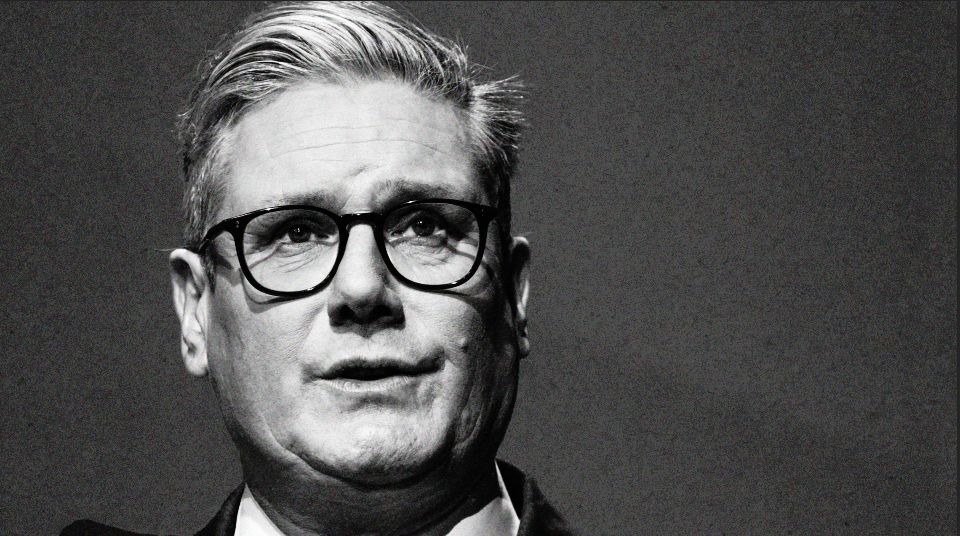

Remember the Brexit reset? What was once a key pillar of Keir Starmer’s platform for government – and a target for cries of “betrayal” from Brexiteers – barely gets a mention these days.

Back in May, the prime minister cleaned up some of the mess left by the previous Tory government from their attempts to settle Brexit. Removing trade barriers and collaborating on mutual concerns, such as migration and defence, was a good first step for Starmer.

But even with his dismal poll numbers – in stark contrast to those of Mr Brexit himself, Nigel Farage – the PM still has the political space to push for an even closer relationship with Brussels.

The risk of a backlash from Brexit voters seems significantly diminished nearly a decade on from the vote, where rampant Euroscepticism is now a minority view held by a group of people who would probably never vote for Starmer, anyway. Poll after poll shows a range of views on Brexit, the vast majority of which are somewhere on the spectrum of regretting the vote and wanting closer ties, all the way to full-blown rejoining of the bloc.

With limited domestic blowback, now would be a good time for Starmer to start thinking about phase two of his reset, because he would find himself knocking at an open door in Brussels. The mention of Britain is no longer met with an eye roll or pained wince by EU officials.

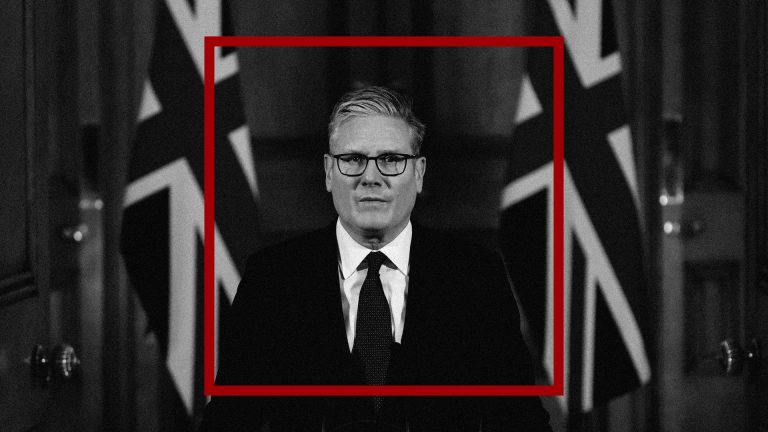

“You probably have the most Anglophile president in her [Ursula von Der Leyen] that there’s been for years, even pre-Brexit,” a senior Commission official told me last week over coffee. Sitting opposite the Commission’s enormous HQ building in the centre of Brussels, the official said that “the way we see it, Britain has finally moved on and is ready to work with us. We want that, and in some areas, I think we accept we need that.”

This gentler tone towards the UK was echoed by several officials working across multiple institutions and member states. “It feels like Britain has hit a bit of a reset itself and moved on from all that,” said an influential diplomat. “All of that baggage from the previous government, I think an election has cleared it out a bit,” they said.

Another diplomat agreed, adding that “lots of the people in this town who were driven mad by the Brexit years have moved to new jobs or left Brussels altogether. There isn’t the same level of PTSD that there was even one year ago.”

This might be purely anecdotal, but in the past few months, EU officials have responded to questions regarding Britain and the partnership with considerably less snark than they had before. “I think the agreements made in May helped a lot as they allowed us to take that first step forward into something new, rather than obsessing over the past or assuming that we were as interested in Westminster politics as you lot,” said one of the diplomats.

Suggested Reading

Smash the populists, Keir

The new UK/EU relationship isn’t just confined to warm words. European officials have long believed that the continent faces multiple crises that would be much easier to deal with if Britain were on the same page.

The big one is security. “We have realised eight months in that the American cavalry isn’t coming to help us,” a European security official told me. This particular quote was in reference to the mixed messaging that has come from the White House since Trump’s return to office on how he views the war in Ukraine.

The official continued: “It is pretty clear that America on the whole doesn’t share the values of most Europeans. That has probably been true for a long time, but it’s more clear now than ever.” They went on to explain that on issues like climate change or the battle to lead on AI, America, in their opinion, sees Europe as a competitor that is to be defeated.

They explained that this dynamic could extend to how America might decide to share intelligence in the context of counter terrorism or fight disinformation that leads to anti-Western radicalism online. “I do not think this will change even if a Democrat wins next time. I think this is what America is now,” they said.

This is where Britain’s decision to chum up to Europe or not gets a lot more serious. Whether or not you believe that a great civilisational clash is upon us, the transatlantic alliance has undeniably changed in the past two decades. It is highly likely that, sooner rather than later, leaders will need to make choices that could have implications for generations.

What happens, to use just one example, when European countries realise that in order to meet their own targets for electric vehicle ownership, they are faced with three choices: buy European, buy American, buy Chinese?

Option one requires massive investment and pan-European cooperation (always tricky) and will probably result in the most expensive product. Options two and three will be cheaper, but come with the risks of geopolitical volatility and diplomatic baggage.

This dilemma applies across a range of future issues, from AI to national security, and will be particularly acute for Britain, not in any of the big three camps.

The good news is that Europe broadly wants Britain in its camp and is willing to have us in its camp on relatively favourable terms.

Starmer could start to make progress now on decisions that will make all of this a hell of a lot easier further down the line. Even if Farage does end up in Downing Street, Europeans are confident that his focus will be so heavily on domestic issues that he is unlikely to undo any agreements he inherits, especially if they have proven to be successful in the time before he takes office.

At worst, making overtures to Europe now would upset a bunch of people who are already pretty down on Starmer. At best, he could make decisions that give Britain better options later down the line.

And who knows, he might even win over some centrist voters tempted by the Lib Dems in the process.

Luke McGee is an Emmy-award-winning journalist, broadcaster and writer