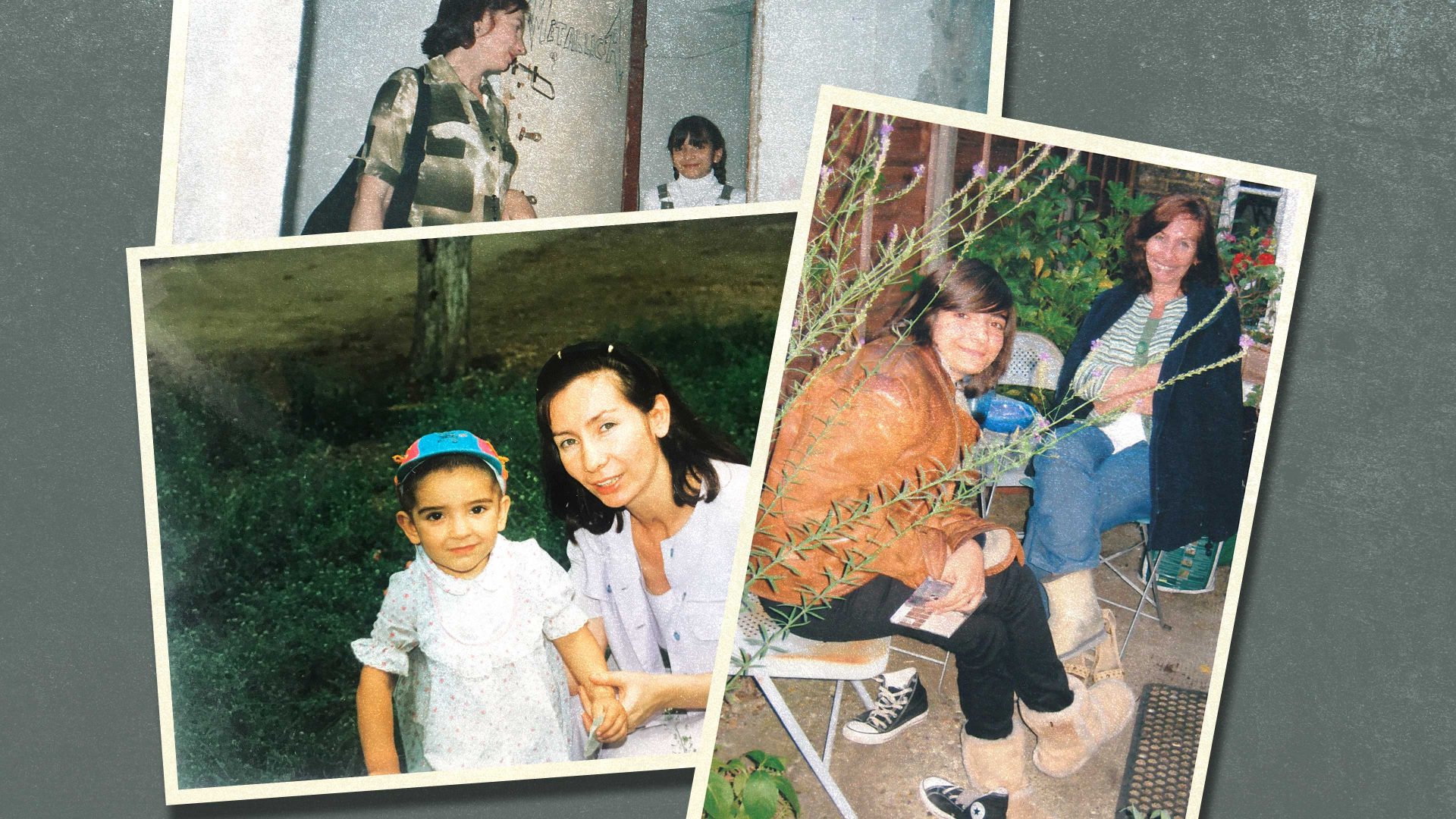

I was looking for Natalia Estemirova in a Moscow pizzeria in June 2009. I walked past her table a few times because she was sitting with her 15-year-old daughter Lana and I had expected to find her alone. The two of them were deep in conversation and didn’t seem to notice anyone – or anything – around them.

But when Natalia threw her head back and laughed at something Lana had said, I caught her eye. We had never met before, but I recognised her from her interviews on TV.

Mother and daughter had been enjoying a short summer break, staying with friends in the Russian capital before returning to their home in Chechnya. They were discussing shopping plans and a play they had seen the night before. Lana reminded me of my own teenage daughter. She rolled her eyes in the same comical way and liked the same indie rock bands.

When we met again later that week, I understood just how precious that brief holiday had been for Lana. In the Chechen capital, Grozny, everyone was pleading for Natalia’s attention. A former history teacher, she was head of the Memorial office in Grozny which investigated human rights abuses.

On the days I visited, there were queues of people outside her office waiting to tell her their terrible stories. One woman had had her house burned down because her son was suspected of joining the insurgency against the Kremlin-appointed warlord, Ramzan Kadyrov. Others clutched photographs of relatives arrested in the middle of the night who hadn’t been seen since.

Although she faced constant hostility from the authorities and operated on a shoestring, Natalia was determined to document and publicise these stories. Her office consisted of two cramped rooms, a tiny kitchen and a lavatory with a broken light. There were shelves of cardboard files, all carefully labelled with dates and names of villages and towns.

It was to this office that Lana rushed on July 15, 2009, just a few weeks after my visit. She had been trying to reach her mother for hours but there was no reply to her increasingly desperate messages. Later, the awful truth emerged. Natalia had been bundled into a car on her way to work, driven out of town and then shot five times in the chest and head.

A decade and a half later, Lana has written an extraordinarily powerful tribute to her mother, Please Live. The title refers to one of the many text messages she sent before the news came that Natalia had been killed. Her book is also a vivid account of what it is like to grow up in a war zone.

Chechnya has resisted Russian rule for centuries and in the post-Soviet era it has been scarred by two devastating wars. Fighting between Islamic separatists and Russian troops has claimed tens of thousands of lives.

During the first Chechen war, triggered by then-president Boris Yeltsin in the mid-1990s, Lana was left in the care of her grandmother in the Sverdlovsk region of Russia, nearly 3000 km away. When her mother returned to Grozny, “a painted sign at the city’s entrance greeted her with the words ‘Welcome to Hell.’”

Natalia could not bear to be parted from her only child for long, especially when two-year-old Lana shrank from her at the train station. “I turned away and cried, ‘I’m scared of this auntie!’, hiding my face in Baba’s armpit. Mum was a stranger to me,” Lana recalled. “After all those weeks she had spent away, I’d forgotten her. ‘It was the most devastating moment of my life,’ mum recalled later, ‘when you didn’t recognise me.’”

To the dismay of her grandmother, Natalia insisted on taking the toddler back to Chechnya. Sometimes Lana was sent to live with relatives, in villages and refugee camps.

When a little-known former KGB spy called Vladimir Putin became acting prime minister and unleashed the second Chechen war, Lana was taken again to her grandmother’s safe haven, a two-day train journey away. Russian troops carpet-bombed Grozny so thoroughly that the UN declared it “the most destroyed city on the planet”.

As soon as she could, Natalia reclaimed her daughter and took her back to Chechnya. But Grozny’s streets were still very dangerous, and one evening laughing soldiers sprayed the ground around them with bullets, just for fun. Ever the schoolteacher, Natalia angrily chastises them, and the “cowards” silently retreat to their base.

Despite such horrors, the book is peppered with anecdotes about Natalia’s valiant attempts to give her daughter a normal childhood. After a scary time outside a filtration camp where Russian troops often tortured prisoners, Natalia and her cameraman finally returned to Lana, waiting in the locked car. To distract her daughter, Natalia switches on the camera and encourages her to belt out the theme song from Titanic.

Suggested Reading

Putin’s tortured prisoners of war

“I watched the video for the first time several years later,” Lana writes. “I am standing in a red-and-white striped dress decorated with ribbons, singing ‘My Heart Will Go On’ by Celine Dion. I don’t know the words and don’t speak any English, so I make it up as I go along.”

On Natalia’s birthday, Lana begged her to buy a pineapple, a tall order in a bombed-out city with almost no electricity. Natalia had no time to celebrate – she had spent the day taking notes as bodies were exhumed from a mass grave near a Russian military base.

That night Lana recalls her mother’s face “had a misty sheen of sweat covering it like cling-film and it was drained of colour; it was almost the same shade as her off-white turtleneck”. Yet suddenly she snaps out of her trance and points to a plastic bag by the door containing the exotic yellow fruit. “Somehow mum made magic happen,” Lana writes.

There is however nothing sentimental about this memoir. It is searingly honest about Natalia’s priorities. Devoted to her daughter, she did whatever she could to keep her safe. At the same time, she doggedly continued her work, despite the huge risks and even after friends and associates were threatened or killed.

Lana recalls with great fondness Anna Politkovskaya, who was a close family friend. The globally renowned Novaya Gazeta journalist was shot dead in the entrance to her Moscow apartment building in 2006. Anna, like Natalia, refused to be cowed. They both often joked and dismissed “dangerous people and situations with ironic, withering comments”.

Lana could see through this bluster and her frustration with her mother pours out of her teenage diary. “I know that mum cares about me, but the job is more important to her and I’ve long accepted that,” she writes from the boarding school in the Urals. It was a miserable place where she was either cold-shouldered or branded a Chechen “terrorist” by her fellow Russian pupils. “All her life, mum worked, worked, worked, helped people and completely forgot about me… Let’s stop pretending – I get in her way. Sometimes I regret ever being born”

The self-pity and loneliness are understandable, but Natalia may have sent her daughter to the boarding school for a reason – Chechnya remains a notoriously dangerous place for girls and young women. When I first visited, the rubble had been cleared away and a gigantic mosque had sprung up surrounded by fountains which glowed bright colours at night. There were rose gardens and sushi bars and pavement cafes.

But behind the shiny new façade, it was a lawless place. I had come after spotting videos online of women being snatched from the streets by gangs of men and forced into marriage at gunpoint.

Natalia and others investigating this ‘bride stealing’ told me many of the kidnappers work for local security forces and their victims are often young, sometimes teenage schoolgirls. Back in Grozny again, Lana, aged 14, recalls a marriage proposal-cum-threat from a young Chechen called Apti. “On the bus, I looked out of the window nervously to see if I was being followed. My stomach hurt and my heart pounded in my throat,” she writes.

But many women kidnapped in Chechnya suffer a worse fate than an unwanted husband. In November 2008, within a space of two days, the bodies of seven murdered women were found in and around Grozny. Natalia took me to the place where three of the corpses were found – a desolate field on the edge of town next to a disused factory.

She suspected the killers were linked to President Kadyrov’s security apparatus. The authorities attributed the deaths to honour killings. But Natalia said women who had disgraced their families would usually be buried deep inside the forest, not left on display near busy main roads. “Somebody clearly wanted to make a point. This was meant as a warning,” she told me.

Yet Natalia remained immune to warnings herself. Kadyrov was furious with her investigations into torture and extrajudicial killings. He sought to silence her by appointing her chair of a “human rights council” but that did not stop her.

At the same time, Lana was becoming ever more aware that her mother was not a comic book heroine who could always escape, untouched. When Natalia was filmed in the Grozny market talking about her refusal to wear a headscarf, Lana was gripped by fear. “Now suddenly I saw a petite woman in a white windbreaker, a woman who had just declared insurgency on national television. How many potential enemies have seen this piece? I wondered.”

I also felt concerned for Natalia’s safety. As my colleague Nick and I gave her a lift to her home on the outskirts of Grozny, I apologised for pestering her with so many questions. She said that was her job. I wondered if Memorial supplied her with a bodyguard or at least a driver. “You must be joking,” she laughed. “I take the bus.”

I had no way of knowing at the time that I would be the last foreign journalist to see her alive.

Natalia was not a woman who thought much about self-preservation. She cared passionately about two things in life – helping other people and her daughter.

When I got the phone call about her murder three weeks later, my first thought was for Lana. Her account of her mother’s funeral is raw and painful to read. Nobody was ever prosecuted. The investigation was botched. The authorities half-heartedly blamed Natalia’s killing on a dead militant.

Three years later, when Lana returned to Chechnya on a brief visit from the UK, she channeled her grief into a clear sense of purpose. In the book, she writes of standing at her mother’s grave, and vows never to take needless risk and to ensure her own children lead “boring, stable lives far from war.” Secondly, she pledges never to succumb to bitterness nor to take life for granted.

And lastly, she promises that one day she will write a book about her mother to ensure that “she will be remembered, and her killers will fade like ghosts”.

Please Live: The Chechen wars, my mother and me by Lana Estemirova is published by John Murray