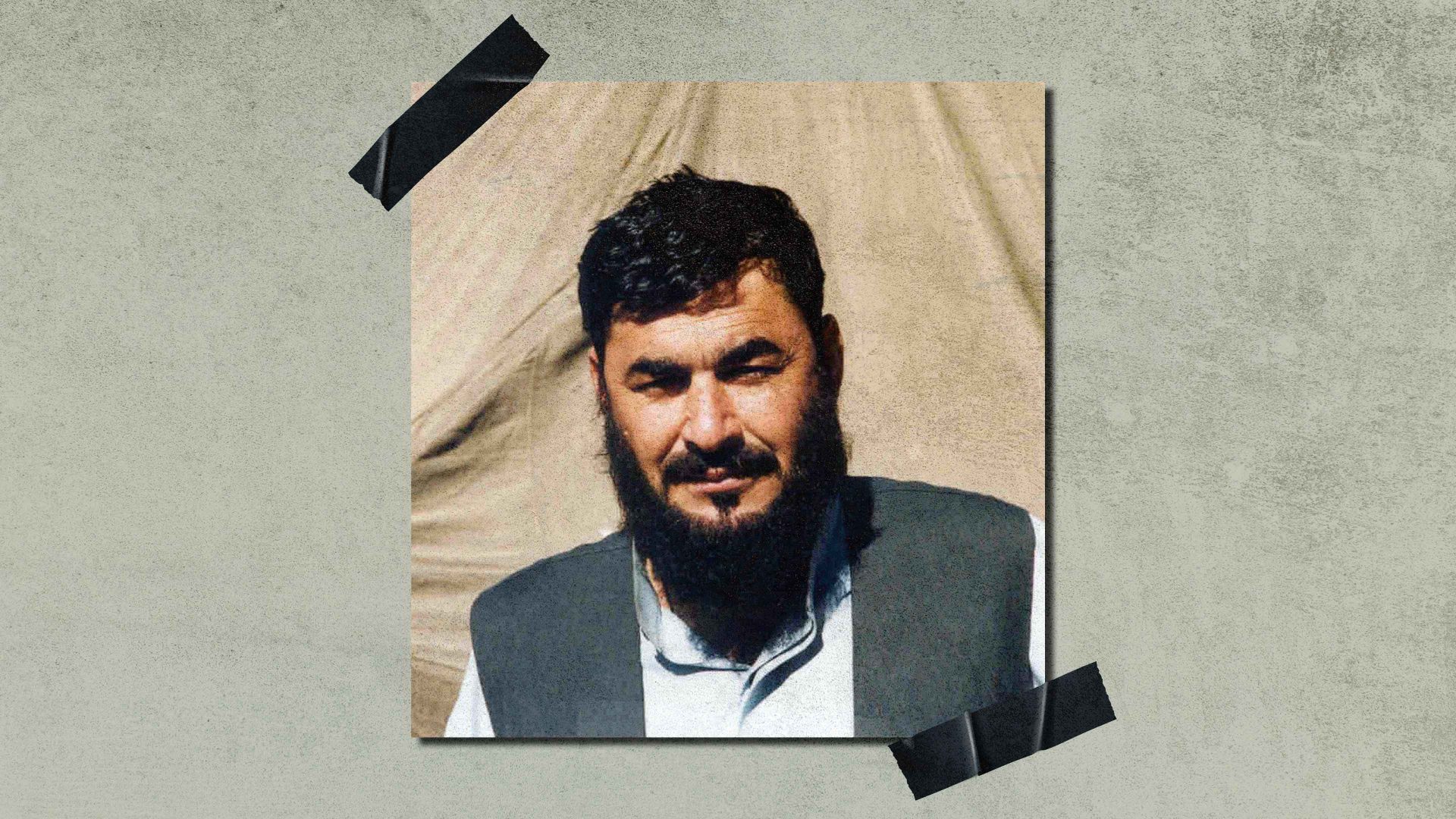

Bashir Noorzai is as dangerous as he is charismatic: a narco-tycoon whose shadow stretches far beyond the global drugs trade into the heart of the Taliban regime he helped to create.

After his early release from prison in the United States, in a controversial swap for an American hostage, he is back in Afghanistan, the Taliban’s prodigal hero, expanding his heroin and meth empire into control of the country’s untapped mineral wealth.

Afghanistan has long been viewed through the prism of conflict and military intervention. Now it is emerging as a key player in the global competition for geopolitical influence — and the resources that will underpin it.

President Donald Trump’s second-term focus on critical minerals and rare earths is tightly bound to his broader vision of national security, and his intensifying rivalry with China to dominate the technologies of tomorrow.

He is ramping up America’s push to secure access to those raw materials, from Greenland to Canada and Ukraine. Amid the threats, deals and trade-offs, the spotlight is shifting back to Afghanistan.

There’s much that Afghanistan has that Trump and China regard as vital in their race to the future. Figures from the U.S. Geological Survey and Defence Department have estimated the value of Afghanistan’s natural resources at between $1 trillion and $3 trillion.

The country has ample reserves of copper, gold, cobalt, iron, chromite, graphite, and lithium. Its list of rare earth elements reads like a casting call of Marvel characters – neodymium, praseodymium, cerium, lanthanum, yttrium, dysprosium, samarium. Much, as fate would have it, are in Noorzai’s tribal stamping grounds.

To tap this treasure trove, Trump may first have to contend with Noorzai, a man not unlike himself in some striking ways. A master deal-maker, Noorzai has turned his family business into a global brand — most famously associated with “Crown” opium — undeterred by inconveniences like criminal indictments or jail time.

A tribal aristocrat from the Pashtun belt that spans the lawless Afghanistan-Pakistan borderlands, Noorzai stands in stark contrast to Trump in one key respect: he avoids the spotlight. Yet he is one of the most powerful figures few have ever heard of — and the gatekeeper to those minerals and rare earths crucial to technology and defence capabilities.

With his deep ties to China, Iran, and Pakistan, Noorzai is uniquely positioned to benefit from this new rush for riches, sitting at the right hand of the Taliban’s Supreme Leader, Haibatullah Arkhundzada, as chief comptroller of the regime’s financial affairs, according to multiple sources familiar with the inner working of the Taliban’s governing structure.

Beijing, leveraging decades of quiet ties to the Taliban, has secured multi-million-dollar mining deals since aiding the group’s return to power in August, 2021, placing China in pole position in the global scramble for Afghanistan’s mostly untapped resources.

Like it or not, Trump helped pave the way. His 2020 deal with the Taliban promised a full U.S. withdrawal, which unravelled into the debacle he now pins on his successor-cum-predecessor, Joe Biden.

Now he wants back in. Afghan and Western sources in Kabul, with access to senior officials of both sides, say Washington has re-opened talks with its former enemy, aiming to establish a new relationship built on strict conditions. Chief among them: cut ties with China.

In recent weeks, said sources speaking anonymously for their own security, Trump Administration officials have made their message to the Taliban unmistakably clear: China out, and America in.

The United States wants “critical minerals and rare earths are for the exclusive access of U.S. companies,” a source said.

Noorzai saw it coming. Freed in September 2022, on Biden’s orders, he wasted no time in reclaiming his throne: growing his narcotics empire; embedding loyalists around the Supreme Leader; expanding his hawala network; and locking down contracts across Afghanistan’s resource spectrum. His take is said to be a cool 18 per cent.

Suggested Reading

The father of Iran’s nuclear programme

He returned not as a relic of past wars, but as a calculating force behind the Taliban’s financial future. His story offers a lens into how influence flows in Afghanistan: not through ideology, but with cash, commodities, and control.

Born the heir to the biggest and most powerful Pashtun clan, Noorzai rose from smuggler to statesman, a master of the grey zones where loyalty, power, wealth and violence intersect.

The American lawyer who handled his appeals, Alan Seidler, described Noorzai as “the nicest man you’d ever want to meet”. Yet he is also regarded by some as the “godfather” of the militia that later morphed into the Taliban.

After dabbling in mujahideen politics during the Soviet occupation of the 1980s, the young Noorzai decided the surest path to wealth was to return to the family plantations. In the 1990s, during the civil war that followed the Soviet retreat, he bankrolled the Taliban to protect his supply lines, ensuring his raw opium made it safely from poppy fields to heroin factories across southern Afghanistan and western Pakistan.

“He got them their first motorcycle, their first pickup truck, their first truck. No Haji Bashir, no wheels. It’s as simple as that,” said a European diplomat who has tracked Noorzai’s role in the Taliban’s rise.

“He is the guy who got it off the ground. The money has a name and it is Haji Bashir. Having involvement since the creation, he is the godfather of the movement,” the diplomat said, asking that he not be identified.

Seeing the group’s potential to consolidate power in Helmand and Kandahar – and to safeguard his own business – Noorzai played a key role in selecting their leader, a little-known village cleric named Mullah Mohammad Omar who would later adopt the title Amir al-Mu’minin, or Commander of the Faithful, to evoke religious legitimacy.

Timing worked in their favour. As warlords tore the country apart, the Taliban stepped in to fill the law-and-order void. When they entered Kabul in 1996, residents exhausted by years of chaos greeted them with flowers and tears.

Suggested Reading

Trump’s own Afghan scandal

Order quickly hardened into isolation and deprivation. The Taliban sheltered Osama bin Laden, whose Al Qaeda network planned the 9/11 attacks under their protection. In retaliation, the United States bombed the regime out of power. Bin Laden and the Taliban leadership escaped to Pakistan, and Afghanistan entered a new phase of U.S. occupation and insurgency.

Noorzai tried to adapt. He offered help recovering Stinger missiles and surplus ordnance the US military feared could resurface in Taliban hands.

But his rivals, many of whom had remained in exile during Taliban rule, returned with US backing and quickly rose to power. American intelligence sources said that Noorzai feared he would be targeted and rendered to the oblivion of Guantanamo Bay. So he disappeared back across the border, to the protection that Pakistan’s security services offered to him and to the Taliban.

Noorzai was untraceable until 2004, when US intelligence agents lured him out of hiding. They believed he could help trace the financial networks behind 9/11 and offered him protection in return for information.

Noorzai agreed, thinking he was walking into a deal. Instead, he walked into a trap. By then a designated drugs kingpin, he nevertheless flew with the Americans to New York, where he was arrested, charged, and, in 2009, sentenced to life imprisonment as a major heroin trafficker.

Transcripts of his 2008 trial, before Judge Denny Chin at the District Court in the Southern District of New York, reveal Noorzai’s symbiotic relationship with the Taliban and the heroin business –- none could have survived without the others. Seidler, the lawyer, said Noorzai was lured to the United States under false pretences, believing he would be meeting with U.S. officials to provide information about 9/11 funding and planning, as well as Taliban ties to Al Qaeda, possibly in return for immunity.

“The whole episode was a sham,” said Seidler, who believes the spies who brought Noorzai in from the cold likely had no idea that they were part of a well-laid plan by US law enforcement. “The fix was in, it was pre-ordained so they could use him at some point in the future as a swap for someone” held hostage by the Taliban, Seidler said by phone from New York. “They didn’t bring him here because he was selling poppies.”

Javed Noorani, a Washington D.C.-based mining sector expert, said since his return to Afghanistan, Noorzai “has emerged as one of the most important players in the Taliban movement so far,” with deep influence over the Supreme Leader, himself a Noorzai clansman.

“Noorzai seems to be the interlocutor with the West and Middle East on behalf of the regime, and at the same time he is fast expanding his investment and joint ventures with foreign companies,” Noorani said. “The mining sector is certainly one of his favourite sectors for making profit.”

In Noorzai, Trump may meet his deal-making match. Noorzai is not a man who gives without taking. In the battle for the future, he knows exactly what his country, and his cut, are worth.