The Taliban recently shut down the internet across Afghanistan, plunging the country into a dark and frightening silence reminiscent of North Korea: no phones, TV, banks, trade, or flights in or out.

The blackout, attributed to the reclusive supreme leader Haibatullah Arkhundzada, illuminated the anger of ordinary people towards their rulers, and the widening fissures within the regime itself.

For two days, Afghanistan vanished from the world. Arkhundzada’s decree cutting fibre optic connectivity was ostensibly intended to curb young men’s access to pornography on their smart phones in a country where women are confined indoors.

Instead, the move plunged the nation into isolation. Netblocks, a monitoring site, reported a 48-hour shutdown on September 29 following months of provincial blackouts and digital curfews as the Taliban claimed to be “combatting vice and immorality”.

It was a reminder of Afghanistan’s instability and the threat the Taliban poses to security both domestically and beyond the country’s borders. The end of 40 years of war in 2021 segued into state capture by a group that nurtures jihadism while perpetually teetering on the edge of violence.

The blackout also fuelled speculation about broader surveillance implications as intermittent outages continued in some parts of the country. Netblocks said on October 8 “Instagram, Facebook and Snapchat are now restricted on multiple providers”.

Afghan and foreign sources have said senior Taliban leaders were unaware of the decree until it happened, a hint of disunity among a group that has assiduously presented a monolithic front. The subsequent pushback, from members of the cabinet and the powerful business community, had for the first time forced Arkhundzada into reverse. The order was rescinded after two days.

“It was a rare crack in alignment,” said a western diplomatic source. “There are cabinet members in Kabul who do see that there needs to be some softening up on some issues, like the treatment of women.”

In contrast to Arkhundzada’s isolation, he said, many Taliban figures, especially those with provincial constituencies, were dealing with the consequences of his decrees.

Dozens of unilateral orders have banned music, photography, toys, and television images; women have been erased from public life and even told they need only one eye.

The diplomat said women were dying unnecessarily for lack of medical treatment, unable to seek treatment from male doctors though women were shut out of higher education – a tragic result of Haibatullah’s “total isolation from that reality” that nevertheless leads to intense pressure on leaders at lower levels.

“That’s not about policy differences, it’s something far more fundamental,” he said.

Senior leaders of the movement and the Kabul bazaar had tried “to bring him up to speed,” the source said, after they were forced to relay messages to each other “on pieces of paper carried by guys on motorbikes”.

The internet ban also tore the muzzle off a population silenced by four years of repression that has included censorship of once-free media and prison for protestors.

In the absence of trustworthy information beyond Taliban propaganda, residents put two and two together and got five. Rumours of a coup – even that the American military had returned – began circulating immediately.

As elsewhere – Iran, Myanmar, Russia – blocking the internet did not silence communication; it merely enabled distortion and lies to flourish. Afghanistan became a nation talking to itself in the dark, with no one able to distinguish fact from fiction.

Much of the rumour-mongering seemed to reflect the wishful thinking of a population that is exhausted, humiliated, and desperate for change. As several people, contacted in Kabul and Kandahar when connectivity was restored said, anything would be better than this. “There’s a powerful demand for a change,” said a Kabul resident, the head of a charity who requested anonymity.

One of the rumours that swirled during the blackout days was the supposed demotion of Haibatullah’s main rival for the leadership, interior minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, the man many within the movement see as the future Emir.

Theories about Haqqani’s ambition for the leadership have circulated since the Taliban’s return. There are indications he has Washington’s implicit backing – a sympathetic piece in The New York Times a year ago that called him Afghanistan’s “best hope”.

An Afghan political source close to his Kabul faction said Haqqani had been counselled by American government representatives during a recent self-imposed exile in the Gulf, to “be patient,” in a clear warning not to take the supreme leader’s title by force.

Suggested Reading

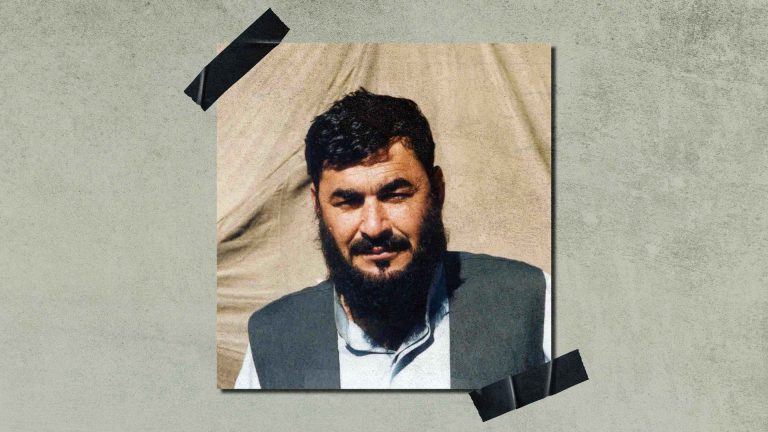

Bashir Noorzai, the Taliban’s godfather

In the meantime, international consensus favours the status quo, even if that means horrible repression. That gives Akhundzada carte blanche to take Afghanistan “backwards, not just 100 years, but 1,000 years,” the diplomat said.

The kind analysis behind the blackout is that Arkhundzada, who is billed as an unworldly religious scholar, had no idea that cutting the fibre would also kill everything else. The less kind — and perhaps more plausible — explanation is that the move aimed to facilitate broader control over access to information, in line with policies of neighbouring countries that largely support the Taliban’s draconian rule.

The blackout underscored the convergence of the Taliban’s worldview with that of its regional patrons. In China, the ruling Communist Party’s “Great Firewall” polices dissent and filters ideology; in Iran, the Supreme Council of Cyberspace exerts an ever-tightening grip on access to the global web. In Pakistan, selective bans on social media routinely silence political opponents; while Moscow has fused censorship with surveillance to suppress anti-war voices.

Each of these governments has cultivated ties with the Taliban since the Taliban took over, sharing both an interest in curbing western influence and a model of digitally-enforced obedience. Russia is so far the only country to legitimise Taliban rule with recognition; the others are among dozens with “ambassadors” based in Kabul.

China, Pakistan, Iran, and Russia all worked behind the scenes throughout the 20-year war to support the Taliban’s victory and the expulsion of the United States and its allies. With the Americans went billions of dollars in reforms that included health, education and media.

But now, as the rumours around Haqqani, of coups, and of a possible US return suggest, public tolerance of the Taliban is wearing thin. The group’s inability to provide competent governance – jobs, shelter, food, and emergency aid for frequent natural disasters – has led to widespread discontent that has intensified since the internet blockage.

Millions of people rely on contact with the outside world for funds sent by relatives. Those millions in the diaspora, who could not contact family and friends, loudly criticised the Taliban and its supporters for abusing the rights of the population.

Daoud Naji, who heads the political committee of the anti-Taliban Afghanistan Freedom Front, said there was debate within the Taliban leadership about “the issue of internet use,” indicating a nascent dissatisfaction with the current leadership.

“Although a complete shutdown caused significant disruptions to their daily operations, forcing them to restore access, the idea of restricting internet use for ordinary people still persists,” he said.

“The violation of Haibatullah’s decree by authorities in Kabul remains unacceptable to some members of the Taliban, fuelling a serious but silent internal dispute within the group,” Naji said.

During their long years in exile, the Taliban learned the value of communication and the power of propaganda. But the short-lived blackout brought a lesson of its own: in a region where power depends on silence, shutting people up is easy; keeping them quiet is the hard part.