express – was every bit as bad this century as it had been in the 1970s and 80s, reaching a crescendo of front-page asylum-seeker hatred in the run-up to the Brexit referendum.

Harry Evans’ malformed seeds of prejudice were still being well-irrigated on an almost daily basis, all of which would have been damaging enough for people of colour living in the UK, but now there was another factor in the mix. One which made the reporting of race in the UK an exponentially more complicated challenge: social media.

The aftermath of the ghastly murders of three little girls in Southport in July 2024 exposed most vividly how reporting of race had entered a new, more complicated, more dangerous phase.

The killer was a psychopathic British national, Axel Rudakubana, born in Cardiff to a Christian Rwandan family. He happened to be black. In the absence of any official reports, rumours that he was a Muslim asylum seeker quickly swept social media, bolstered by conspiracy theories and anti-migrant polemics from far right commentators both on social media and the press. The result was a series of attacks on mosques, asylum hotels, and random people of colour.

Michael Weston King, the grandfather of six-year-old Bebe King, murdered by Rudakubana, told the Guardian: “I not only speak for myself but for all of the King family when I say that the ethnicity of any perpetrator, or indeed their immigration status, is completely irrelevant. Mental health issues, and the propensity to commit crime, happens in any ethnicity, nationality or race.”

He chose to speak out this August, after the then home secretary Yvette Cooper welcomed new police guidelines for disclosing racial and ethnic information of suspects following high-profile crimes, as called for by – among others – Reform.

Suggested Reading

Racism in Britain is getting worse

Cooper’s support for the new guidelines was, Bebe’s grandfather said, “kowtowing to the likes of Farage” who he accused of making “political gain from our tragedy, only causing further misery to us and others, which was despicable”.

This weekend, a collection of more than 50 anti-racist organisations, led by the Runnymede Trust, wrote to the new home secretary, Shabana Mahmoud, demanding this new police guidance be scrapped as it is already resulting – predictably enough – in a massive uptick in prejudicial reporting.

In the three full months since the introduction, there has been a five-fold increase in use of the phrase “asylum seeker” in newspaper articles on serious crime. It’s almost as though the right wing press saw the new guidance as a green light to forget about any artifice of responsibility around reporting on race.

“The guidance was offered as an attempt to dispel misinformation… In practice it has had the opposite effect, becoming a catalyst for crime reporting reminiscent of the 1970s and 1980s – reviving a focus on race and migration status,” the report stated.

We had a taste of how horribly this new policy could backfire last month when a lone assailant embarked on a stabbing spree on an LNER train in Cambridgeshire.

Initially, police described two suspects as being a 32-year-old black British national and a 35-year-old British national of Caribbean descent, both born in the UK.

Naturally, the fact that two men had been arrested led many on social media to speculate this must have been a coordinated terror attack. The fact they were both identified as black sealed the deal.

News UK’s Talk Radio gave ex-Reform MP Rupert Lowe a platform to claim that “the British state has been complicit in a crime like this” because the government “haven’t done enough to deport illegal immigrants”.

Far right influencer Ada Lluch tweeted to her 440,000 followers: “We are all at risk. Send them back!!!”

And Andrew Neil asked on X what “would motivate two men in their mid-30s to run through a train stabbing anyone they came across?” Many of his followers thought the question was a leading one and provided him with their answer: “Maybe Allahu Akbar is a clue” went one particularly well-appreciated response.

As we know, it wasn’t terrorism and there weren’t two attackers. Just one. A 32-year-old Brit named Anthony Williams from Peterborough. Who just happens to be black.

There are other indications we are heading back into the dark days of racist reporting. Last week, Paul Marshall’s GB News hosted a TV discussion based on a study by a publicity-loving solicitor called Marcus Johnstone of court appearances of people with “foreign-sounding, non-British” names. We don’t know for sure what qualified as a non-British-sounding name, but we can safely bet it wasn’t names like Farage, Pochin or Kruger.

The evidence was so outrageously shonky as to be laughable, and is now subject to multiple Ofcom complaints. But as a guide to the sense of licence right wing media now feels when it comes to reporting the topic of race, it is as bad, if not worse, than anything passing for journalism in the 80s.

At least it was blatant in its racism. More worrying is the return to routine identification of ethnic identity in reporting serious crime from more trustworthy outlets.

A month ago, the BBC website reported: “Afghan refugee faces murder trial for fatal stabbing”.

If the suspect was white and British-born, this story would most likely never have made the website of the national broadcaster, but just as the tabloids of the 1970s knew that race-baiting sold papers, the BBC understands there is an appetite for stories of asylum seekers running amok in our streets, regardless of whether it’s a fair representation of reality.

How many times on the BBC website have headlines read: “White British man…” in relation to high-profile crime? The answer is, of course, zero – but it is notable that the BBC reports of the car being driven into crowds at the Liverpool FC victory parade last summer noted the suspect’s whiteness in the first sentence – information deemed in the public interest lest a few more mosques were bricked before the truth got its boots on.

What, then, of the Yorkshire rape gangs scandal? It is, as TNW columnist Sonia Sodha wrote recently in the Independent, an “uncomfortable fact that culture and racism have clearly played some sort of role, reflected in the disproportionate number of Asian perpetrators involved in the rape gangs in areas like Greater Manchester and West Yorkshire” and that those facts have never been properly confronted.

That lack of confronting the problems of integration and race – where those problems are real and not imagined – leaves, Sonia concluded, “the issue ripe for manipulation by those whose main motivation is to sow division.”

The answer, surely, is open fact-based debate about an issue that is, in real time, defining what Britain is, and what Britain hopes to be.

So let’s have the thorough collation of real ethnicity data by the Department of Justice (currently partial at best), and a debate on the reality of what it reveals. The alternative is the “foreign-sounding names” school of journalism.

Let’s have the courage to openly debate where the ambitions of multiculturalism have objectively failed local communities. The alternative is to allow the far right to claim a suppression of the truth.

And let’s have a new code of practice for editors demanding a clear rationale for any race or ethnicity discrimination in reporting.

The alternative is what we dealt with in the 1970s and 80s. Which is to say, sadly, what we’re dealing with today.

Matt Kelly is the founder and editor-in-chief of The New World