People leave the places they live for all kinds of reasons – war, famine, job opportunities. Mien Boerrigter’s journey was provoked by a cheating spouse.

The daughter of a Dutch wine merchant, Mien sailed to the Chinese port of Tianjin to marry a man she barely knew. She was a strong woman who survived cholera, typhoid and the Boxer Rebellion. Her husband Thomas, a customs official and entrepreneur, was popular and rich. He was also a serial womaniser.

For years, Mien turned a blind eye but when he got one of his mistresses pregnant, it was the last straw. In 1911, she shipped her belongings to Vladivostok, grabbed her four children and jumped on to the Trans-Siberian Express.

“Back then it was unheard of for a woman to act so independently” says Ernest Feeks, Mien’s grandson, “but once she had made up her mind, nothing could stand in her way.”

An elderly man with wispy hair and wire-rimmed glasses, Ernest is standing next to the large brown suitcase which accompanied Mien on her 16-day journey via Lake Baikal to Moscow and from there on to Holland. His grandmother later became a suffragette, marching through The Hague wearing a sandwich board, demanding votes for women.

I meet Ernest on the ground floor of Rotterdam’s newest and most intriguing exhibition space. Visitors are used to being divested of their bags before entering museums, but at Fenix, the left luggage room is an art installation.

Two thousand suitcases of all shapes and sizes, as well as trunks, hat boxes and violin cases, are piled up high, creating a chest-high maze. They are all lashed together but each one has made a unique journey.

Coloured tags with QR codes allow visitors to wander through the Suitcase Labyrinth and listen to their stories. If Mien’s battered leather case is the oldest piece of luggage on display, the most recent is a Samsonite brought to the Netherlands by a Ukrainian refugee.

Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine contributed to a total of 108.4 million forcibly displaced people in 2022. It was a global record, but Fenix’s waterfront location is a reminder that people have always been on the move, says the director, Anne Kremers.

The art museum devoted to migration is spread out over two floors of a historic port warehouse, in Katendrecht, the city’s southern docks and former red-light district. Just across the water, the former Holland America Line headquarters – now a hotel – once shipped more than three million people from Rotterdam to the other side of the world. Today, the flow is reversed, and Rotterdam is home to 170 nationalities from all corners of the Earth.

Kremers takes me around the former warehouse transformed by the Chinese architect Ma Yansong, who is himself the son of a migrant. The standout feature is his Tornado: a futuristic structure which slices through the middle of the building leading to a viewing platform on the roof. It reminds me of a giant slide in a water park.

Everything is reflected in its silvery surface – the visitors, the sky above and the river below. I watch barges chug slowly past while yellow water taxis buzz around the piers and zip under bridges like mosquitoes. The constant movement and shifting reflections reinforce the idea underpinning the museum.

“Migration is timeless and universal,” says Kremers. “As long as we exist, as human beings we are on the move. It is part of who we are.”

That is not a view shared by the likes of Geert Wilders. The ultra-right politician recently toppled the Dutch government after he pulled his Party for Freedom (PVV) out of a fragile conservative coalition, lambasting his partners for going soft on asylum seekers.

Does the progressive strengthening of immigration laws worry Kremers? She says that the museum is “not political but it is urgent” since it addresses issues no society can ignore.

Even Máxima, the Queen of the Netherlands, the guest of honour at the inauguration, is a migrant from Argentina. “There is a migration story to tell in every family. That is why we collect stories from so many different people,” says Kremers.

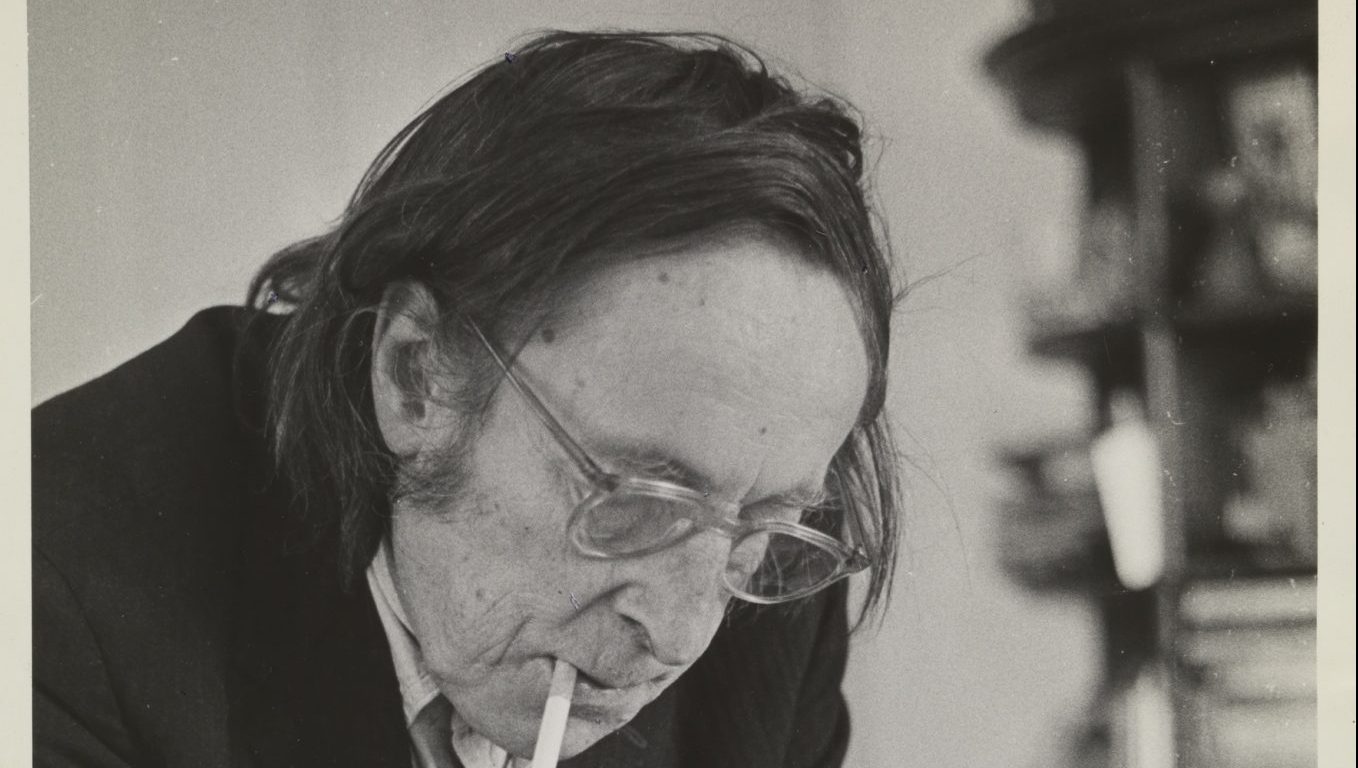

While not all the art at Fenix was created by migrants, much of it was – including Willem de Kooning’s Man in Waistcoat. De Kooning left from these very docks in 1926, hidden in the hold of a boat bound for America. Today, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century would likely be classed as an illegal alien and thrown into prison.

In an adjoining space, I meet Raquel van Haver, an artist born in Colombia. Her specially commissioned work, Luz Brilhante e Cintilante, portrays a community not from Latin America but from Cape Verde based in the Netherlands. On a research trip to the island off the west coast of Africa, she found that many people living there longed to come to Europe while those in Holland dreamed of returning home. “That desire to be somewhere else is almost like a rhythm, day and night, it’s all the same as a drum. It’s a constant heartbeat,” she says.

Her double-sided work is painted on burlap, a material that evokes Cape Verde’s role as a hub for merchant ships, but Van Haver also prizes its semi-transparent quality. “The light is always shifting. And that’s what I like as a painter, because constantly, the colours will change.”

As visitors view the work, they are enveloped by a sound loop of Cape Verdeans laughing, shouting, singing and drumming. The painting includes depictions of the Batuk dance in which women traditionally welcomed their men back after a hard day’s work in the fields. But now, says Van Haver, some guys join the dance. That’s something that would have been unthinkable in the past.

Nearby, there is another large work by the South Korean artist Chae Eun Rhee. We, In the Eye of the Wind is a double-sided triptych of six panels that contrasts sinister, beaked figures, reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch, and medieval illuminated manuscripts with astronauts and video games.

It traces a journey – from sunset to sunrise, from winter to summer. Along the way, you follow migrating birds, meet a grimy snowman with a traffic cone on his head, and a Korean migrant in Hawaii. Chae wanted to convey the sense of bewilderment and sensory overload which confronts people in new surroundings. “I wanted to show migration more as an emotional state than physical movement”, she says.

Interspersed with works by international artists, including William Kentridge, Yinka Shonibare, Cornelia Parker and Bill Viola, Fenix features real objects linked to migration. There is a chunk of the Berlin Wall and a 1923 Nansen passport issued to stateless refugees after the first world war.

The Bus, by Nashville-born artist Red Grooms, features a cosmopolitan crowd, made of brightly coloured fabric, on board a New York City bus. You can clamber on board to admire the characters, such as the Black teenager in a football shirt, the WASPy blonde with a suitcase and the Cuban in a straw hat, so long as you don’t touch.

But when you get off this celebration of American diversity, you are confronted with one bitter reminder of the refugee experience – a migrant boat seized a few years back off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa, where more than 360 people drowned just over a decade ago.

Kremers says Fenix aims to challenge assumptions by bringing hyper-reality into art. It also reminds visitors that migrants are not statistics to be kept in check but people with families and dreams just like everyone else.

Lucy Ash is a documentary-maker, journalist, broadcaster and author