I don’t mean to alarm you, but if you hadn’t heard, the world record for the most liked Instagram post by a woman has just been broken.

It amassed more than 14m likes in the first hour, 1m reposts in less than six, and dominated front pages and breaking news alerts across the globe. The following day, as the US president gave a press conference on serious matters of war, he was asked about it. And he answered with as much sincerity as Donald Trump could be expected to muster.

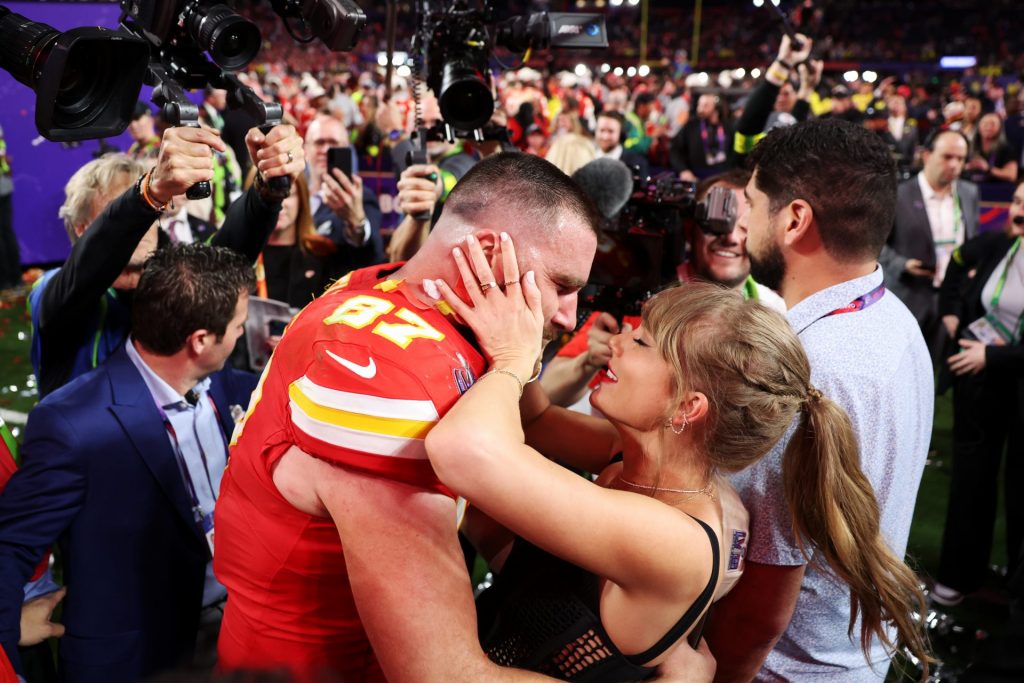

I am of course talking about the earth-shattering news that Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce are getting married. The world record-breaking Instagram post featured the happy couple plus a ginormous ring and the caption: “Your English teacher and your gym teacher are getting married” .

This sentiment tells you everything you need to know about Swift’s relationship with her fans. Just as many schoolgirls believed that their teachers genuinely thought about them as much as vice versa (guilty as charged), Swifties have reacted to the news with more excitement than I imagine some will have for their own weddings. This sort of parasocial relationship is not new in the music industry – one only need look at Beatlemania or the craze over One Direction. However, Swifties’ utter devotion to not just her music, but her life, her aesthetics, her stats – just her, really – is singular in not only scale, but in how Swift manages to utilise obsession to her advantage. Anything she releases, no matter how facile, how insignificant, will be devoured en masse. And she knows it. And it’s how she is changing the music industry altogether. Somehow Swift has managed to pull off the feat of being, simultaneously, everywoman, the girl next door and a relentless, money-making capitalist machine.

Her upcoming album, The Life of a Showgirl, announced weeks before her engagement and, coincidentally, first launched on a podcast alongside Kelce and his brother, is her third album in as many years, and her 12th in total. Well, that is if you don’t count the re-recordings of four of her previous albums, which were released from 2021 onwards so that Swift could own all of her music (these albums were sold to an investment fund by her then manager, before being bought back by Swift this year). I do not doubt that her intention was originally to own her own music. But one does start to become cynical when most of these “Taylor’s Version” albums also had “deluxe” versions with bonus tracks or acoustic versions, that fans were also encouraged, nay, expected, to purchase.

If these weren’t enough to elicit accusations of a cash grab, her most recent album, The Tortured Poets Department, pointed firmly in that direction. Because even though fans had become used to Swift’s elaborate release cycles, this was the most excessive iteration yet. The album launched with a standard edition, four deluxe editions, and a digital double album. Tally this with the individual colour/album cover variants, and the bonus digital versions, and the remixes, and there are 36 different versions of this album. The Daily Mail even ran a story at the time, “Taylor Swift sparks backlash by dropping 15 MORE tracks just two hours after superfans shelled out on multiple versions of her new album The Tortured Poets Department”.

To be fair to Swift, her obsessive fans literally buy into her uber-monetising strategy. They hang on her every word, every outfit she wears on her tour and the exact time she posts things, because they know the pop star loves to leave Easter eggs to build anticipation. It’s a literal chicken and egg situation: she gives them constant content, music, information about her love life, outfit combinations for them to feed off, turning them into junkies searching for their next score of Taylor. Now, with The Life of a Showgirl, she’s back again – not to say something new, but to stay constantly present.

In August, Swift’s ever-churning marketing machine, Taylor Nation, dropped a dozen glossy shots of her in orange Eras Tour outfits before plastering her site with another orange countdown clock set to expire at 12:12am. The moment it hit zero, the site revealed a sales page for the album in three “collector” formats – vinyl, cassette, and CD. Since then, more countdowns have popped up, each leading to the exact same album dressed up in different colours. No one has heard a single song from this album, yet her fans stood poised for the countdown to end with credit card in hand.

The relevance of the album being orange is that each of Swift’s eras has a colour, an aesthetic shorthand for fans. The only one left unused was orange, so many assumed this album would take it. Instead, the cover was teal, showing Swift in a bathtub in homage to Ophelia. So as to never upset her fans, Swift promptly released several alternative (orange) album covers, ostensibly for fans to pick which ones they liked best. This has also been done by Sabrina Carpenter, whose recent album, Man’s Best Friend, had a cover depicting her being pulled by her hair and led like a dog, by a man. Not very feminist. This caused a massive uproar, and so she released several alternative covers, in which she appears to be portraying Marilyn Monroe. This idea of multiple album covers, to be wheeled out when people don’t like the first one, ruins the very idea of an album cover. For most of modern music history your one choice had to be good. And if it was, it became a timeless piece of art in and of itself: Abbey Road, Aladdin Sane, Dark Side of the Moon. Now you get as many bites of the apple to either appease fans or sell more variants – and the artistic impetus dies with it.

Suggested Reading

The Taylor Swift scandal is not a scandal

Swift’s two-year-long tour, The Eras Tour, shattered records as the highest-grossing concert tour in history, hauling in over $1bn across hundreds of sold-out stadium shows worldwide, with millions more from merchandise and a blockbuster concert film. The Eras Tour amplified this logic. Each night offered its own surprise songs, outfit swaps, limited-edition merchandise, and viral moments – from the shows following her breakups to the nights Travis Kelce first appeared in the crowd. It was a collectible experience, designed so nothing could be missed and everything had to be consumed.

The Eras Tour embodied and added to a changing concert culture. Concerts have become Veblen goods – luxuries whose desirability increases with their price and exclusivity. Like skydiving or a trip to the Maldives, they’re something to be documented, uploaded, and consumed – not just attended.

Social media has turned experiences into performances. I have friends who feel a night out has been a waste if they didn’t get a nice picture of themselves to post afterwards. “Day in the life” vlogs showcase meals plated for the camera and outfits chosen for TikTok, not comfort. Concerts, too, are less about the music and more about the proof: the perfect fireworks shot, the glowing wristband, the outfit you wore. The performance is only half the point; the other half is showing you were there. Look only at the fervour around Coldplay and Oasis concerts. I remember my Oasis-obsessed mum, crestfallen and bitter after I failed to secure her tickets to Heaton Park, looking at videos and pictures of the concerts after. “But they don’t even like Oasis… why spend all the money?” she asked, and I had to explain that it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter that you only know three songs, the pomp and circumstance of putting on what is basically a costume, and getting to tick it off the ever-changing social media/social capital bucket list, is the point.

That’s not the only way social media is changing the music landscape. Today’s hits often blow up not because they’re heard on the radio, but because 15 seconds of them happen to get turned into a song in the background of the latest trend: a compilation of your recent holiday, a lipsync to prove how over your ex you are, a song to play over your “fit check”. Long intros, experimental structures, complex lyrics? They don’t trend, so they don’t work. The system discourages them. It is why so few non-pop or rap artists dominate the charts, and why indie rock bands struggle to get a penny of funding in today’s music industry.

To her credit, Swift doesn’t make TikTok music. But more than anyone else she thrives in this kind of attention economy, where your social media presence and what you outwardly consume is more central to your personality than any inner substance. Her fans don’t just listen to albums, they adopt them as identities. You’re not just someone who likes 1989, you’re a 1989 (Taylor’s Version) girlie. Your phone wallpaper, your outfit, your persona all reflect that. The music becomes secondary to the aesthetic.

But in a time where so many young people face loneliness and feel without purpose, can’t the community and sense of self offered by diving headfirst into the Swiftieverse be a good thing? Courtney Love famously said that Taylor Swift’s music is neither interesting nor important, but it does provide a space for women and girls to have fun and be themselves. I agree. I also can’t criticise her too much, lest I become a hypocrite and break my belief that there’s always something suspicious about the man who hates Taylor Swift (too often, it’s a misogynist in disguise). And, despite her billions and her eye-watering carbon footprint, I will admit she is very good at being an everywoman. Whatever heartbreak you’ve gone through, she’s been through too. Though hers is with Tom Hiddleston and Harry Styles, not Dave from Accounts.

None of this is unique to Taylor Swift, but she has perfected the model. Sabrina Carpenter, Charli XCX, and others are now adopting the same template: yearly releases, deluxe editions, remix drops, “collectible” covers. More versions, more content, more engagement. But more of what, exactly? More product, certainly. More revenue, absolutely. Yet less of the practice of making art that once defined pop culture. Swift is not just emblematic of how music is now marketed, she embodies what music now is.