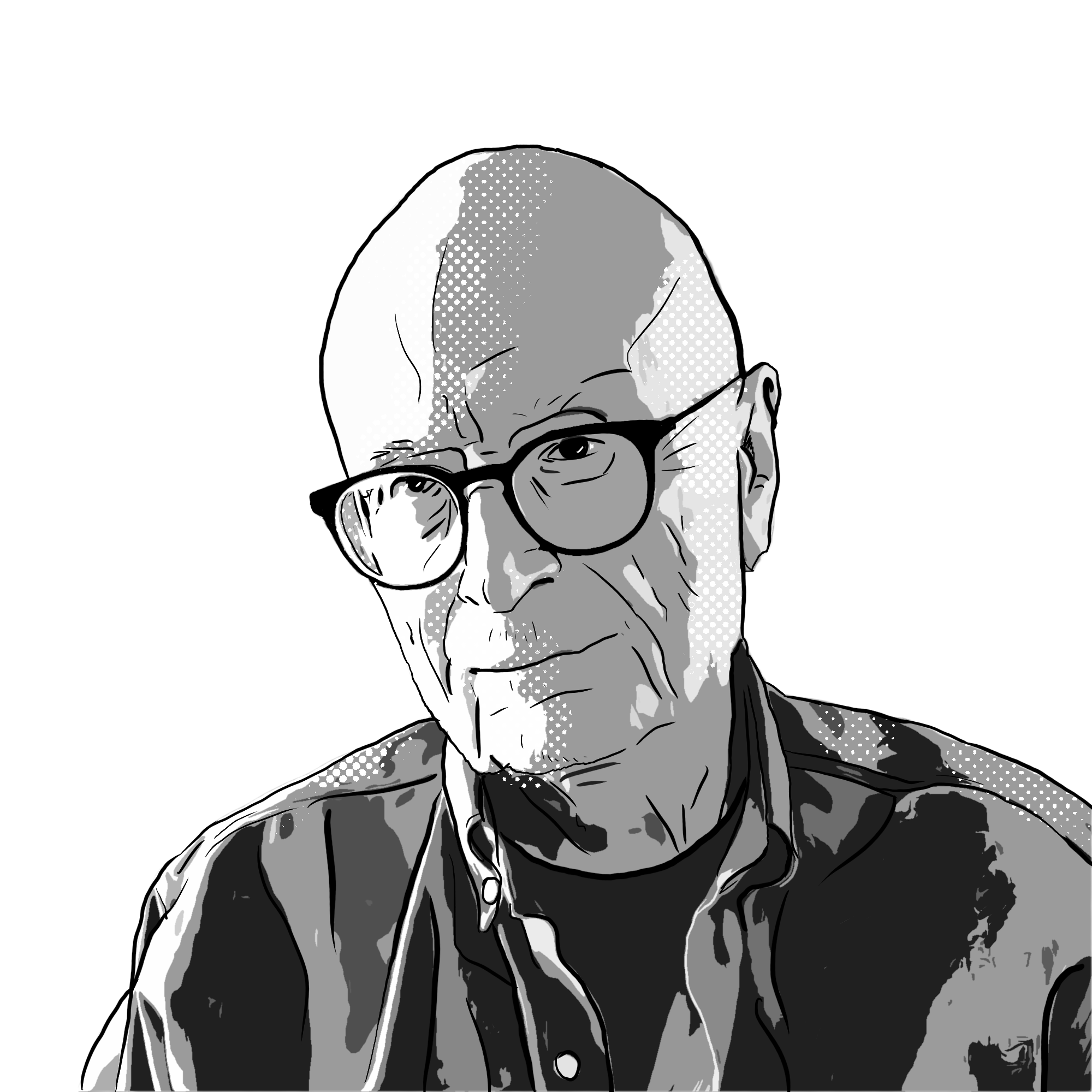

In a turn of events that has surprised absolutely no one, the Reform candidate for Gorton and Denton, Matt Goodwin, has managed to offend people.

Recently unearthed footage from November 2024 shows Goodwin mansplaining about where women are going wrong. “Many women in Britain are having children much too late in life,” he said, adding, “we need to also explain to young girls and women the biological reality of this crisis.”

This patronising guff has sparked a considerable backlash. Natalie Fleet, MP for Bolsover, who became pregnant at 15, compared his comments to The Handmaid’s Tale. Goodwin’s suggestion that women who have two or more children should be taxed less has also drawn comparisons to the policies of the Nazi regime, which awarded medals to women who had large numbers of children.

Goodwin’s comments also ignore entirely the role of men in producing children. He might, for example, consider this comment from Samantha, 32, who put it bluntly: “For people like me who aren’t desperate to have kids, we now have a choice. I would only want to have a child with a man who adds to my life and who I believe would share the responsibility. But I still don’t think that’s how it is. Among married friends, I don’t see equal weighting for some of them.

“I don’t see why I should sacrifice myself and my life and objectives unless the person I’m doing it with is going to do the same. Men say they want to be fathers but don’t understand that they need to get their shit together for us to want to have kids with them.”

It is, of course, not the first time right wing groups have seized on falling birth rates. The “Tradwife” movement – a hyper-romanticised vision of domesticity in which women stay at home, beatifically raising a small football team of children and baking sourdough – has developed a particular hold over MAGA-adjacent corners of the internet. Endless accounts, often AI-generated, often suspiciously bot-like, pump out images of impossibly serene, linen clad motherhood.

Falling birth rates are a darling topic of the alt-right, though it might depend on which falling birth rates. They may not be overjoyed to hear that births to non-white ethnic groups in the UK remain proportionally higher than to white British groups.

The subject is frequently deployed as a dog whistle by white nationalists pushing the so-called “Great Replacement” theory, that native white populations are being deliberately “replaced” through immigration.

Still, while birth rates may be weaponised by politicians and influencers nostalgic for the 1950s, the issue itself is real, and one that governments across the world are actively trying to address.

Birth rates in England and Wales have fallen to record lows, with the total fertility rate dropping to about 1.41 children per woman in 2024 – well below the 2.1 needed to maintain the population without migration, according to the ONS.

In France, the government recently wrote to 29-year-olds urging them to reproduce. In Japan and South Korea – both facing some of the lowest fertility rates in the world – billions have been poured into encouraging schemes, including lump-sum birth allowances of around ¥500,000 (about £2,400).

What Goodwin says is not entirely inaccurate: men and women in the UK are indeed having children later, and in some cases not at all. But to suggest this is because women are somehow deluded about their own fertility is not only insulting to a generation of women who are routinely reminded – at GP appointments, via targeted ads for egg freezing on the London Underground, and in uncomfortable Christmas dinner table commentary – that their biological clock is ticking. It also ignores the far more obvious socioeconomic pressures that are shaping their decisions.

The sharpest declines are among women in their 20s, and projections suggest many young women today will have just one child by 35, as the average age of first-time motherhood rises to around 31, and fatherhood to 35.

Suggested Reading

Britain doesn’t have enough children

So why are millennials and Gen Zers having fewer kids, later? On the surface, it seems pretty obvious. Only around 39% of people aged 25-34 in the UK own their own home, down sharply from about 59% in 2000. People are leaving university with an average student loan debt of around £53,000. And full-time nursery care costs can average roughly £239 per week for a child under two.

When jobs are lacking, rent is climbing, and the cost of simply existing is so high, the neat and traditional milestones of adulthood look far less attainable than they did for previous generations.

Bradley, 22, is firmly in the camp of never wanting children. “I’ve given up any hopes of owning a house, as many my age have, and think that whatever disposable income I do eventually have, I would much prefer to spend on living a fulfilling life rather than creating another one.”

But is it only economic reality that is stifling birth rates? After all, some of the countries with the lowest fertility, such as Sweden and Japan, rank highly for quality of life and economic performance.

Bradley’s opposition to fatherhood is also shaped by a broader disillusionment with the state of the modern world. “Initially my opposition to having children was moral – based on the huge climate impact of putting another person into the world and the question of whether putting a kid into such an awful world is a kind thing for them.”

He adds another, more uncomfortable layer: “I would find it really hard to raise a son. I would struggle to reconcile my dislike for them – in their inevitable awful teenage boy phase – with my role as their father. I would genuinely reconsider my opposition to having kids if I could guarantee it was a girl.”

He is not alone in bringing gender anxieties into the conversation. Many people blame “ambitious”, degree-collecting, flat-renting women who have apparently been duped by liberal modernity into delaying motherhood, thereby fuelling both plummeting birth rates and the so-called male loneliness epidemic (a line of argument frequently aired by figures such as Jordan Peterson).

But what about men’s role in baby making? Why is no-one blaming them? Columnist Stella Tsantekidou posted on X: “Please stop lecturing women. The world is overflowing with beautiful, successful single women of reproductive age begging for a normal man to come along, and most have been looking since they were 20, frankly.

“Tell men to get over their alcohol and drug addictions, to commit to one woman and not waste their time, learn how to ask questions and take an interest in women as humans, basic standards of taking care of themselves, manners, get over their anger management issues etc.”

Some may call that “strident”, but it is a frustration shared among women in their late 20s and early 30s who feel the pressure to have children intensifying while, as Samantha suggested, the pool of suitable partners feels, to them, unappealing.

In the UK, young women are now significantly more likely than young men to hold a university degree, and young men are also more likely to be NEET (not in employment, education or training). They are also considerably more likely to live with their parents into their late 20s and early 30s.

The reasons why the birth rate is falling are numerous and complex, but I err on the side of a generation that has been routinely screwed over, and then routinely blamed for it. A cohort supposedly trapped in arrested development thanks to Covid, sky-high rents and childhood bedrooms that have lingered far longer than anyone planned. A generation accused of not drinking, not dating, not having sex, when a few drinks can wipe out half a week’s disposable income.

Even for those who want the old milestones, there is no guarantee that the traditional formula of job, partner, house, baby, will fall into place, and certainly not neatly within the window of our so-called “biological reality”.

Suggested Reading

Matt Goodwin’s fall into the abyss

So if politicians are genuinely alarmed about plummeting birth rates, perhaps the solution is to tackle the housing crisis: cohabiting in a studio flat where you can see the pile of dirty dishes from the marital bed isn’t exactly a recipe for romance. Fix the graduate jobs market so young adults can imagine affording both children and a life. Make going out feel possible again, so future couples can meet under the loosened inhibitions of a few vodka and cokes.

If politicians want more babies, maybe they could start by making life feel less impossible for the people expected to have them.