Somewhere in an alternate universe, Britain is currently the most important country in Europe.

10 years on from the Brexit referendum, now’s a good time to take stock of where Britain stands on a world stage that has become both less predictable and more dangerous.

A good starting point for understanding exactly where exiting the European Union has left us is to consider the counterfactual – what Britain’s role in the world would be, were we still inside the EU.

The most obvious disruption to the entire continent since 2016 has been Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It has asked difficult questions about Europe’s ability to end itself at a time the continent has become estranged from its most important security partner, the United States. For many diplomats and officials, Vladimir Putin’s expansionist aggression has woken Europe from its security slumber and underscored exactly how vulnerable decades of piecemeal defence spending and complacency – the comfortable assumptions that aggressors like Russia and Iran would never attack us, and that even if they did, America has our back.

“These days the EU is necessarily playing a much greater role in security,” Robert Pszczel, a former Nato official and Polish diplomat. “Not just in terms of financing, but also laying the groundwork for the EU carrying out operational tasks.”

Pszczel says that if Britain were still in the EU, its “wise counsel would be valued” by allies like Poland, the Baltic states, Finland and Poland, as our battle experience and larger defence budget would help frontier states and hawkish countries push back against unrealistic or bad ideas from other member states – and the EU institutions themselves.

“Some of those ideas imply almost burying Nato today- let’s develop EU collective defence mandate now, establish EU military commands duplicating Nato structures or creating a European army,” he says. “Such a formation does not exist even within Nato. Governments will not relinquish their constitutional duties. Britain would help push back against silly ideas.”

Had Brexit not happened, the modern politics of Europe and the wider world would have left London as potentially the most important capital on the continent. While talk of a Eurosceptic tidal wave crashing across Europe is often overstated, there has been an undeniable drift across the bloc where now, many member states share the standoffish view of Brussels that Britain had during its time as a member state.

“It’s not a question in my mind,” says a senior European diplomat. “Britain would be having a major moment.

“ Lots of member states previously shared the UK’s sceptical view of ever-closer union and Brussels overreach. They were able to hide behind Britain as it stood up for national sovereignty within the EU. I have no doubt, when you look at the politics of Europe as it currently is, that trend would have continued and Britain would have lots of allies who would support its agenda for the whole of the EU.”

This view is common among diplomats and officials. If you look at virtually any of the main issues Europe faces in 2026, the British position is more or less the norm: support for Ukraine; standing up to Russia; immigration; protectionism on trade; a changed approach to the green agenda. Multiple officials also pointed to Britain’s unique relationship with America and the ability of leaders to win over Donald Trump and limit the damage of some of his bigger tantrums.

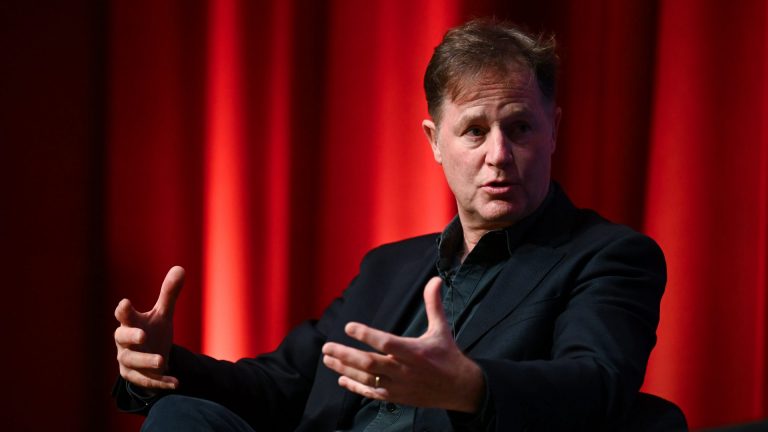

Suggested Reading

I agree with Nick Clegg (and that’s the real Brexit problem)

If a leading role in Europe that could be leveraged on the world stage is what we could have won, what have we lost? How have things changed for us and what has become of Global Britain?

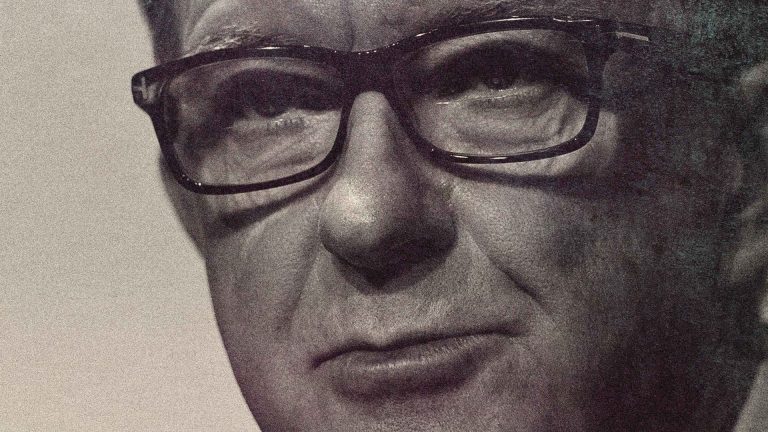

Nigel Sheinwald, an experienced diplomat who has served as the UK’s ambassador to both the US and the EU, sees the timing of leaving the EU as particularly unfortunate, given what has happened geopolitically since 2016.

“Brexit was bound to reduce the UK’s impact because it severely weakened our role in our home region. But the problem was made much worse by the timing – as we entered Trumpworld in which America’s traditional alliances have been downgraded, and as the international landscape has become more divided and geopolitical,” he says. “The UK is unanchored and weaker economically and so struggles to make its undoubted assets (diplomacy, security, intelligence) count.”

Of course, the UK has not become an irrelevance, far from it. We are still a nuclear power with a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. We are still a G7 country and an important economic partner that other countries seek to trade with, invest in and work alongside on key issues.

“On European security, a post-Brexit UK can reasonably claim it has played a leadership role – its support for Ukraine in the early stages of the war galvanised other governments: it set the pace by sending tanks and longer-range missiles to Ukraine sooner than other allies,” says Chatham House’s Olivia O’Sullivan. She does, however, caveat this by saying “there’s no real argument that EU membership would have been a barrier to doing this if the UK had stayed in.”

One area where the UK has become undeniably weaker because of Brexit is economically. The economic downsides of Brexit are well known – and have consequences beyond making British people poorer.

“A prosperous country is more secure and more able to fund defence, diplomacy, and aid. But also, because the UK left a larger trade bloc just as global trade has become more volatile and weaponised,” says O’Sullivan. “Although no country or bloc has a perfect way to respond to either Trump’s tariffs or the pervasive threat of economic coercion from Chinese supply chain dominance, the EU has the economic heft to at least in theory respond in kind.”

The China question has unquestionably become more complicated for Britain since leaving the EU. America has become more volatile and protectionist on trade as we have erected barriers between us and our closest neighbours. The trade deals signed with other countries do not, by any economist’s calculation, make up for the hit to GDP we’ve suffered as a consequence of Brexit.

China, a country we now recognise as a problematic security risk, is now seen by many as a necessity if Britain is to avoid getting squashed between America and the EU, with whom increasing or restoring our trade relationships comes with political complications of our own making.

Chinese president Xi Jinping is aware of this and is willing to exploit what it sees as a perceived weakness. “Beijing wants to get the UK (and/or the EU) not to side with the USA. But it sees London as the softer underbelly, as the UK is more receptive to Chinese investments and partnerships,” says Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute.

Many have tried, but it is hard to make any credible case that the UK has become a stronger nation and more assertive on the world stage since leaving the EU. Even the claimed benefits, like leading efforts for Ukraine or speedy vaccine rollouts, are easily fact-checked and debunked after five minutes on Google.

It is likely that Britain will at some point reopen the European question. That is another article for another time. But 10 years later, it is now reasonable to take stock of our decision to leave the EU and ask not only what we have really got from it, but also how likely we are to see any benefits from it in the next 10 years.

Emmy award-winning journalist Luke McGee is on Substack at lukemcgee.substack.com