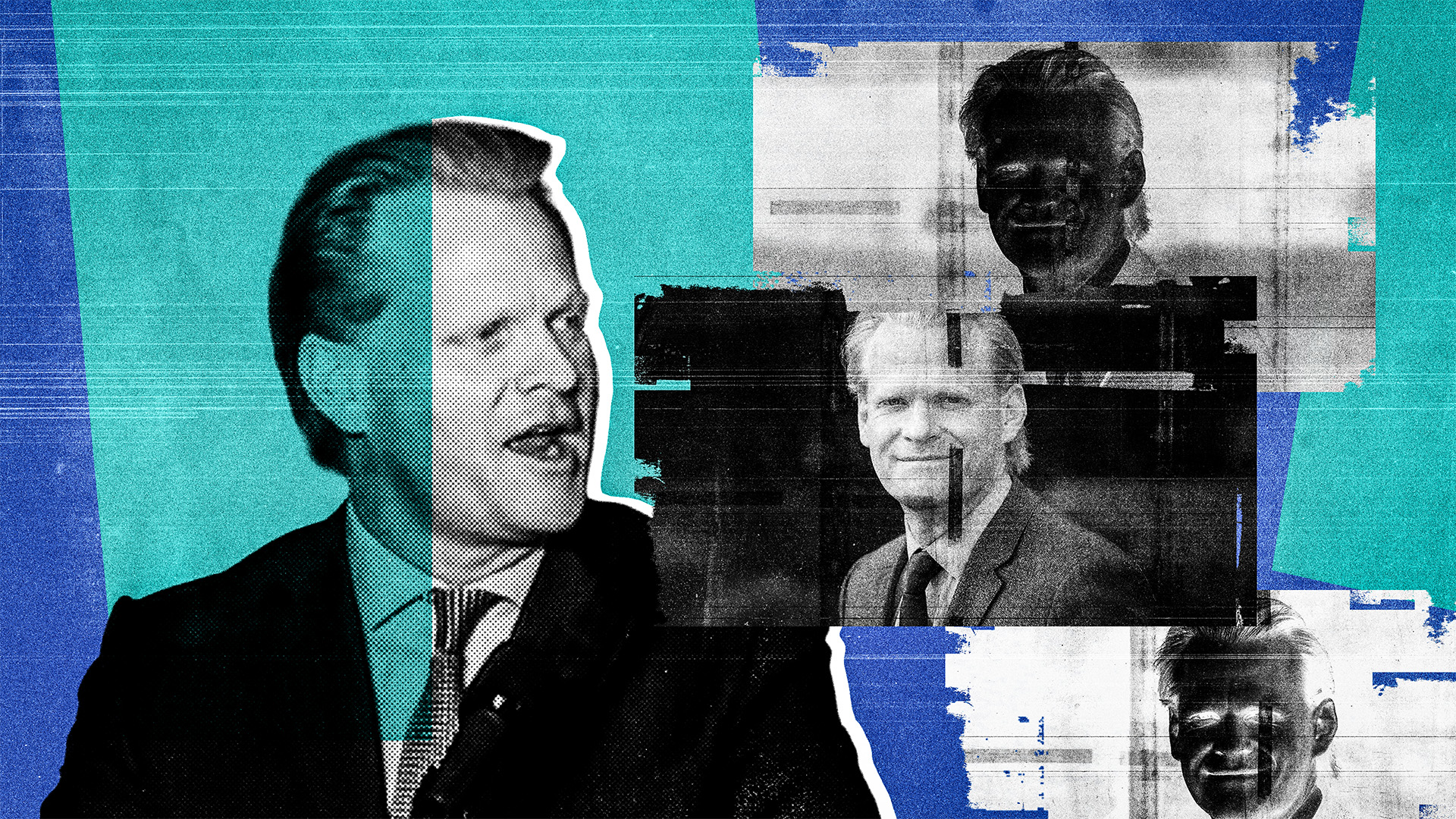

Do you know about James Orr? James Orr would like it if you did. Reform’s new “kingmaker” has been doing his best to make himself appear unavoidable. If you look him up today, you will find that he has seemingly been interviewed by every single person with a microphone or a camera in Britain or America. He has talked to national newspapers and to the YouTube channels of complete unknowns. He’s pontificated on obscure websites and chatted away on mainstream television. On October 19, he was announced as a new adviser to Nigel Farage.

The 46-year-old is technically an associate professor at Cambridge University, teaching the philosophy of religion at the Faculty of Divinity, but these days that feels like a bit of an aside. More important are his roles at the Edmund Burke Foundation, the Free Speech Union, the Roger Scruton Legacy Foundation and the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship.

If that feels like too large a collection of opaque names for you, don’t worry. All you need to know, really, is that James Orr has views, and he has friends, and he wants you to know about both of them.

His most famous acquaintance is JD Vance, the vice president of the United States. Orr has, on occasion, been described as his “British sherpa”, and the pair enjoyed quite a high-profile barbecue in the Cotswolds over the summer. This may have been the point at which you first heard about him.

If, however, your interest in current affairs is especially keen, you probably saw his name pop up back in 2023, at the National Conservatism Conference. It felt like quite a shocking event back then. It was, in retrospect, a harbinger of what was to come. Over in London, prominent Conservative politicians, from Michael Gove to Suella Braverman, happily mingled with a wide assortment of cranks and freaks.

There was, once upon a time, a reasonably clear line between the parliamentary Tory party and the more extreme fringes of the right, but the conference showed that it was beginning to disappear. Two years on, it’s all but gone – but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

NatCon opened with a 20-minute speech titled “faith, family, flag, freedom”. Seconds into his remarks, Orr joked that those first three “F-words” were “guaranteed to induce fainting fits from Hampstead to Hackney”. Schoolboyish use of alliteration aside, the introduction felt unintentionally revealing.

James Orr has opinions and they were not built in a vacuum: like a true culture warrior, his sights are forever set on the great enemy. Back in that room in 2023, he ranted against “drag queen story hour” and public bodies flying the “rectangular kaleidoscope”, also occasionally known as the Pride flag.

Since then he has argued, in various places, that “toxic femininity is a thing, as much as toxic masculinity is”, and that abortion should be banned at all stages, including in pregnancies that resulted from rape. He believes the Capitol riots of 2021 were at least partly an invention of the liberal press, and has said that multiculturalism is a “disastrous experiment”. He called people who protested against the building of a new mosque in the Lake District “heroes”, and repeatedly dismissed the war in Ukraine as “a regional Slavic conflict”.

He wrote that the former first minister of Scotland Humza Yousaf wasn’t meaningfully Scottish, and he believes that public sector workers are “loyal to their paymasters; the so-called rainbow people”. He said that there are “vast swathes of London where you can’t send your kids to school because English is just not spoken anymore” and he spoke of “the mass rape of England’s daughters by rapist foreigners from morally backward cultures who we’ve hosted and paid for their accommodation for years”. He would like the Supreme Court to be dissolved, and described Britain’s diversity as a “debilitating weakness”.

He is, to sum up, someone who wouldn’t have been welcomed anywhere near the British political mainstream until very recently. Even now, you may be wondering why his views, corrosive as they are, are being broadcast anywhere.

One possible explanation is as frustrating as it’s obvious. James Orr is a recognisable type, and journalists like that. He was profiled by the Times over the summer and readers were told, breathlessly, about his “shelves filled by volumes of Immanuel Kant in the original German and Thucydides in the original Greek”. There were – get this! – “cigar butts in the ashtray”. What a guy, eh?

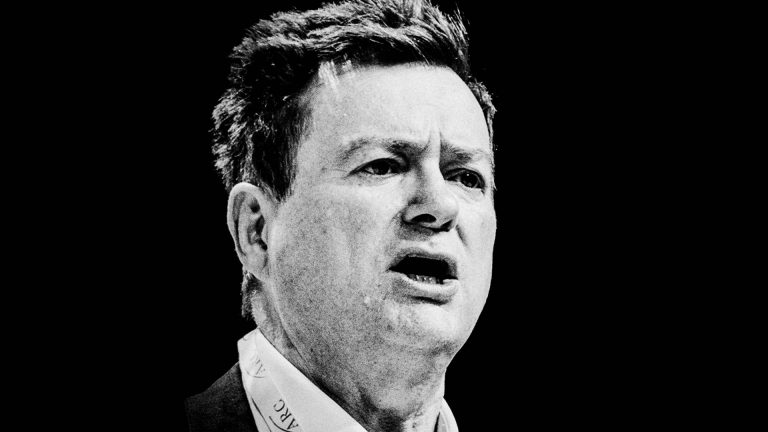

It should go without saying that his trademark look – the pale ginger hair, piercing blue eyes and often double-breasted jacket – works in his favour here. Not every right-wing thinker needs to look like he could play Moriarty in a German national broadcast adaptation of Sherlock Holmes, but it helps. Similarly, his professional background hardly is a hindrance. Would Politico have profiled him if they hadn’t been able to dub him Vance’s “English philosopher king”?

Sometimes a story has to look like “man bites dog” to make it to print but, more often than not, a well-trodden path will look most attractive to incurious or exhausted hacks. Is a well-heeled white man somehow perceived to be the brain behind some political movement? Is he, perchance, clever and articulate, and never at risk of being described as camera-shy? Well then ambassador, aren’t you spoiling us!

Still, there are some valid reasons why Orr does deserve his sliver of the spotlight. Who he is may not wholly matter, but who he knows absolutely does. He became friends with Vance when they got talking about their faith, but the VP is only one part of the puzzle. You probably missed it at the time, but he first made waves in 2021, back when Cambridge students wrote an open letter condemning him by name.

“James Orr, together with other members of the faculty and wider university, are part of an organised network, formed with the direct involvement of Peter Thiel’s chief of staff, Charles Vaughan,” they wrote in their petition. The group was, they warned, promoting “an ideology that is fundamentally, indeed deliberately hostile, to the university’s aims and values”.

Suggested Reading

Robert Jenrick, the hollow man

Said network had invited Thiel, the controversial and viscerally odd tech billionaire, to speak on campus. Another of their guests was Charles Murray, the author of The Bell Curve, which argued that some races were genetically cleverer than others.

Since then, Orr has brought his network closer to home, as he and his wife run what he calls a “conservative kibbutz” from their residence near Cambridge. “The Moorings” has more than enough space to both host events and be a home to promising right-wing and Catholic university students.

When Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson needed a space in which to work on his latest book, he moved into a shepherd’s hut on the Moorings’ ground. Peterson has, famously, spent much of the past few years on the vanguard of the global culture wars.

Writer and Orbán cheerleader Rob Dreher has also stayed there, writing that “people pass through here for parties, or for a weekend, or even for semesters in graduate school – and it changes them. They meet others here who share their views. Every time I’ve been here, I’ve observed these parties they have, where conservative and Christian intellectuals, journalists, clerics and others meet to have fellowship, trade ideas, and make contacts.”

Danny Kruger, the firebrand Conservative turned Reform MP, has naturally kipped at the Moorings in the past, as has hard-right commentator Douglas Murray. The latter recently appeared on a podcast hosted by none other than Orr himself. His other guests have so far included commentator Matt Goodwin, “reactionary feminist” Mary Harrington and online provocateur Konstantin Kisin.

Naturally, Orr also appeared on Kisin’s podcast Triggernometry two years ago, in an episode titled “the barbarians aren’t at the gates… they’re already here!” Similarly, Harrington and Orr were on the same side of an Unherd debate earlier this year, arguing that “this house welcomes the new Trump era”.

What is especially interesting about this tight-knit group of broadly ideologically aligned individuals is that they have, for the most part, chosen not to attach themselves to any political parties. Though Orr is now hitching his wagon to the Farage train, it took him a long time to do so, and many people around him are yet to make the jump.

Not too long ago, things would have been different. For as long as anyone can remember, the obvious path to power on the right in Britain would have been to infiltrate the Conservatives, using money and connections to get their MPs to say and do the right things. This is no longer the case.

Scanning Orr’s Twitter account means seeing him spending the past six months flirting with Reform, yes, but also with shadow cabinet minister Robert Jenrick, and even with Blue Labour. Earlier this year, he also happily appeared on a panel with Rupert Lowe, now leader of the one-man band Restore Britain. In an interview about his organisation, the Centre for a Better Britain, Orr said he would consider training up the right “pro-nation” Green politicians if they came knocking.

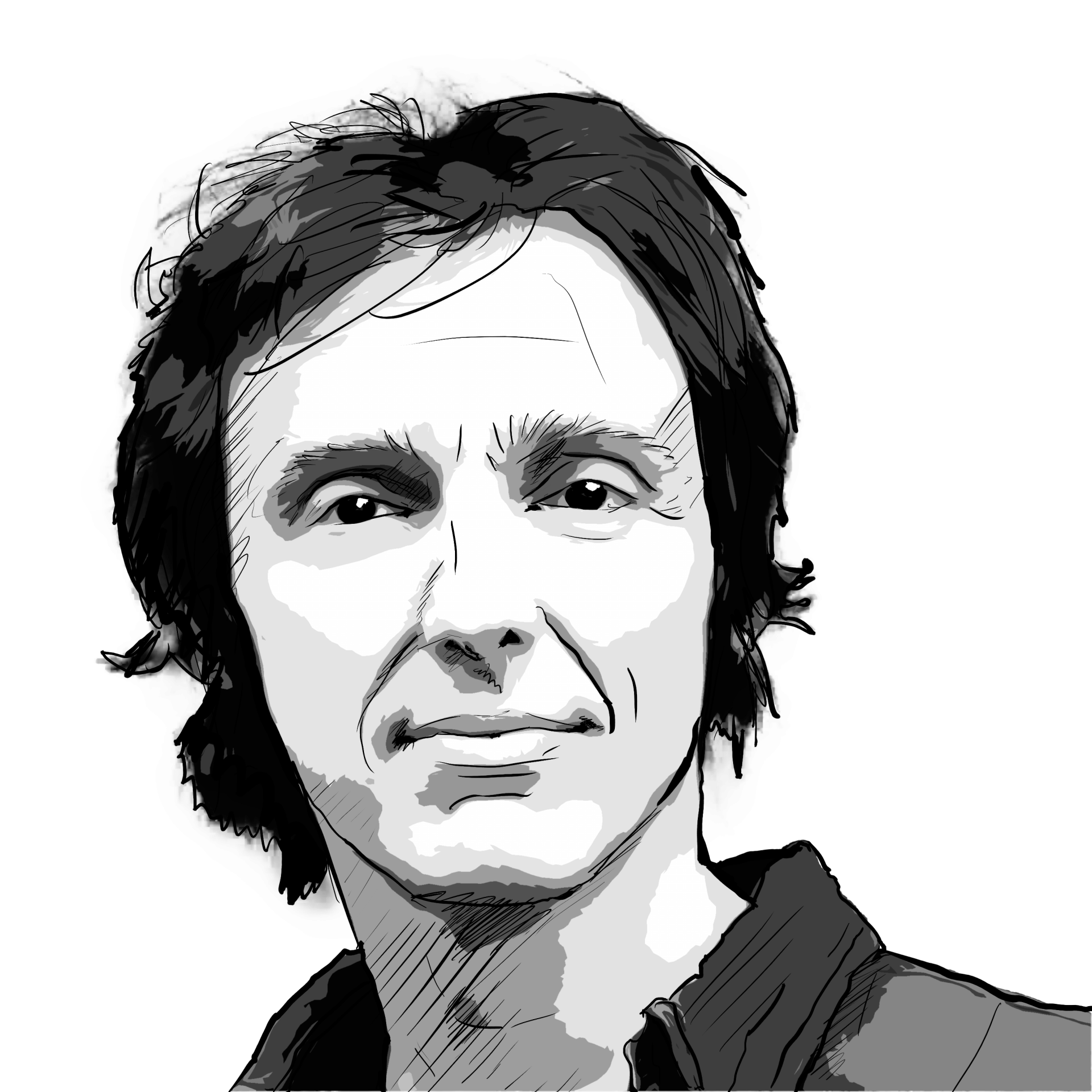

It is both quite a novel approach to politics in Britain and, for those with a long memory, a reminder that there is nothing new under the sun. According to Aurelien Mondon, a professor of philosophy and co-convenor of the Reactionary Politics Research Network, Orr is merely a “part of a long tradition in far-right politics”.

Back in the 1970s, seeing their movement at its lowest ebb, French members of the “Nouvelle Droite”, a radical right intellectual movement, “decided to take their time and try to recreate a new discourse that was more adapted to the times they lived in”.

“People like Alain de Benoist [whom Steve Bannon admires] always stayed outside; they advised and talked to far-right parties, but they also talked to other people. What they did was borrow ideas from the left, from Antonio Gramsci in particular, about hegemony and the idea that to gain political power, you first need to gain cultural power.”

This is a helpful lens through which to look at Orr’s online presence. Attempting to read and watch everything he has said in the past few years feels like a fool’s errand. Some YouTube videos have tens of thousands of views and others only have hundreds, but that doesn’t really matter. Similarly, it isn’t all that relevant that this new right movement seems to mostly consist of four small reactionaries stuffed inside a big trenchcoat.

What does is that, like peacocks, they’ve managed to make themselves appear both bigger and brighter than they actually are. Not every interview or podcast will reach everyone but, with each new media appearance, there is a chance that they will get to the ears or eyeballs of someone they wouldn’t have got to otherwise.

In our hyper-connected yet wildly fragmented information ecosystem, it is a much better use of someone’s time than spending a few grand on the Conservative party, in exchange for some rubber chicken and dry conversation with a junior shadow minister. Instead of trying to directly influence politicians, Orr and his ilk can yank the Overton window in their direction instead, then wait for MPs to move to what they believe is the new mainstream.

According to Alan Finlayson, a professor at the University of East Anglia, “they’re providing not just a set of policy positions, but a broader worldview that attempts to present a diagnosis of what’s gone wrong, who’s to blame for it, what we should do about it. That is flourishing in part because no one else is doing that.”

“On a lot of radical right social media, the core framing is ‘I can explain to you why everything’s going terrible. This is what’s happening. This is what’s going on’. They offer a vocabulary people can use.”

Suggested Reading

Paul Marshall, the man who owns the right

It has been worryingly successful so far, as “that battle for intellectual and moral leadership is not really being fought by other parties. There’s a demoralisation, and there’s an institutional withdrawal from that sort of activity.”

At risk of stating the obvious, we are currently living through disquieting times, and have done so for some time now. Deprived of hope and ideas, people will turn to the internet to find answers, and stumble upon, say, a conversation with Orr titled “can Britain still be saved?”

Dealing with this dynamic means reckoning with the elephant in the room, namely that, as Mondon put it, “the mainstreaming of far-right politics is very much a result of the failure of the liberal hegemony, which doesn’t have any answers to the many crises we are facing”.

Of course, the great irony is that this reactionary right doesn’t have the answers either, as nothing it offers is new. Banning abortion would not solve the productivity problem. Being more hostile to LGBTQ people would not do anything to address, say, regional inequalities. Dramatically cutting immigration would, according to just about any study done on the topic, take a gun to the economy’s temple. Letting Putin win in Ukraine would be awful for Europe. This would, in turn, be catastrophic for Britain, a neighbour and close trading associate of the continent.

None of the substance is new but, despite it all, the energy and intensity remain enticing to many. It’s also not being countered by any of the people who should worry about these things. “A key feature of contemporary politics is the significant intellectual, ideological collapse of the left”, Finlayson said, pointing to the lack of big thinkers in Cabinet, as well as the dearth of think tanks shaping Starmer’s direction of travel. The reactionary right may not have a lot of fresh, exciting new things to offer, but neither does anyone else.

There is also an asymmetry at play here which ought to be mentioned. When James Orr and his “polished syllables” effortlessly quote Yeats in an interview with House Magazine, he is treated as a beguiling thinker. When Jeremy Corbyn confessed to having loved James Joyce’s Ulysses, he was mocked by commentators from across the spectrum.

There is an anti-intellectual strand in contemporary British politics and it applies to everyone but the right-wing. No Labour politician can succeed while appearing even slightly pompous, but advocating policies that would have made Nick Griffin blush in 2010 gives you the right to be grandiloquent and get away with it. Somehow it is both accepted that rhetorical flourish can and will attract voters, and forbidden for the left to use that to its advantage.

Should it really be a surprise that, as a result, the reactionaries get to seem exciting and fizzing with ideas? After all, they’re the only ones allowed to have a good time. The Labour party is floundering in power and the Conservatives are yet to atone for their sins. The Greens will always be treated with disdain by swathes of Fleet Street, and the Lib Dems are forever condemned to remain a sideshow.

Thanks to their shrewd, strategic mewling about free speech, this new and old breed of radical right-wingers now get to say and do whatever they want, bringing the political mainstream closer to them in the process. Or, as Mondo argued: “liberals have dug their own grave by falling for obvious traps that were laid by the far-right”. Oh, and crucially: they’re blatantly having fun doing it. James Orr rose seemingly from nowhere and you could almost believe that, at some point, he stumbled upon a genie willing to grant him a smooth and perfect life.

What should concern us all is that he has seemingly spent years quietly building up both his rhetoric and his networks, and is now handing them to Nigel Farage on a plate.

“That infrastructure has been in formation for a while and has found its moment”, Finlayson said. In an ideal world, Orr wouldn’t be an unstoppable force, but is anyone ready to stop him?